Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

We had the opportunity to talk to the founder and CEO of AcreTrader, Carter Malloy, to better understand the market forces shaping the agriculture industry and dissect the merits of farmland as an asset class.

Do you Know the Price of a Gallon of Milk?

As far as professions go, it would be hard to conjure up a lifestyle more ‘salt of the earth’ than farming. The very lifeblood of the economy, farmers work hard to provide for the rest of us. As anyone who has visited or worked on a farm knows, it’s incredibly demanding work.

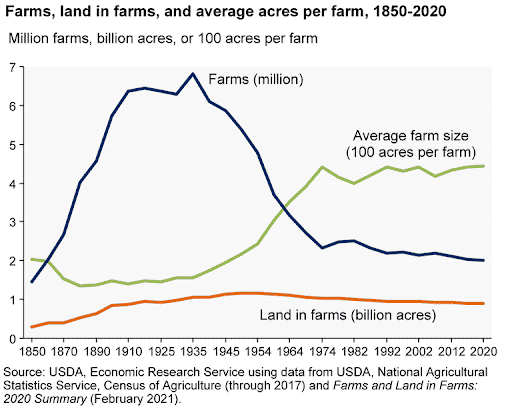

In the most recent federal survey, there were an estimated 2 million farms in the US. All told, the agriculture, food, and related industries contributed just over $1 trillion to the US economy in 2020, representing a 5% share. Farming, as a critical subset, contributed $134 billion.

But farming carries more weight in shaping the national zeitgeist than simple dollars and cents would suggest. From a geopolitical perspective, farmers are routinely caught in the crossfire of tit-for-tat trade wars and are used as bargaining chips in what we’ll call nation-state chess. Famously, soybeans became a centerpiece of the recent US-China trade war, causing exports and prices to crash and forcing the government to step in with compensation.

Similarly, farmers can be impacted just as dramatically when real war hits. After Russia invaded Ukraine, which produces a fifth of the world’s high-grade wheat, the ripple effects were felt across the globe. And from a consumer perspective, everyday citizens can feel these gyrations — as direct hits to the wallet — when checking out at the grocery store.

Planting the Seeds

So how does one analyze farmland as an asset class?

Like any other, farming is a business. Instead of widgets, farms produce commodities like corn, soybeans, barley, and oats. The price of these commodities, and the value of the farmland that makes them, are governed by the basic principles of supply and demand. Let’s go step by step.

The Demand Side is pretty straightforward. In 1900 there were 76 million people in the US. Today, there are 329 million. By 2058, the population will pass the 400 million threshold, according to the US Census Bureau. More mouths, clearly, create more demand for food. In faster-growing countries like India and China, or in Africa, surging populations raise global food demand and create cross-border demand.

The Supply Side is more nuanced. The USDA recently reported that the US lost a staggering 1.3 million acres of farmland in 2021. You might be thinking: Lost? It’s not as if land is falling off a continental shelf into the sea. But thanks to residential and commercial real estate developments and the ever-expanding suburban sprawl, approximately 2,000 acres of farmland are lost each and every day, according to the American Farmland Trust.

On the productivity side, there is little question that farming today bears little resemblance to the quaint ol’ days of Little House On The Prairie. The scythes of yesteryear have been mainly replaced by industrial-sized tractors that can make their way through acres of land in minutes, not days.

Thanks to technological developments in animal and crop genetics, chemicals, equipment, and overall farm organization, farm yields have tripled from 1948 through 2019.

But at the same time, climate experts warn that, despite overall productivity increases, harsher winters and warmer summers have crimped gains, accounting for a 20% drop in relative outputs.

Framing The Investment Story

To go a layer deeper into the farmland story, we sat down with AcreTrader CEO Carter Malloy to discuss how he and his team are approaching the current investment landscape for farmland.

TDU: What gave you the idea to launch AcreTrader?

CM: In many ways, my upbringing served as a foundation for the business — my father worked in agriculture and my mother was an entrepreneur. While I started my career working on Wall Street, I always maintained an interest in agriculture, making side investments in farmland projects with people in my network. Like many ventures, the inspiration came from initial frustrations with the status quo. I was having really solid financial outcomes and benefiting from the fact there is very little institutional participation, but everything around the edges — identifying deals, arranging financing, liquidating an investment, made me think — there has to be a more efficient way to make these investments.

As it turns out, there wasn’t.

So I started to dig into the idea of fractional investing. And that seemed to be a highly scalable business model, to bring both sides of the table together, both farmers who want to raise capital and grow their business, and individuals who want to invest in rural America. So thus the business idea was born.

TDU: Can you dig into what makes farmland such a compelling asset class to invest in?

CM: There are a couple reasons. On a fundamental level, there are the inherent supply and demand economics at play. There are mouths that need to be fed, and farms create the food to do so. Secondly, the valuation of farmland doesn’t really show correlation to any other major asset classes. For long stretches of time, we’ve seen consistent slow and steady appreciation.

However, and this is vital, we can find some correlation with CPI and PPI (Producer Price Index) where land values have risen in close lockstep with inflation over time. I think a lot of smart people view farmland as a gold-like asset with the added benefit of yield.

With farmland, you are buying a productive underlying asset — unlike a precious metal, which is only worth whatever the next person is willing to pay.

TDU: Can you frame both the bear and bull cases for farmland in the coming years / decades?

CM: Like any other investment, there are macro risks. Climate change is real. That can mean changes in weather patterns and changes in climate overall, depending on where you grow. The risks can be mitigated, but it still must be considered in long-term forecasting. There’s also the micro side — every parcel of land has its own idiosyncrasies, from soil quality to water quality — each of these variables can have a material impact on output.

But ultimately, we view these governing realities as opportunity enhancing. Take almonds for example — something like 80% of the world’s almond supply comes out of California. A lot of those almond orchards are in water threatened areas. But if you go to California to grow almonds, and you are in a geography where you can secure enough water, over the next decade, you could be at a really positive place as other almond orchards are taken out of supply. Supply shrinks, as demand stays steady or increases. That’s a recipe for success.

All Well and Good, But What Does That Mean For Me?

When it comes to farmland, the problem for average investors is there has never been an actionable way to make investments in the sector. Short of having a sibling who marries into Iowa royalty, the attractive financial attributes of farmland have been entirely out of reach.

AcreTrader has entered the market to disrupt how investing in the space works. Importantly, AcreTrader works with farmers who are looking to expand their businesses by, as an example, buying adjacent pieces of land. The farmers remain on as key operating partners, and investors can help drive a massive value unlock.

If you’re interested in learning how Farmland can play a role in your portfolio, check out AcreTrader now.