Finding the Real in Artificial Intelligence

Does the AI hype actually hold any substance? As long as you don’t get distracted by shiny things, these venture capitalists say.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

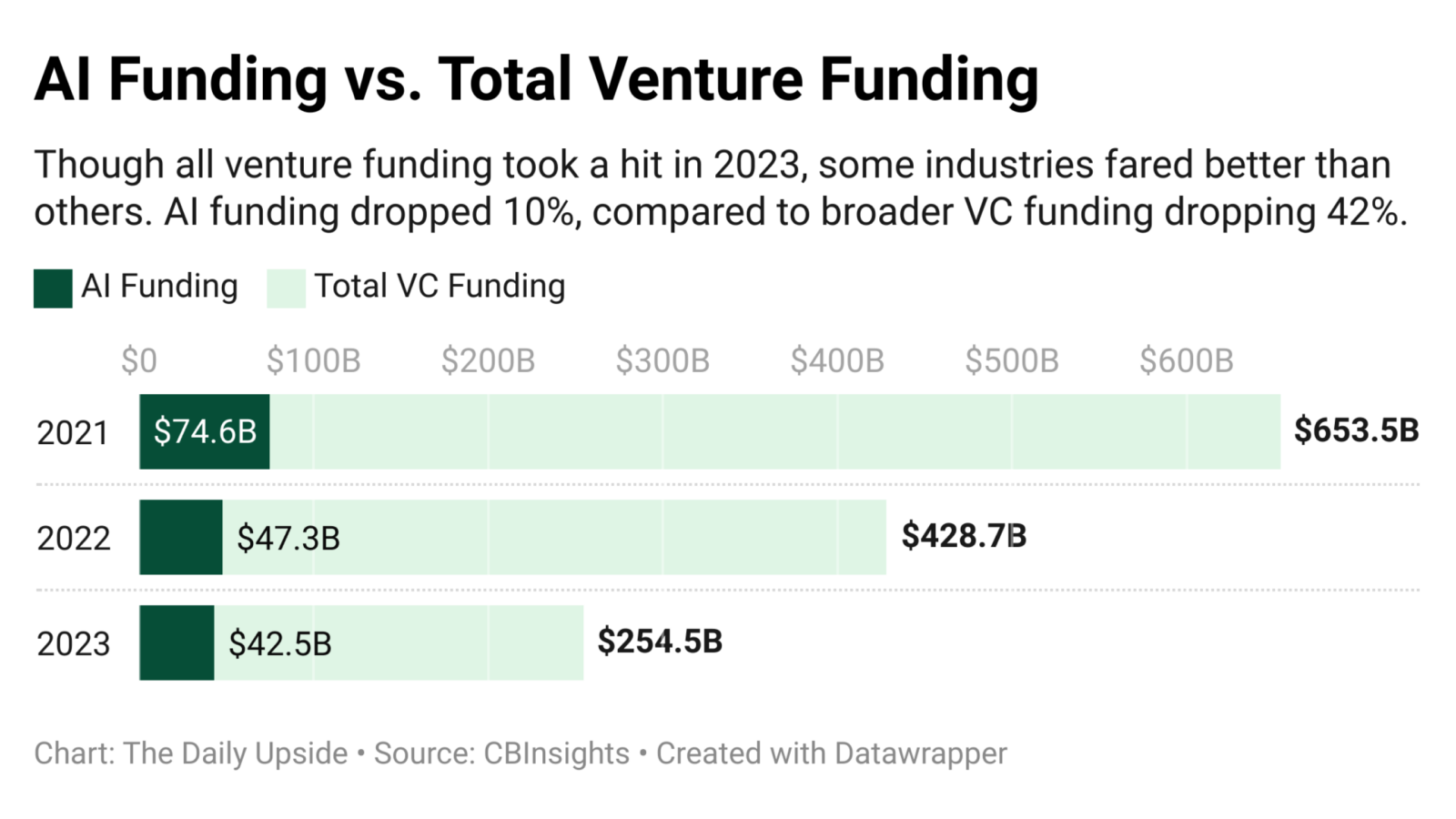

Even as investments in new companies slump, AI startups are still rolling in it. According to CBInsights, AI startups raised $42.5 billion in 2023, with generative AI companies attracting 48% of that pie. Though this is down 10% year-over-year, overall venture funding fell by 42%.

On the surface, the excitement recalls the $3 trillion blockchain boom in late 2021, which led to a crypto crash just months later that wiped out $2 trillion in value. Venture capital investors told The Daily Upside that the AI hype may hold more substance — as long as you don’t get distracted by shiny things.

Panning for Gold

But in a crowd of AI startups vying for attention and cash, distinguishing between the good and the bad, especially in a fast-moving market where investors and customers alike fear being left behind, isn’t easy. Here’s what the pros say they are looking for in an AI startup.

Instead of hopping on the bandwagon, Los Angeles-based Fika Ventures has taken a more conservative approach, general partner Eva Ho told The Daily Upside.

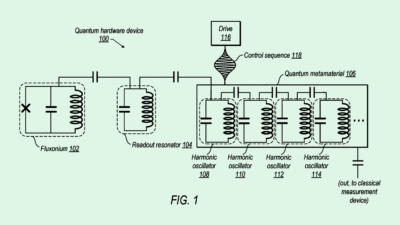

In previous startup booms, the capabilities of the software itself were hardly ever the risk when investing, said Ho. But with AI constantly morphing, “the technology risk is much higher to assess.” Generally, the more an AI model promises, the more things can go wrong, she noted. “You’re always balancing between creativity and power of a model and ability to constrain it.”

- The main question that Ho and her firm ask themselves when assessing an AI startup is: Can it scale? No matter how tantalizing the vision is, Ho said, it’s vital to look beyond just what a prototype can do to determine if a model can effectively work for a growing customer base.

- “You can build a pretty sexy, constrained demo by refining a model … and because you’re seeing it in these demos it seems pretty interesting. The hard part is, how does it actually happen?”

The next step is figuring out who a new AI technology is trying to help. One good indicator is the AI founder trying to make the world “fundamentally better,” said Ho. “When I hear a pitch, I try to think about, if this were to exist, how would life be different? How will a student’s life be different, or how will the nurse’s life be different? I want to see some step change in the quality of their work or their play or their day-to-day life.”

David Waxman, partner at Santa Monica-based TenOneTen Ventures, takes a similar approach. For him, a sign that a company is using AI correctly is “when a problem that used to be intractable is suddenly solvable.” That’s especially true if the praise comes directly from the customer:

- This is why TenOneTen looks at less-sexy use cases for AI, like industrials, logistics, and healthcare. Sectors where AI can support dwindling human workforces also catch his firm’s attention, Waxman noted. “We’re having a skilled person shortage in many, many industries.”

- For example, Regard, an AI-based note-taking and diagnostic platform in TenOneTen’s portfolio, stands to take busy work off of physicians’ plates. The tech could provide much-needed support amid the looming shortage of healthcare workers in the US. The company recently expanded its partnership with health system Banner Health, bringing the tech to 33 hospitals in six states. “They’ve skated to where the puck is going,” Waxman said.

And if a company has built its own AI models, data is as good as gold. Because it’s so hard to compete with big companies like OpenAI, Google, or Microsoft, “If you can bring your own proprietary and customer data that no one else has, then you’re doing things that no one else can catch up to,” Waxman said.

All Sizzle, No Steak

With the expanding promise of AI comes the mounting pressure to do something with it – even when it’s not entirely necessary. Many startups see no choice but to put their technology out there, often driven by customer demand or the pace of innovation by competitors.

That sets up many startups for failure, Ho said. Companies that didn’t have a solid customer base or a strong product fit think AI is “going to be (their) white knight,” she said. When in reality, Ho added, “There are a lot of things in the world that still don’t need AI, to be honest.” Those cases signal to Ho that a founder may be “easily distracted,” joining a trend without understanding the consequences.

Besides the major ethical and privacy issues with jumping into AI carelessly, startups also risk destroying their original mission.

Waxman has identified two camps of startups that have flocked to AI’s promise. One type comprises companies trying to remake themselves into AI firms by shoving the technology “where it’s either inapplicable or peripheral” to score funding and premium valuations by “riding the wave”:

- Finding AI “substance” isn’t always about the technology itself, said Waxman. The most important factor is the problem founders are trying to solve — and whether there’s money to be made in trying to solve it. “If the founders seem more informed about the tool than they do about the industry, that’s a red flag,” said Waxman.

- Not having a clear picture of the market signals that the startup may not actually understand the industry’s needs, Waxman said. It’s like trying to sell a pair of hiking shoes when you’ve never walked more than a mile.

The second type are companies that aren’t traditionally AI firms but are finding ways to use AI tools to make their products better. Such startups tend to have more substance than the former. But with so many companies that are “all sizzle and no steak,” Waxman said, customers and investors can get inundated and eventually burned out, unable to tell the difference. “That’s detrimental to the ones that are actually, really doing something interesting,” Waxman said.

Vexed VCs

Founders aren’t the only ones getting distracted. Investors can be just as distractible, said Ho. “The game has changed, none of us truly know how to play, and everyone is trying to learn the rules.” And because AI is so front-of-mind, the wins and losses are amplified.

While fear of being left in the dust has certainly inflated deal prices and valuations, the billion-dollar question is whether betting on a wild card is better than not betting at all, Ho said. “Would you rather just stay on the sidelines and do nothing?”

The winners and losers of the AI boom probably aren’t going to be decided by a monumental crash, said Ho. Rather, it’s more likely to shake out like a “gradient,” with one end being the impractically confident and less-stable bets and the other being the technology that made a real difference. That will show itself as the technology develops, she noted, but for now, there are no guarantees.

“I think there will be an economic collapse of people who may have made overly optimistic investments,” said Ho. “I don’t think there’s gonna be innovation collapse.”

The best thing an investor can do is try to understand the technology as much as they can. Knowing the model and its intentions is a big part of choosing between the gold and the glitter.

“It’s important that you understand what the technology can and cannot do,” Waxman said. And to put it simply, “some investors are better than others.”