In High-Distribution ETFs, Not All That Glitters Is Gold

Too often, investors waste a significant portion of their income by failing to pay attention to the tax implications of the ETFs they hold.

Sign up for market insights, wealth management practice essentials and industry updates.

Clients have sacrificed and saved after-tax income for retirement. The IRS and most states want to thank them for all the taxes they’ve paid. Now they’re ready for retirement, a time when their money needs to work for them, and you should make the tax code work for them as well. Too often, we see investors waste a significant portion of their income by failing to pay attention to the tax implications of the ETFs they hold.

ETFs with high distributions, or dividends, may appear like bright, shiny objects, but not all that glitters is gold. From a tax standpoint, many high-distribution ETFs provide only fool’s gold. There is an old saying that neither death nor taxes can be avoided. If you are prudent, however, the latter can be minimized. Not all ETF distributions are taxed the same way. In a taxable account, look for ETFs that optimize after-tax income by having a significant portion of their distributions treated as a tax-free return of basis, also referred to as a return of capital. Allow us to explain.

Point of No Returns

For simplicity, and since the tax implications are the same, we use “ETFs” here to refer to exchange-traded funds (ETFs) held in a taxable, non-retirement account.

For clarity, all distributions taken from a retirement account that was funded with pre-tax contributions (e.g., traditional, non-Roth IRAs) are taxed as ordinary income, regardless of whether they were generated from dividends, interest or even your original capital. In retirement accounts, assets that produce the best risk-adjusted returns are optimal since neither distributions nor taxes are relevant.

However, imagine you saved additional money in a taxable brokerage account. In that case, the nature of the ETF’s distributions can make a huge difference in how much of those distributions you get to keep after tax. Remember, it’s only what you get to keep after tax that matters.

Most investors get a consolidated 1099 income statement from their brokers. Many investors just hand the 1099 to their accountant and pay what their accountant tells them to pay. However, ETF distributions are not generally taxed only as dividends. In fact, given the tremendous growth in derivative-based strategies, particularly those designed to provide high levels of current income, it is increasingly important to understand the composition of those distributions from a tax standpoint. Failure to do so can result in losing up to half of the pre-tax distributions to taxes that could either have been delayed or even avoided entirely.

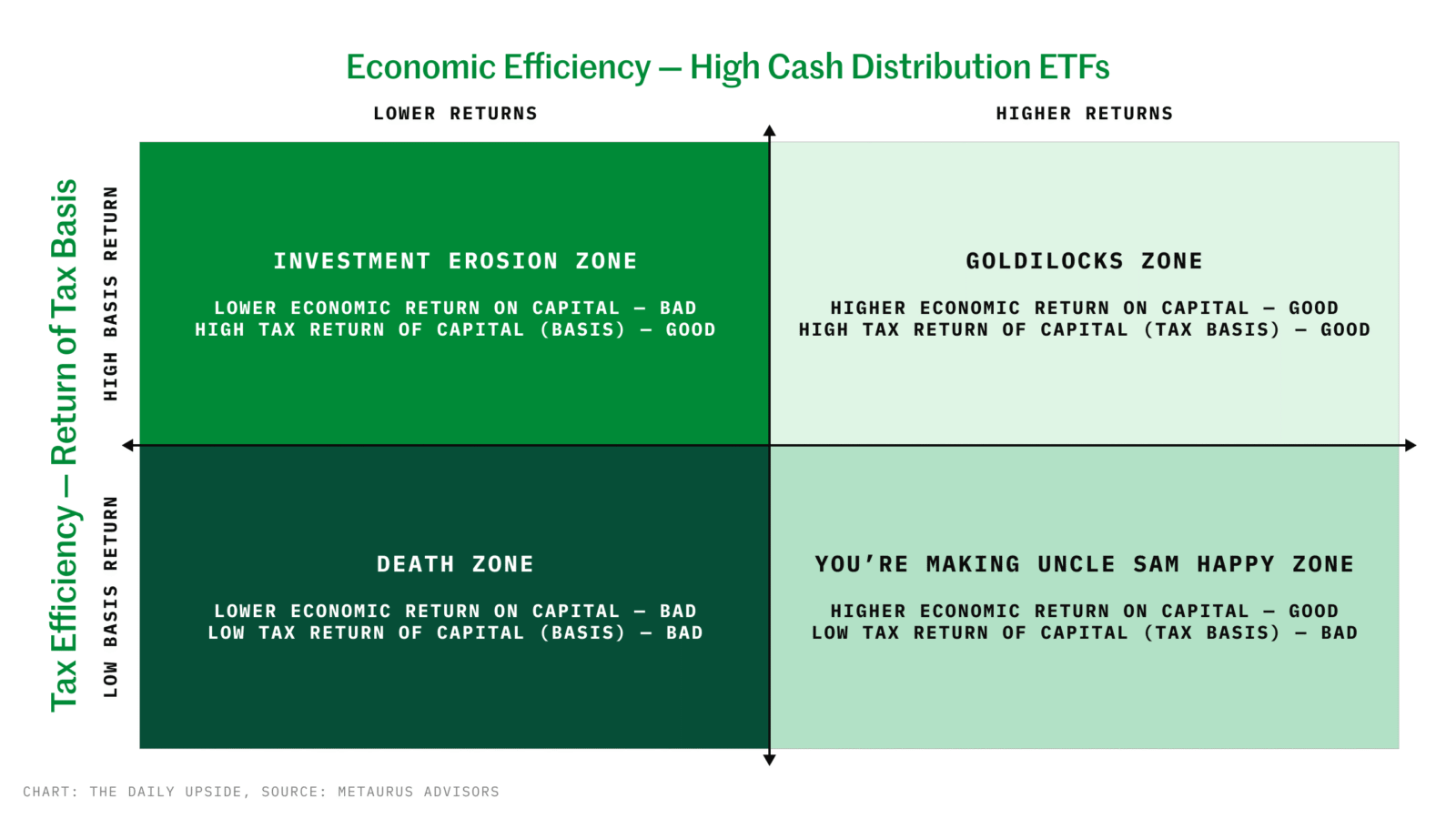

It is important to differentiate an economic return of capital from a tax return of capital. Many investors use these terms interchangeably, which often leads to confusion. From an economic standpoint, return of capital simply pays investors back their own money, thereby reducing the capital on which future returns can be earned. This is analogous to a farmer eating his seed corn, the seeds that would otherwise be used to grow next year’s crop. However, from a tax standpoint, when an ETF can classify a portion of its distribution as a return of capital, it is more accurate to think of this portion as a tax-free return of the investor’s tax basis. Just because a portion of an ETF’s distributions is classified as “return of capital” from a tax standpoint doesn’t necessarily mean your principal is being eroded. It simply means you’re paying less in taxes.

Paying More Than You Need To

As previously stated, when most ETFs pay a distribution, it doesn’t mean that distribution is simply taxed as a dividend. In fact, each ETF must identify the source of its distributions including a) interest income, b) dividends, c) realized capital gains or losses, or d) return of capital (i.e., return of tax basis). While traditional fixed-income ETFs predominantly source their distributions from interest income and traditional equity ETFs source their distributions from dividends, a new wave of derivatives-based ETFs may achieve their distribution objectives from some or all of these sources. The tax impact to investors depends on the type of derivative instruments used. While most funds have a mix of sources, from a tax standpoint, only d) above, return of capital, is tax-free.

Since return of capital for tax purposes represents a tax-free return of tax basis, selection of the wrong ETF can result in wasting your tax basis and paying significantly more taxes than you need to pay. ETFs with the highest proportion of their distributions classified for tax purposes as return of capital (i.e., a tax-free return of basis) are the most tax efficient. Most investors are used to this concept in stock investing (investors recover their tax basis before determining any amount of capital gain or loss).

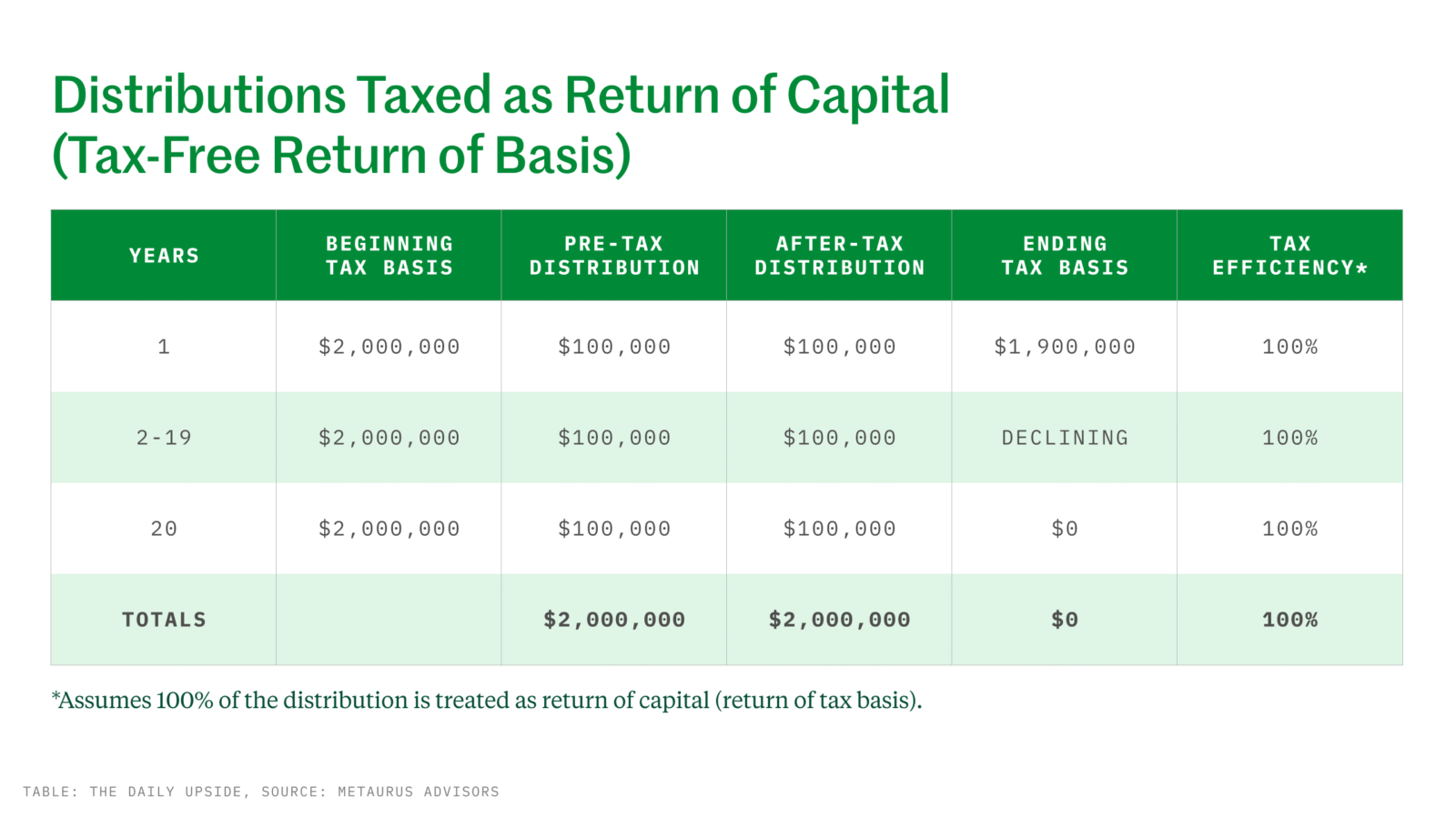

The best possible scenario is an ETF where your capital is increasing, but your tax basis is decreasing due to a portion of the distribution being classified as a tax return of capital (basis). In short, the portion of the distribution that is classified for tax purposes as a return of capital can make an enormous impact on what you get to keep after taxes. And while the numbers may vary by individual, the lesson holds for all individuals with assets beyond those in their IRAs. Let’s consider a few examples.

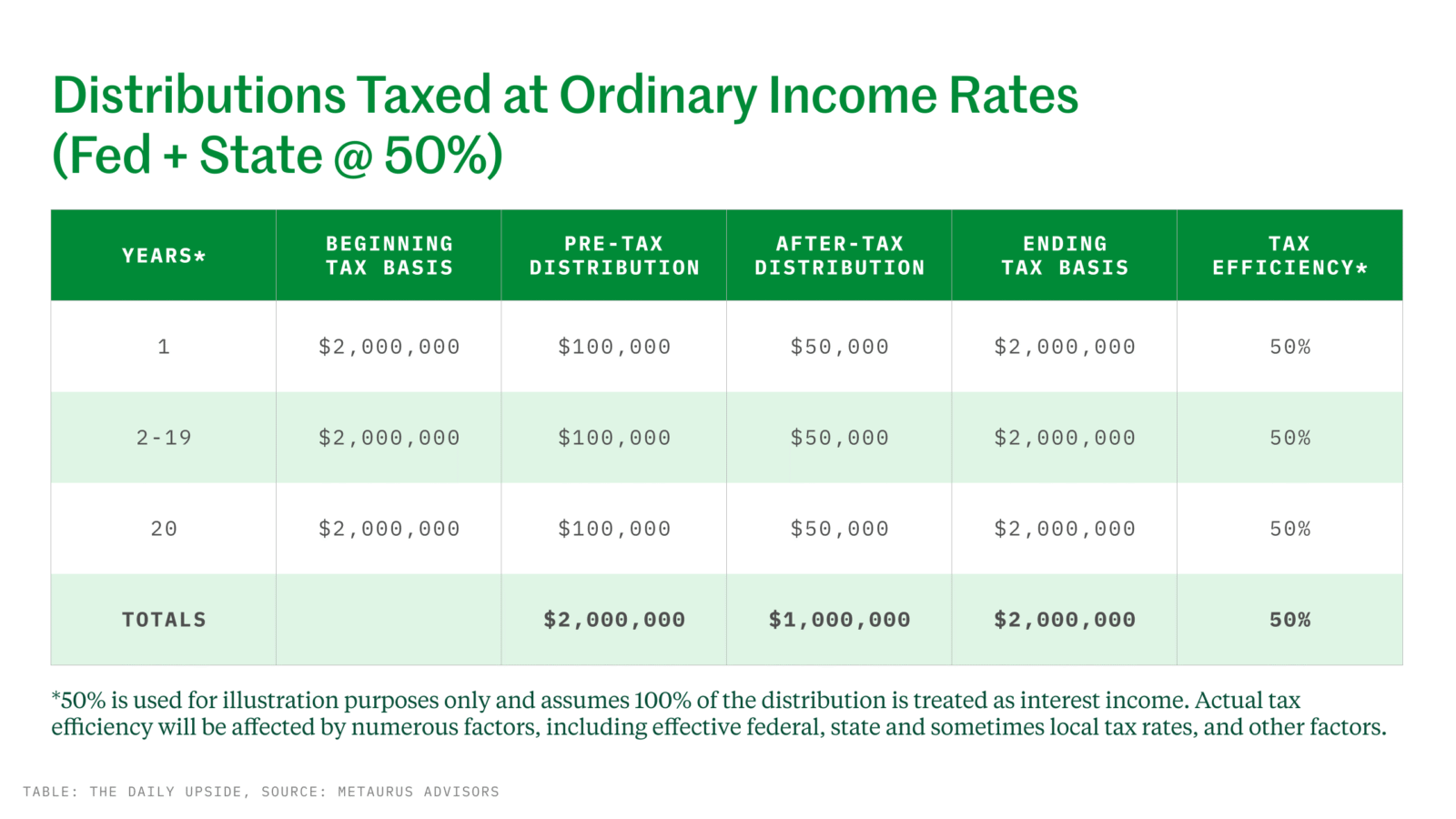

Assume you are 65 and have saved and invested $2 million after-tax, in addition to your taxable IRA. For simplicity, assume your tax basis in these investments is also $2 million. From an actuarial standpoint, you might expect to live another 20 years. Seeking more income from your assets, you elect to invest in a diversified ETF that produces higher annual cash flow that is generated by high dividend stocks, corporate bonds or even option premium. You want to produce a pre-tax distribution from your ETF of around 5% per annum. This would mean $100,000/year, or $8,333/month, in pre-tax distributions. However, it is important to understand how each strategy’s distribution is treated to determine how much of it can be kept after tax. Whether it’s interest income, dividend income, capital gain, and/or return of capital (tax basis), the tax composition of the distribution will result in different tax liability.

Case A: Interest Income

If ETF distributions are classified as interest income, they would be taxed at ordinary income rates. If you are lucky (or unlucky) enough to be in the highest federal marginal tax bracket and live in a state with state income tax, you might keep only about half of the pre-tax distribution after tax. Therefore, your tax “efficiency” is about 50% (“efficiency” defined as after-tax divided by pre-tax).

This applies to all taxable fixed-income ETFs. Some specialty funds reclassify all K-1 tax form components as interest income, while many derivative-based, high-distribution ETFs that receive cash predominantly from structured notes generally need to classify this portion of the distributions as interest income. ETFs that generate most of their distributions from interest income are the least efficient. To take our original example, over 20 years, this investor might pay over $1,000,000 in taxes, with the investor’s tax basis being unchanged.

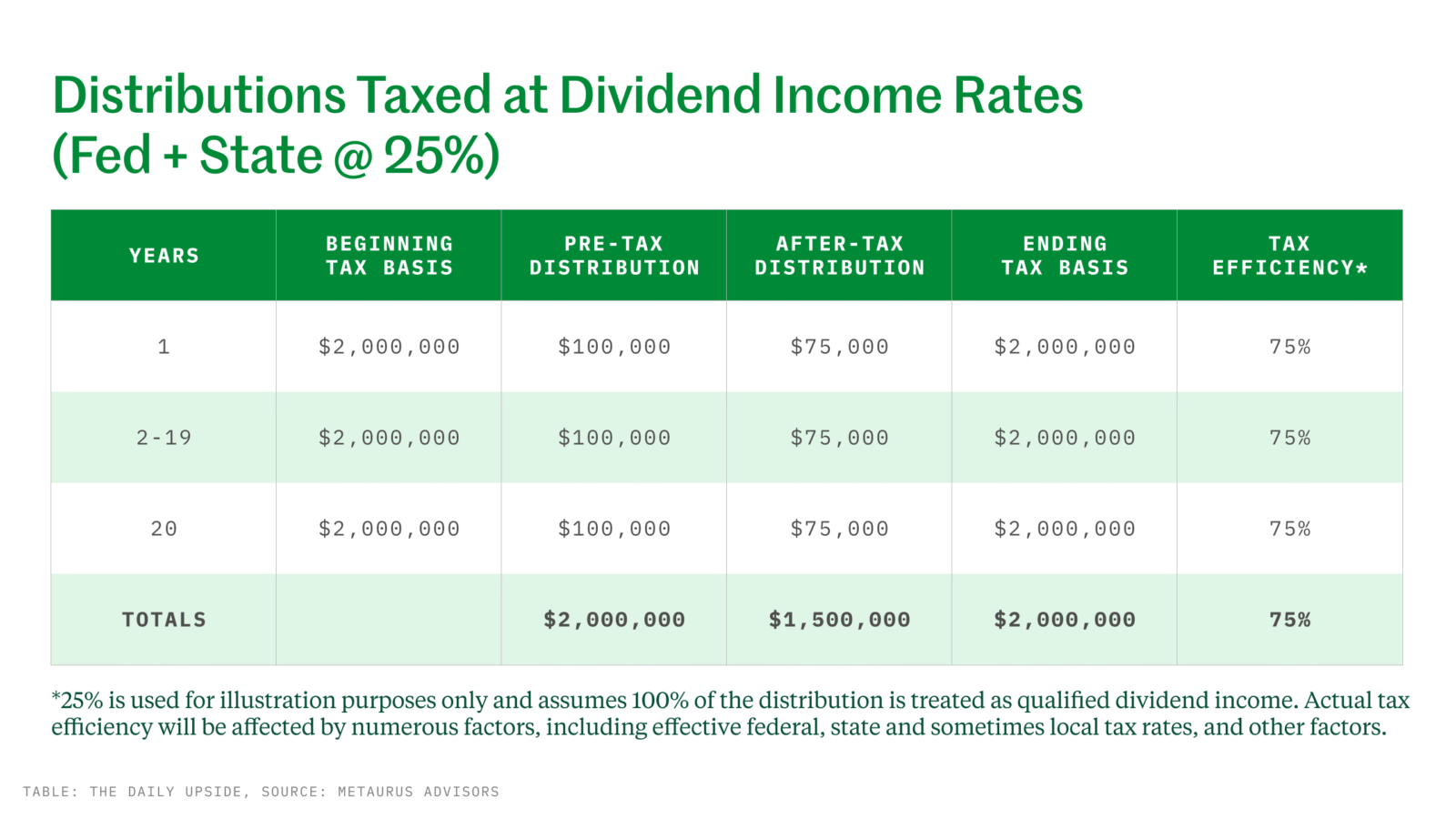

Case B: Qualified Dividends

If an ETF has predominantly qualified dividend income, the tax rate is roughly half that of ordinary income. If all the ETF’s distributions are taxed as qualified dividends, over the same 20 years, this investor still might pay over $500,000 in taxes. However, unlike capital gains, there is no possibility to offset dividend income. Finally, there would likely be little to no reduction in tax basis.

Case C: Capital Gain / Loss

All ETFs are required to distribute 90% of their net investment income, including net realized capital gains. ETFs that trade their assets more frequently (higher turnover) or ETFs that utilize derivative contracts to derive cash distributions will often have some capital gain to distribute. ETFs that employ exchange-traded index derivatives have a blended capital gain/loss of 60% long-term and 40% short-term. Fortunately, savvy ETF managers can often employ various means to offset some portfolio gains within the ETF. In addition, individual investors might be able to use available capital losses to offset some capital gains. The tax efficiency would be better than in Case A, but there are too many ETF-specific and individual factors to determine a uniform tax efficiency. Still, there would likely be little to no change in tax basis. So here an investor could lose a quarter or more of these distributions to taxes. Investors in ETFs that make distributions sourced primarily from capital gains, over the 20 years, might pay over $500,000 in taxes, again with no reduction in tax basis.

Case D: Return of Capital (i.e., Non-Taxable Return of Tax Basis)

Any portion of an ETF’s distributions that is treated as return of capital for tax purposes is not taxed at all. So, if a significant portion (or all) of the ETF’s distributions are taxed as return of capital, over the same 20 years, this investor might pay substantially less, or nothing at all, in taxes. Like before, there may be no erosion of capital from an economic standpoint. If the cost basis has been exhausted down to zero, any future capital distributions would be taxed as capital gains. Nevertheless, the investor has delayed paying these taxes well into the future. Ultimately, these taxes may never be paid at all, as we illustrate below.

Here is the final yet critical point. When an investor dies, for estate tax purposes, their tax basis is irrelevant, and any remaining tax basis is essentially forfeited. After estate taxes (if any), the new owner assumes the value of the asset(s) as of the date of death, and this value becomes their new tax basis. So, investors who fail to exhaust their tax basis in their lifetime end up paying taxes that may have been avoided entirely.

So where should investors go for tax-efficient income today?ETFs with good economic returns and the highest portion of their pre-tax distribution classified as return of capital for tax purposes (a.k.a. tax-free return of basis) are much closer to pure gold as investors keep far more of their distributions after tax (i.e., they are the most tax efficient). In the end, investors who choose ETFs with good economic returns while also returning their tax basis may avoid a substantial portion, if not all, of the taxes altogether.

Richard Sandulli is Co-CEO of Metaurus Advisors LLC

Nicholas R. Brown is a Senior Tax Partner at Sidley Austin LLP