Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

It’s not in our nature to wish ill on any enterprise, so here’s hoping these businesses find a prosperous future driven by some other revenue lines.

Thanks to Covid’s Delta wave and the return of worrying case numbers, two of America’s largest laboratory companies are raking in unexpectedly large amounts of business. Expectedly, Wall Street is now anticipating impressive profit results.

Pass With Flying Dollars

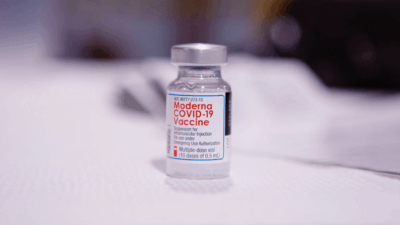

Vaccine adoption rates have thankfully lowered the number of hospitalizations and deaths in many states and countries, but the contagious Delta variant has boosted case numbers in America, necessitating a rush of new Covid tests.

As a result, Quest Diagnostics and Labcorp, two major publicly traded lab companies, are capitalizing on the situation. Questcorp is currently performing twice as many tests — 100,000 daily — as Wall Street analysts predicted, and Labcorp’s test numbers have also lapped expectations. Having sorely underestimated test figures, those analysts are now estimating lofty profits for the testing giants:

- Analysts at Baird said additional tests will create $149 million in added profit this year for Quest and $96 million for Labcorp. Quest’s stock is already up 23% in 2021 and Labcorp’s is up 34%.

- The elevated test numbers don’t even account for federally-funded testing programs for K-12 students and staff, or expanded testing from local governments, both of which Quest and Labcorp will see added revenue from.

Two-Month Bubble: While experts admit they can’t explain it, the Delta strain has driven up case numbers for roughly two months in several countries, after which case levels promptly plummeted down again. The phenomenon has happened in Britain, Indonesia, France, Thailand, and Spain. “We still are really in the cave ages in terms of understanding how viruses emerge, how they spread, how they start and stop, why they do what they do,” Michael Osterholm, a University of Minnesota epidemiologist, explained to the New York Times.