Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

The venture capitalist-fueled post-modern bank runs in recent weeks have pundits wringing their hands that we’ve learned nothing since the 2008 financial crisis as they call for more and more government oversight. But what if the lessons are for central bankers, not regulators?

The crises at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank were contained wildfires of liquidity losses that somehow shook Americans’ faith in the banking system overnight. But this was no global credit crisis.

The two events do have one major thing in common, however: They both took place immediately after a 20-year era of super-low interest rates that have redefined the notion of risk and refashioned our financial behavior.

The banking sector is indeed much stronger than it was 15 years ago, and regional banks have proven their soundness and worth over and over again. During the pandemic, they handed out billions in PPP loans to clients left unserved by megabanks.

On Thursday, the White House made it clear that it believes the way to restore confidence in small banks and the system overall is to strengthen key elements of post-2008 legislation. But taking that approach alone might be letting our financial PTSD get the better of us. There’s reason to think the true cause of every financial scare we’ve endured since the turn of the millennium has been historically low interest rates and the cheap money addiction they created.

So light the candle in your Jay Powell shrine, clap your hands twice, and let’s get into it.

Assets vs Liquidity

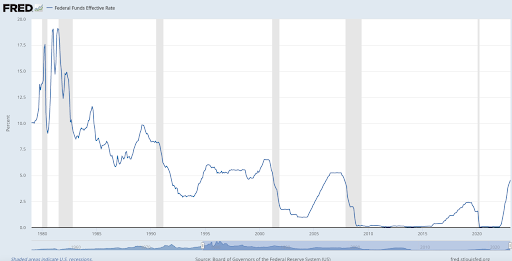

When Lehman Brothers failed in September of 2008, Wall Street was forced to take a hard look in the mirror. Banks of all sizes had become delirious after rate cuts started in 2000; money was cheap and predatory lenders were merry… and busy. Subprime mortgages were all over the loan books of American banks, which simply sold their exposure to large investment banks that saw everything as an asset with rates at 1%.

By 2007, Wall Street’s overall asset quality had crumbled to a tragic level. The Federal funds rate plummeted from over 6.5% to 1% between 2000 and 2004 and then surged back up again to over 5% by the middle of 2006 – that’s the central bank equivalent of pulling back the shades to let the morning light into a dark room teeming with bad decisions.

The legislation that was borne in the aftermath of the crisis — most notably Dodd-Frank – focused on taming banks by instituting new capital requirements and conducting stress tests. But a fully-panicked Federal Reserve had also dropped rates to basically zero by the end of 2008, hoping cheap money flooding the economy would supercharge the recovery.

That new legislation also prompted a wave of bank consolidation:

- In 2007, there were 7,290 banks insured by the FDIC, according to the agency’s own data. By 2012, there were just 6,089.

- Between 2007 and 2012, there were 22 mergers between US lenders.

Smaller banks play a key role in the economy by originating lending and fueling small businesses often outside major metropolitan areas. But by 2021, there were 4,237 banks in the US.

So why didn’t banks grow in the boom?

Blame Interest Rates

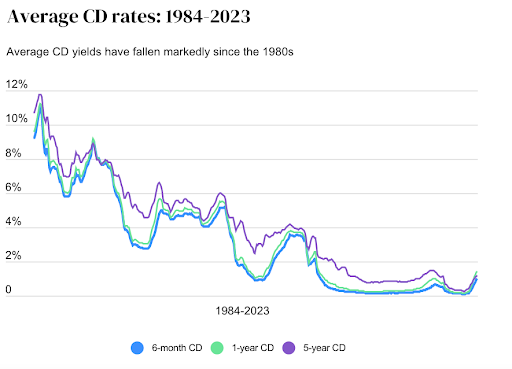

What post-2008 regulation could never really combat was the fact that for the most part, two generations of Americans knew only a world of ultra-low rates. As a corollary, none of them had experienced the pleasant side effect of higher interest rates: that banks will actually pay you to keep money in their coffers.

In 1980, the federal funds rate was over 19%, making it almost a no-brainer for customers to keep their money just sitting in a bank. But that was more than 40 years ago, meaning today’s Millennial and Gen Z depositors ponder staying loyal to a bank forever and think “OK, Boomer.”

For context, a college sophomore in the deepest chaos of the financial crisis is, on average, a 35-year-old today — a legal adult nearly twice over who might have a family, a mortgage, and/or a small business loan. They also have a very historically unique relationship with their savings account, in that it’s never made them money.

Simply put, low rates are not great for banks, but soaring rates are not something bankers like to see either, especially when they didn’t fully plan for Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s aggressive hikes in 2022 and 2023.

“When interest rates go up at the sharpest rate in 40 years, bad decisions are going to be exposed,” said Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate.

But should rates stabilize comfortably above zero, smaller banks have proven they can thrive.

The Secret of NIM

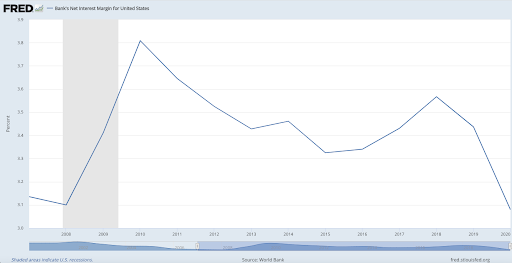

Net interest margin is the key indicator most analysts use to gauge and project the profitability of a bank. NIM compares how much an institution is making on long-term credit products like mortgages or business loans against how much it will pay out in interest on deposit accounts.

The post-2008 consolidation of smaller lenders was a mortgage crisis hangover, forcing small banks with weaker or negative NIM into forced marriages with banks that could absorb their poor credit books. And while the average NIM of US banks dropped with rates close to zero, it glided up in the pre-pandemic rate hike.

All the while, it was regional, well-managed lenders who benefitted the most:

- At the end of 2022, US banks with assets between $50 billion and $99 billion boasted the strongest NIM on average of 3.87%, according to BankRegData.

- In what should have been a signal, both SVB and First Republic had assets of more than $200 billion. Signature was well over $100 billion. While all three had NIMs under 2.9%, SVB’s was 2%.

With rates rising even higher in 2023, the average NIM has taken a hit thanks to an inverted yield curve that counterintuitively incentivizes banks to hold shorter-term debt instead of long-term bonds.

“We’ve got a deeply inverted yield curve that is not helping NIM,” said McBride. “As long as that’s the reality, the deposit move from smaller to larger will only accelerate.”

Another thing that an inverted yield curve stymies is the creation of new banks.

De novo? De nada

As banks reckoned with their near-death experience in the wake of 2008, and cheap money flowed into tech startup “disruptors,” hardly any newcomers entered the business.

So-called de novo banks — adopted directly from the Latin phrase “from the beginning” — are newly-formed lenders that usually crop up in underbanked communities. The growth of de novos had slowed to a historical crawl in the wake of ‘08, consolidating deposits and assets throughout the system, a harbinger of what we saw in the throes of the SVB scare.

De novo growth was something that bank insiders fretted over as the mortgage crisis waned, and for good reason, as nonexistent interest rates made starting a small bank unappealing to investors:

- According to FDIC data, 179 new bank charters were issued in 2016. Between 2012 and 2016, the total was three.

- Many of the 61 de novo charters issued since 2010 were for non-traditional firms looking to create lending businesses.

Consolidation catapulted JPMorgan Chase from number three to number one asset king among US banks. The trend continued even as the Fed began to raise rates in 2015, finally certain that the economy could handle it.

With capital now coming out of the pores of private equity and other investors, those rising rates made de novos a little more appealing. Twenty-five charters were issued between 2017 and 2019. De novos were so popular that trading app Robinhood even applied for one in 2019 before withdrawing the application.

And then came the pandemic. In a cold panic to keep the economy afloat, the Fed pushed rates down even further and literally cut checks to regular people to keep liquidity flowing. In their haste to hand out federal PPP money via banks, the government leaned on large lenders. But it soon found that smaller regional banks were infinitely better-positioned to comply with the “know your client” (KYC) paperwork as they already had more familiar relationships with them.

But while regulators began to once again recognize the critical role of smaller banks, rates had once again dropped to almost zero.

The worsening addiction to cheap money fostered outsized valuations for tech startups like WeWork enjoying a pre-market one of $42 billion. At the same time, near-zero rates created a fervid IPO market, gave new life to SPACs, pumped cryptocurrency, and turned private equity into a capital death star. It also allowed institutions like SVB to indulge a risk appetite that should have been made impossible by the regulatory gastric bypass of Dodd-Frank and other rules.

And it all took place at a time when Americans were being disincentivized to keep their money sitting in a bank account and the creation of new banks was being choked off.

So while we spend the next few weeks and months debating what regulators knew, when they knew it, and what they should know going forward, keep in mind that banks are not as weak as most of us think. But they won’t be as strong as they can be until the Fed can strike that balance of raising rates high enough to choke inflation and letting banks breathe again.