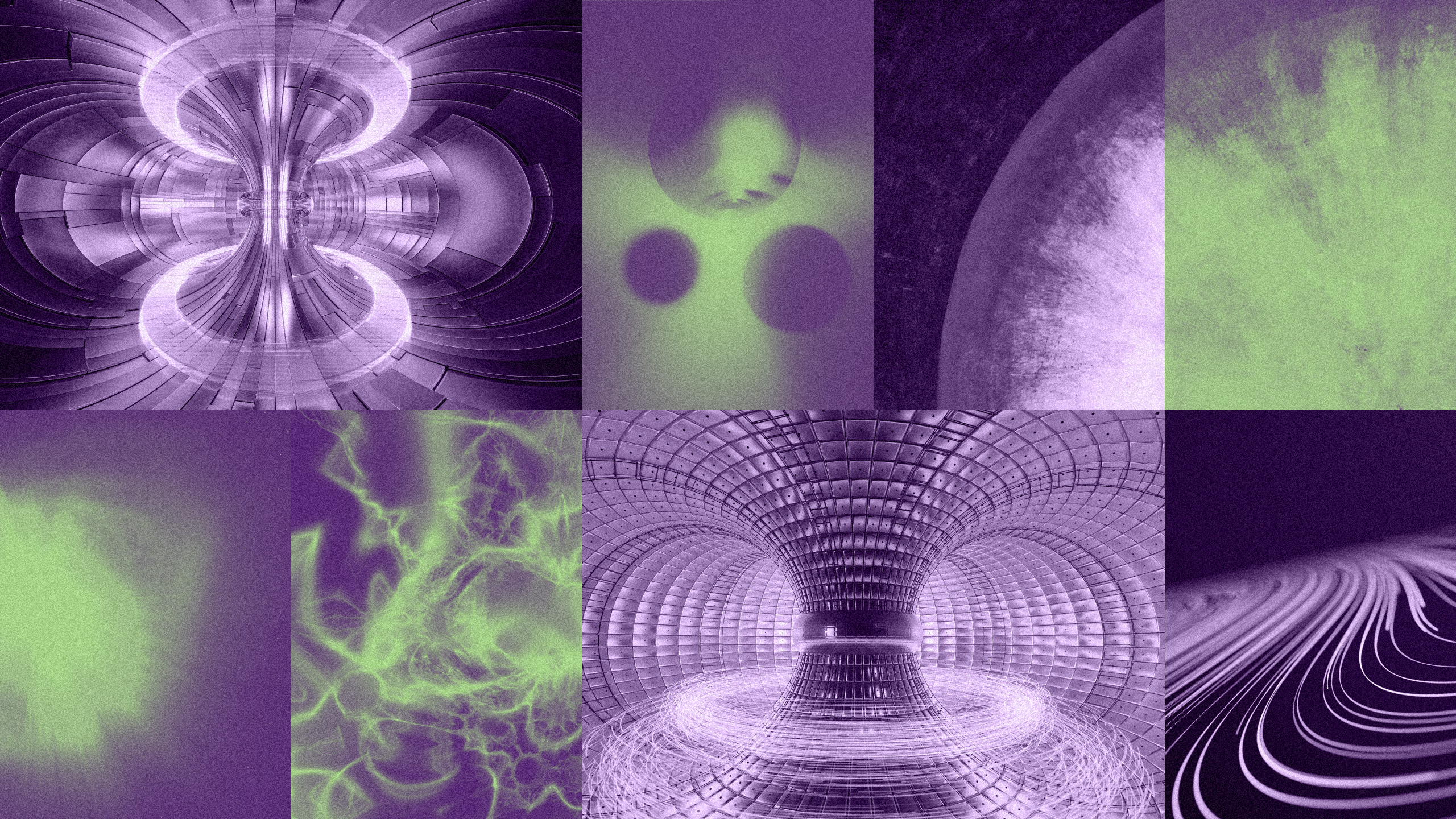

Will Power-Hungry AI Be the Catalyst for a Nuclear Fusion Breakthrough?

Has the dawn of the nuclear fusion age arrived? One developer of the powerful energy-generating tech says it will be available in 10 years.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

Living in the age of artificial intelligence sometimes feels like stepping into science fiction, but it masks a harsh reality: AI, above all else, is power hungry, sucking the world’s energy grid dry even in its infancy and driving electricity bills sky-high.

The sci-fi problem may require a sci-fi solution, and some scientists and tech hyperscalers are pinning their hopes on an energy source long relegated to the world of theoretical physics: nuclear fusion.

Under development since about the time humans first went to the moon, the technology is advancing more rapidly now. In 2022, the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory achieved a breakthrough: producing 3.15 megajoules of energy from 2.05 megajoules of input energy, the first successful net-gain fusion reaction in history. It’s a feat that has since been achieved multiple times, turning the theoretical into the real.

Perhaps more importantly, billions in funding have since poured into a burgeoning nuclear fusion industry, moving the science from its longtime home in universities and public labs into private enterprise, with the ultimate goal of commercialization.

But is the dawn of the nuclear fusion age actually here, at long last?

“[We will have] fusion on the grid, delivering electrons reliably to end customers within a decade,” Brian Berzin, co-founder and CEO of Thea Energy, told The Daily Upside.

While it’s a bold prediction, experts say it’s grounded in reality.

The Holy Grail

Let’s pause for a minute, because we know what you’re thinking: Isn’t nuclear power already widely deployed?

Yes, it is. But that’s nuclear fission; this is nuclear fusion. Consider it a football-futbol type of difference. Sure, both sports involve teams of 11 players trying to move a ball down a similarly sized field to score, but the similarities stop there.

Fission is the type of nuclear power that’s been around for decades. Homer Simpson works at a fission power plant; Chernobyl, Fukushima Daiichi and Three Mile Island were all fission plants.

Fission captures energy from splitting a heavy uranium atom; fusion captures energy from smashing two light hydrogen atoms together so fast that they fuse into a new, heavier atom.

A naturally occurring phenomenon inside the sun and every star, fusion could produce several times more energy than fission and exponentially more than gas or coal. Even better, a major fusion power plant will theoretically produce about as many radioactive isotopes (nuclear waste) as the average medical imaging device. In other words, a negligible amount compared with fission. And, crucially, it is theoretically immune to the type of chain reaction meltdown that has turned fission into a public policy boogeyman.

Low-waste, low-risk, extremely powerful.

“In some sense, we like to think about fusion as the Holy Grail of energy sources,” Troy Carter, Director of the Fusion Energy Division at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, told The Daily Upside.

But, as with every Holy Grail quest, the search for fusion has proven extraordinarily difficult, if not outright impossible.

One Step at a Time

For decades, operating a particle accelerator to smash atoms together required more energy than it created. Post-NIF successes are still barely above the break-even energy point. And the entire process requires equipment that can withstand temperatures of at least 100 million Kelvin (about 179 million degrees Fahrenheit; remember, this is the process that occurs inside the sun).

In simpler terms, the commercialization of fusion energy requires cracking a theoretical physics problem, engineering brand new technologies to capture energy, designing a power plant that can actually house the sophisticated operations and securing a highly specific supply chain to source all the required materials.

Then there’s the matter of commercialization: “You have to compete for cost with other generation sources, because at the end of the day, you will not sell a single electron if the market will not pay for it,” Yasir Arafat, chief technology officer at fission startup Aalo Atomics, told The Daily Upside. “If you’re going to be 10 times more expensive, it does not matter how clean you are, how awesome you are, right?”

‘Soup to Nuts’

Painfully aware of that, the industry is nonetheless pressing ahead.

Thea Energy, which has achieved break-even energy generation, last month became the first of eight fusion-focused startups in the US Department of Energy Milestone-Based Fusion Development Program to receive initial design approval of its fusion power plant.

“[The DOE brings] in experts from science and fusion physics, and they bring in experts from engineering, and they bring in experts from commercial power, and then to kick the tires, soup to nuts,” Berzin said. “We’re thrilled to be the first company to get through that.”

Thea is one of a handful of companies benefiting from a surge in venture capital investments over the past few years, alongside Commonwealth Fusion and TAE Technologies. Last year, private funding for fusion technology reached $3.8 billion globally, a 476% year-over-year increase, according to the market intelligence platform Sightline Climate. Virtually all the top startups were spun out of existing university or national laboratories. Thea, for instance, traces its origins to the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, where researchers spent decades perfecting the “Stellarator,” a high-powered fusion power device now at the center of Thea’s business.

‘Credible But Challenging’

“For the Stellarator to get the proof points that we needed to now commercialize, to take the final step, it took 70 years,” Berzin said. “And a lot of breakthroughs that happened over the past five years now enable us at Thea to commercialize it … There’s no more wild discoveries, no moonshots or miracles that we need to commercialize.”

Those 70 years featured a roller coaster of public investment and interest. According to research from the Institute for Progress, a non-partisan innovation think tank, annual US fusion funding grew from about $24 million in 1967 to a peak of $468.5 million in 1984, fueled by the 1970s energy crisis. Public funding tapered off for years afterward.

Berzin says the company will break ground on its first power plant by the end of the decade and plans to put fusion energy on the grid by 2033 or 2034.

“They’re definitely ambitious,” Carter said of the private sector’s roughly 10-year delivery timetable. “I’m optimistic … Electricity produced from fusion in the 2030s, I think there is a credible but challenging pathway to that.”

Carter also noted that most researchers believe that a purely public-sector-driven mission could have delivered fusion energy to the grid by the 2040s. “The private sector is able to move much quicker and take on more risk. I mean, the public sector is notorious for taking forever to build facilities, just because it has to be very conservative, and it’s got to work, right?”

Sliding Down the Cost Curve

According to Berzin, the energy from the first Thea power plant will probably cost about $150 per megawatt-hour. That places it in the highest end of wholesale electricity prices; while charges vary by region and season, US Energy Information Administration data shows that monthly prices from current mass-scale energy sources floated around the $50 per megawatt-hour mark last year.

Berzin says prices will decrease with scale: “You can’t make your Nth power plant, your 10th, your 100th, at $100 per megawatt-hour. At that point in time, you better go down the cost curve to $50 to $60 per megawatt-hour.”

It’s another crucial point, and why fusion remains an anomaly in energy. In traditional baseload energy generation using natural gas or coal, for example, the fuel is the driver of incremental cost increases per megawatt-hour. Electricity prices rise because of a change in natural gas prices, for example, not because of the cost of turning natural gas into electricity.

“Fusion turns that on its head, because the fuel is hydrogen. [It requires just] liters of hydrogen to power Manhattan,” Berzin said. “The tough part, though, is the machine. So the economic driver of that now becomes the machine to make the fusion happen, not the cost of fuel.”

And if developers manage to pull off the moonshot of fusion energy generation and deliver it at competitive prices, what comes next? All the industry has to do is maintain highly technical, first-of-their-kind fusion power plants for decades to come.

“Fission, fusion, combined cycle, natural gas power plants, jet engines, aircrafts, these are very complicated pieces of machinery,” Berzin said. “There’s a lot of precision, there’s a lot of complexity. We spent a lot of time thinking about how this gets manufactured, how that gets clearly put together with nuts and bolts and welds in construction crews, and then how that gets operated for 40 years.”