AI Market Concentration May Cause an Ethics Responsibility Shift

In a concentrated market, who’s responsible for responsible AI?

Sign up to get cutting-edge insights and deep dives into innovation and technology trends impacting CIOs and IT leaders.

With AI model development in the hands of just a few major firms and AI adoption in the hands of all, how should the tech be governed?

Following the initial AI frenzy, a few major players have cemented their place as the gold-star generative model proprietors, with Meta, Google, OpenAI and Anthropic emerging on top. The concentrated market has raised the question of who should be responsible for AI governance: the creators or the users.

“All model creation has wound up in the hands of a few dominant ones,” said Pakshi Rajan, co-founder and chief AI and product officer of Portal26. “This kind of general-purpose AI, people don’t have to build anymore.”

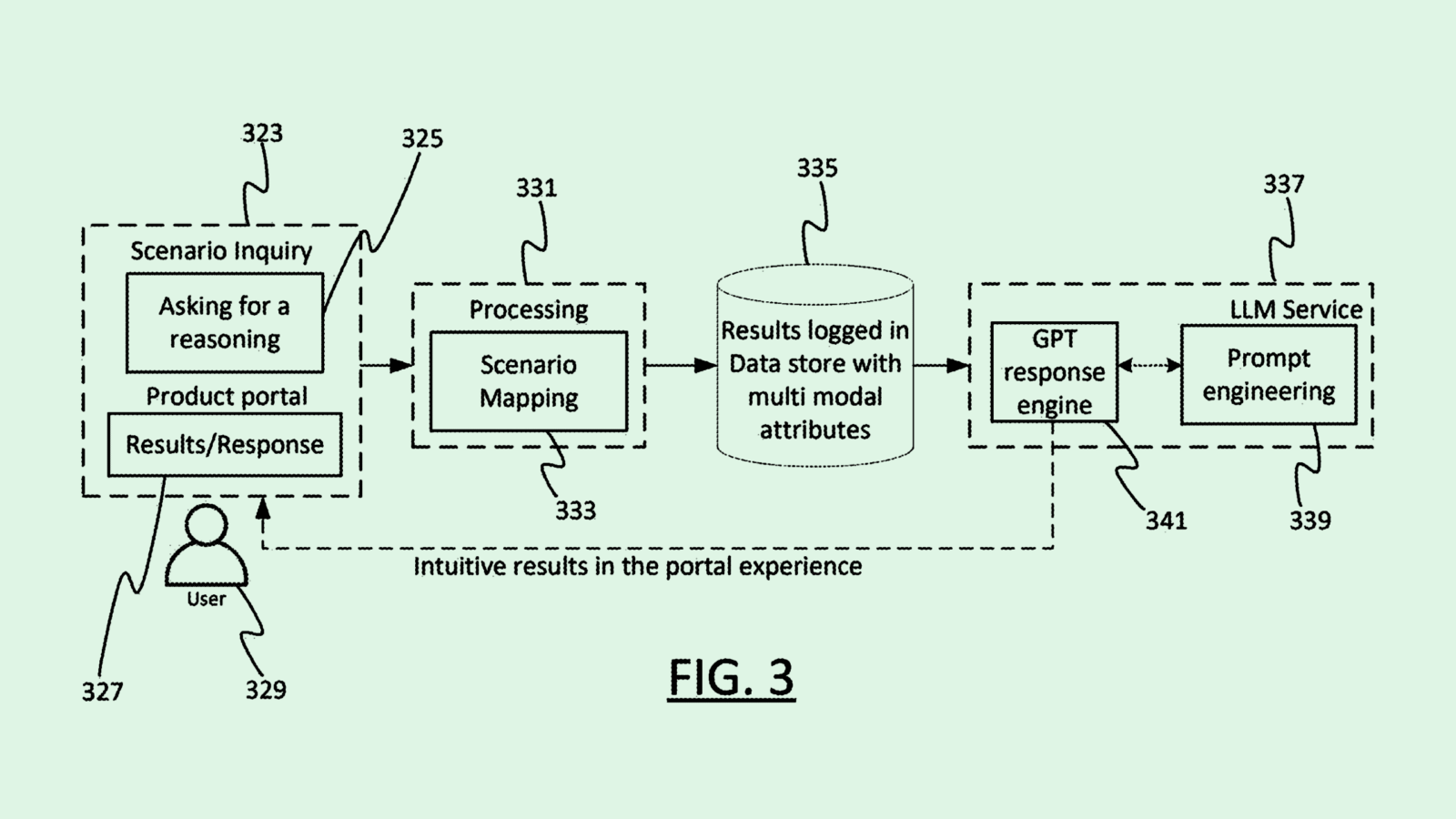

There are three main pillars of AI governance that developers often follow when building these models, Rajan said: Data, ethics, and explainability.

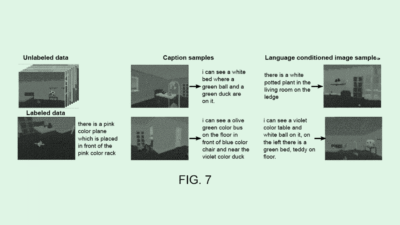

- Before building even starts, developers need to make sure their data is up to snuff. This means ensuring it’s as high-quality and free of bias as possible. Once trained, it’s important to monitor models for “overfitting” to datasets, or when a model doesn’t work on new data.

- The next pillar is ethics, Rajan said. This means asking whether or not your model is going to be used for good. “In other words, can I actually trust this model to make good judgments without causing harm to the society?” he said.

- Finally, there’s explainability, or the capability of a model to retrace its steps and show its work, Rajan said. A model being able to explain how it came up with its outputs and what data its responses are derived from is “the holy grail – and the point where some people just give up,” he said.

While the major players can try their best to follow those pillars in creating and deploying their nearly trillion-parameter generative models, such AI systems are so big and so widespread that they’re practically “neural networks on steroids,” Rajan said. Even with guardrails in place, governance is made harder by the fact that many of these models are actively learning and growing from their users.

“On the model creation side, there is governance required,” Rajan said. “They do have guardrails. But they can’t possibly put a guardrail around every document you could possibly upload.”

That has caused a shift in responsibility, with the burden of AI governance and responsibility shifting into the hands of the people interacting with the models. And despite this new responsibility, enterprises continue to move forward with AI adoption because they’re “afraid that they’re going to lose out” if they prohibit their workforces from using it, Rajan said. “Everyone has to somehow be accountable for how they’re consuming AI.”

The pillars of AI governance for the user look a bit different than those of the builder. The main goal? “Value maximization and risk minimization,” Rajan said. This means identifying where AI is of most use within your organization, and whether the risks of using it – like data security, bias or ethical issues – are significant in those use cases.

As for employers, this could mean implementing clear and understandable responsible use policies and education around AI, and applying consequences when those policies are breached, he said.

“Employees are using models, and it’s the employer’s job to govern and monitor what’s going on,” Rajan said. “Not knowing – and trusting that everyone is using AI responsibly – that phase is out.”