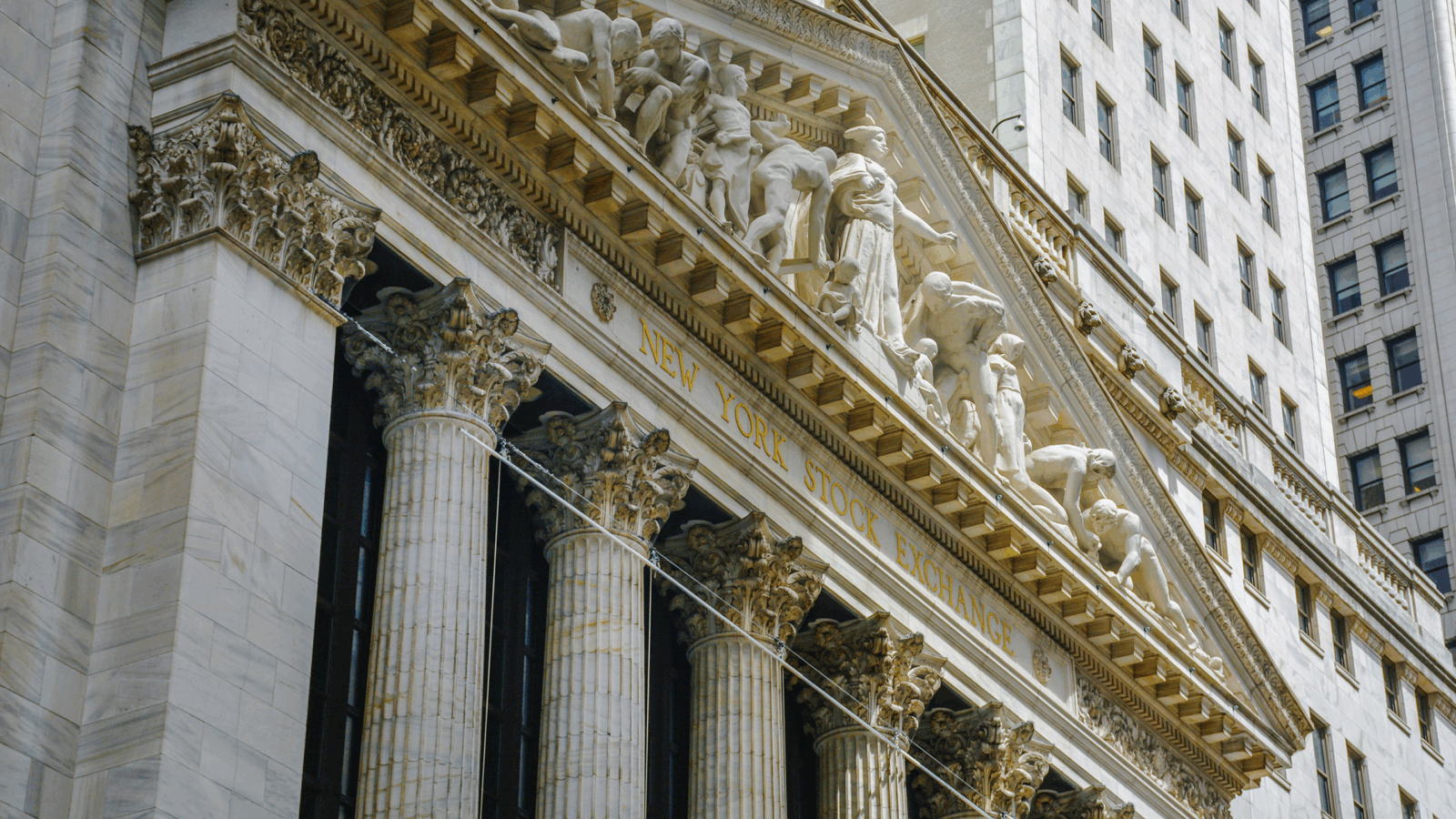

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

Don’t call it a comeback. Call it a greenback.

Russia’s expanding quagmire of a war in Ukraine and the imposition of sanctions on Russia have led global skeptics of the American dollar to call for an end to its status as the world’s reserve currency of choice. The greenback responded by hitting a two-year peak this week.

Green Still In on Blue Planet

For years, Chinese authorities have been pushing the narrative of the need to end the dollar’s reign as the world’s reserve currency — a fact of global economic life since the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement. To some, the massive scale of the penalties doled out to Russia over its invasion of Ukraine seemed like an opportune moment to resume talk of toppling the king of the hill.

As much of the Western world imposed sanctions against Russia, several major economies — China, India, Brazil, and Mexico — chose to remain neutral, requiring alternative currency arrangements when trading with the aggressor nation. Arrangements like these, the IMF warned last month, could create small currency blocs that dent the dollar’s position as a global reserve currency. “We are already seeing that, with some countries renegotiating the currency in which they get paid for trade,” IMF managing director Gita Gopinath told the Financial Times. Still, the dollar’s appeal to investors is holding fast:

- The dollar rose to 101.86 against a basket of rivals this week, a level not seen since March 2020. The Federal Reserve’s recent rate hikes have been followed by higher US debt yields, suggesting markets are confident the Fed can tame inflation, and bringing foreign investors to US Treasuries.

- Unlike the Fed, the European Central Bank has been unwinding prior pandemic-era stimulus measures at tortoise speed. The ECB must weigh fears that rate hikes would lead to a selloff of debt from Spain, Italy, and Greece by pushing yields on more desirable German debt above those for the Mediterranean countries’ bonds. That scenario would spell trouble for the euro.

“The dollar typically performs in two extremes: in a scenario of risk aversion, or in a scenario where the US is a clear outperformer,” Kristen Macleod, co-head of global foreign exchange sales at Barclays, told The Wall Street Journal. “What we have seen over the past couple of months—since the Russia-Ukraine conflict kicked off—is the dollar is benefiting from a bit of both.”

Not So Fast: The dollar makes up 59% of central bank holdings, already the lowest level in a quarter-century. Earlier this year, Blackrock CEO Larry Fink warned the global economy is about to fragment even more: “The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put an end to the globalization we have experienced over the last three decades.”