Can Nike Regain its Legendary Standing?

Not only is sportswear and sneaker giant Nike faced with struggling financials, but it is also searching for its soul.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

Plummeting shares? Check. Falling revenues? Check. Billions in cost-cutting, hundreds of layoffs? Check and check. Wall Street analysts calling for new leadership? Check. These are just some of the odds stacked against the world’s most famous checkmark, the Nike swoosh.

Not only is the sportswear and sneaker giant faced with struggling financials, but it is also searching for its soul. Analysts and critics have piled on, questioning a “stale” product line that’s failed to meet fashion trends or a post-pandemic running boom. In January, golf legend Tiger Woods — arguably the most famous and recognizable Nike athlete after Michael Jordan — announced that he had left the brand.

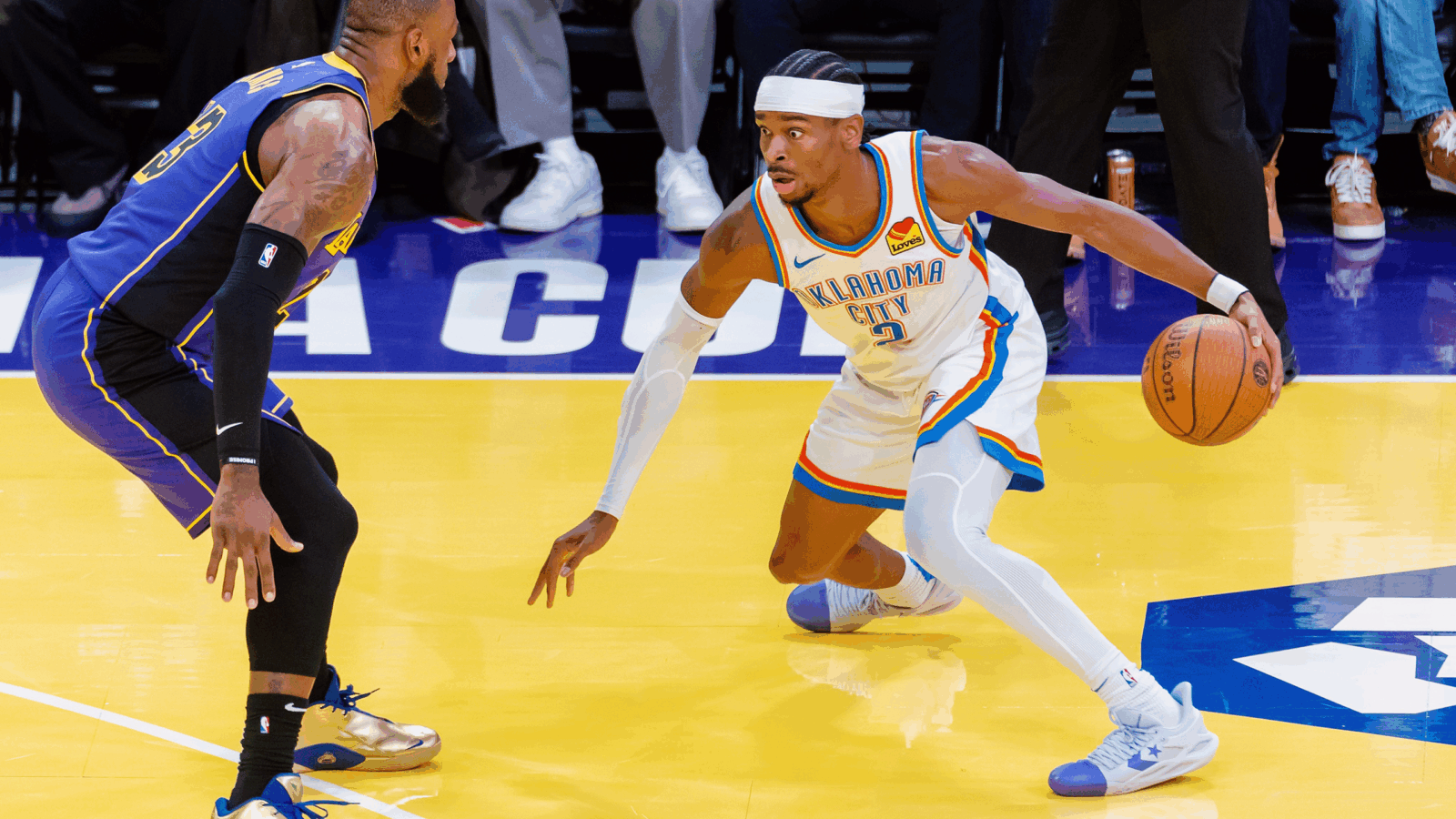

While it may still have endorsements from bullet-fast Vinícius Jr. and Kylian Mbappé, sales are forecasted to dip into 2025, meaning there’s little hope of a recovery that can meet the pace of those top footballers. So how did Nike get here, and where does it run now?

A Lightweight Quarter

On June 28, Nike shares tumbled 20%, marking its worst day on the market since a September 1980 IPO and erasing $28 billion in shareholder value. A day earlier, the company reported a surprise sales drop in the first quarter — revenues fell 2% year-over-year to $12.6 billion. Worse still, the company said revenues will likely decline by “mid-single digits” through Nike’s fiscal 2025 after executives had previously forecast small growth — they also tacked on a warning of a looming 10% drop in the current quarter.

“Our key conclusion is there will be no quick rebound for Nike’s earnings,” UBS analyst Jay Sole said in a research note. “Our base case top-line forecast depends on Nike successfully developing new innovative products, but there is no guarantee this will happen.”

Two weeks later, Nike shares are still hovering at their lowest level since March 2020, when the first wave of pandemic global shutdowns rocked markets, and are down about 30% since the start of the year. They’re also down nearly 60% from their late 2021 high. After the latest financials were released, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan — which understandably saw a potentially undervalued blue chip brand — pulled their buy calls from Nike’s stock.

The June result, rather than an isolated incident, came on the tail of a December announcement in which Nike lowered its 2024 sales forecast and introduced $2 billion in cost-cutting plans over three years: those would include terminating more than 1,500 jobs, or 2% of its workforce. This would be its lowest annual year-over-year growth since 2010, save for 2020’s pandemic slump.

Some Wall Street analysts have even begun to pontificate about changes at Nike’s Oregon HQ. “Management credibility is severely challenged, and potential for C-level regime change adds further uncertainty,” Stifel analyst Jim Duffy wrote in an investor note last month. John Donahoe, who took over as CEO in January 2020, comes from a tech and online payments background, which has led to some rumblings about his suitability to helm the footwear giant.

Blunders and Boredom

One of Nike’s biggest obstacles is one it’s always faced: fashion whims. Many of the brand’s classic shoes, like the Air Force 1s and Air Jordan 1s, aren’t as popular as they once were. The company, for example, said on a March investor call that it was cutting back production on Air Force 1s, with customer sentiment gravitating toward new trends.

But it’s also faced criticism for dipping quality and innovation in its new products. At least one of its signature athletes agreed. When Nike released a limited run of the Book 1, the first signature sneaker of NBA all-star Devin Booker, in December 2023, the shoe was criticized for its uninventive monochrome colorway. Booker himself replied to an Instagram post that asked, “Is Nike fumbling the D Book 1 launch?” with “a lot of people feel the same way,” adding a crying-face emoji.

Just a couple of months later, the company had an even bigger debacle when several Major League Baseball players panned their new Nike-made uniforms. “I think that the performance wear might feel nice,” one player on the Baltimore Orioles told The Baltimore Banner, “but the look of it is like a knockoff jersey from T.J. Maxx.”

Nike acknowledged the MLB issue and pledged to address the design and “flimsy” material; it had previously and more broadly emphasized on investor calls that “newness and innovation” need to drive its overall product lines.

One possible explanation for these particular whiffs — or at least a partial explanation — has been the restructuring under Donahoe’s leadership, which saw Nike reorganized into men’s, women’s, and kids’ divisions rather than divisions focused on individual sports.

Another concerning strategy has to do with direct-to-consumer sales. Donahoe, a former eBay CEO, bet that consumers would switch to online shopping for good after pandemic lockdowns lifted. During the pandemic, Nike expedited a direct-to-consumer strategy started in 2017 and reduced its presence at wholesalers, focusing instead on sales through its website and app.

That backfired, essentially freeing up shelves and floor space at retailers for upstart competitors and established rivals alike. It’s possible that smaller firms, like British sportswear maker Castore, French running-shoe trendsetter Hoka, and Switzerland’s On, may never have had the wherewithal to enter some wholesale spaces without Nike’s withdrawal. Established powers like Adidas and New Balance took advantage, too.

To make matters worse, Nike’s direct-to-consumer strategy hasn’t even worked: Sales at its direct-to-consumer division were down 8% to $5.1 billion in the latest quarter.

Nike warned a few weeks ago that its revenue in the first half of its 2025 financial year would shrink, and said it would cut back on orders of established shoes such as the Air Force 1 as it tries to focus on new, innovative products.

Still No. 1

Nike’s annual revenue — at $51 billion in the year to May 31, 2024 — remains far in excess of Adidas (about $23 billion), Lululemon ($9.6 billion), Puma ($9.3 billion), and New Balance ($6.5 billion). But analysts at HSBC forecast the company’s annual sales growth will lag behind rivals, including Adidas and Lululemon, in 2024, 2025, and 2026.

Hoka’s sales increased 28% to $1.8 billion in its latest fiscal year. On — which won the endorsement of retired tennis star Roger Federer after he ended ties with Nike — expects to increase sales 30% this year to $2.5 billion.

Meanwhile, Adidas, the world’s second-largest sportswear company after Nike, reported an 8% increase in sales to $5.83 billion for the fiscal first quarter of 2024, beating Wall Street expectations. Its shares are up 20% this year.

Comeback Kid? Nike’s plans to cut 1,500 jobs includes more than 700 positions that were recently trimmed at its Beaverton, Oregon headquarters. The Oregonian reported that 40% of those cut in this round were in management, including vice presidents, directors, and senior directors.

While those executives were shown the door, this week Nike brought back a familiar face as part of a seeming admission that its pivot away from wholesalers needs a wholesale rethink.

Tom Peddie, a 30-year Nike veteran, is rejoining the company as vice president of marketplace partners, according to a report by Bloomberg.

Peddie’s job will at least partly involve mending the fences with retailers that the company pulled back from in its direct-to-consumer experiment. Nike had already begun this work in earnest last year, with a return to Macy’s after two years. Another major relationship will be Foot Locker: Despite touting a “renewed” relationship with Nike last year after the shoemaker’s initial wholesale pullback, the retailer plans to reduce its share of Nike products to comprise 55% to 60% of its sales by 2026, down from 70% in 2021. A planned new lineup of footwear priced below $100 — off the back of the $80 Nike Interact Run, released last year — could also be key to stimulating a wholesale revival.

While there’s no timeline for a turnaround, this month’s Paris Olympics will allow Nike to showcase what it does best: go big. Vogue reported last week that the company flew 400 journalists, influencers, and investors to the French capital for a multimillion-dollar, three-day-long promotional festival featuring Serena Williams and other celebrity endorsers. The magazine also noted that Nike intends to spend more on these Olympic Games than in past years.

Nike’s also participating in an Olympic pilot program that allows brands that aren’t official sponsors to be more active during the games, such as promoting wins by their athletes. It will, however, take a lot more than celebratory social media posts to push a Nike turnaround over the goal line.