What’s Going on With Muni Bonds?

Investors appear to be punishing the muni market, which comprises about 9% of the $47 trillion US bond industry.

Sign up for market insights, wealth management practice essentials and industry updates.

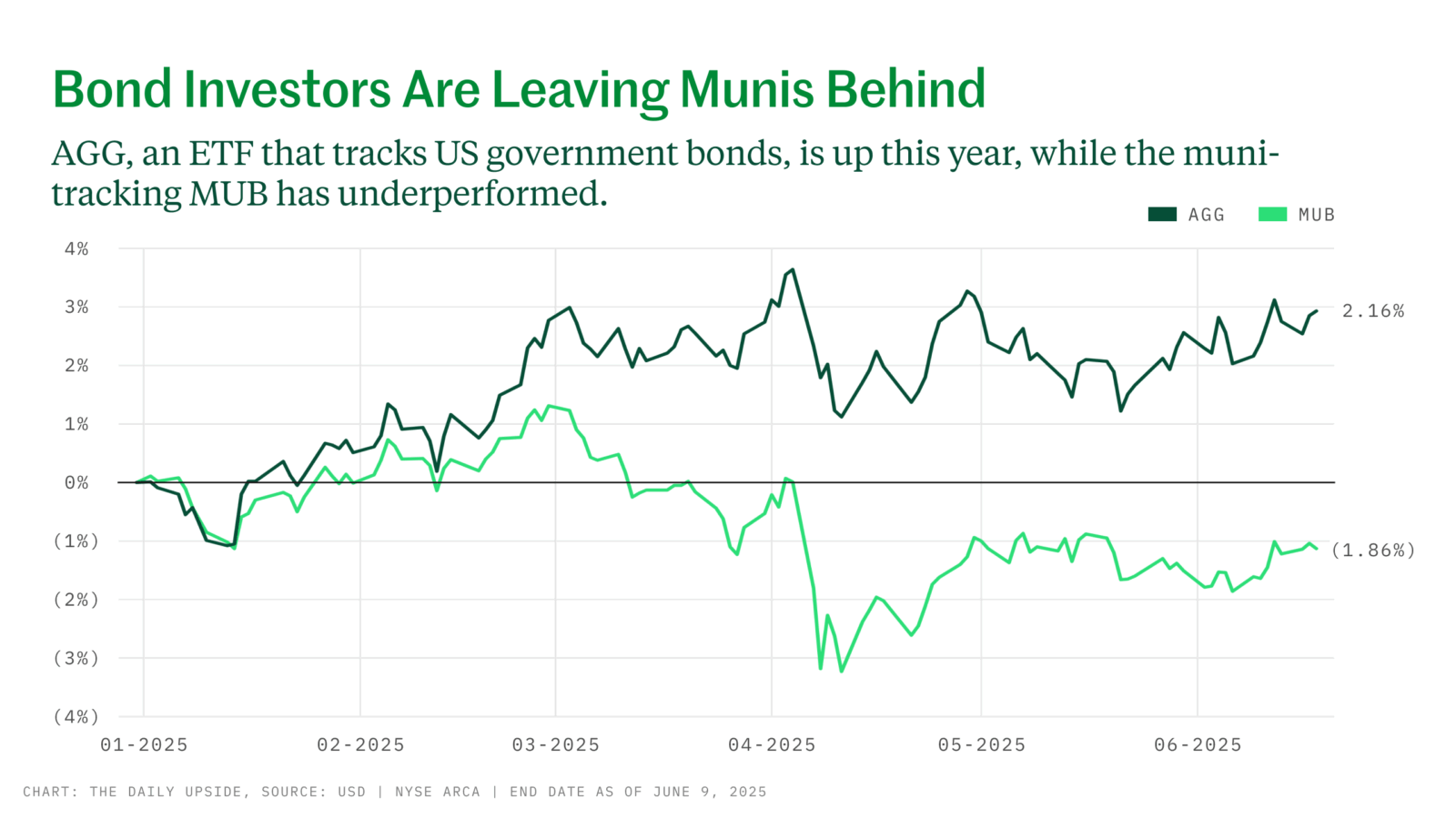

Nearing the mid-point of the year, it’s been a relatively good period for most investment grade bonds. Not so much for municipal bonds.

The iShares Core US Aggregate Bond ETF (AGG) gained 2.85% while the iShares National Muni Bond ETF (MUB) lost 1.29% through June 17. That’s a differential of 4.14 percentage points. Both numbers include dividends paid. But the biggest difference between the two funds is that the municipal bond fund is federally tax-exempt as the bonds are issued by states and municipalities, while the US Core Aggregate bond fund is taxable (though part is state tax-exempt for most states). Yet they are quite similar in other ways. Both are high quality, moderate duration, and low-cost bond funds with Morningstar showing the following as of June 11, 2025:

- AGG has an average credit rating of AA-, while MUB is rated at AA.

- AGG’s effective duration is 5.81, while MUB’s is 6.76.

- AGG’s annual expense ratio is 0.03%, while MUB’s is 0.05%.

Though AGG has a slightly lower credit rating, investors often run to US government bonds in uncertain times, and the majority of AGG are US government or government agency bonds. If that’s the differentiator, one would have also expected corporate investment grade bonds to have done poorly. But the iShares Broad USD Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (USIG) actually gained 2.95%. Even junk (below BBB) has done well. So it would appear the market is punishing only the muni market, which comprises about 9% of the $47 trillion dollar US bond market, according to the SIFMA. So, what’s going on?

Why Munis are Lagging

First, let’s check in on liquidity. The self-regulatory body Municipal Securities Rule Making Board (MSRB) reports that “purchasers of municipal securities tend to be ‘buy-and-hold’ investors and the vast majority of fixed-rate municipal bonds and notes are not traded on a regular basis after the trading that occurs when they are new issues.” Thus, unlike with Treasurys and investment grade corporate, bid-ask spreads for munis tend to be large. They can easily be more than 100 basis points and, in an extreme example many years ago, one client paid a 10.25% spread (or 1,025 basis points).

Year to date, MUB has seen a net outflow of $1.22 billion or a bit over 3% of its assets. Whenever funds have to sell the underlying bonds to meet redemptions, bid-ask spreads are being paid. Sales in a relatively illiquid market cause prices to decline.

Oh, Those Tax Laws? Going into the year, there was more uncertainty as to whether the TCJA tax cuts of 2017 would be made permanent. Higher tax rates would have made munis more valuable. Markets are now probably pricing in the high likelihood of these tax-cuts at least being extended. But perhaps markets are also pricing in the rising federal budget deficit and mushrooming US debt. Eventually, it is likely to catch up to us, and one way of addressing it could be to eliminate the tax-exempt status of municipal bond interest.

Lastly, there may be upcoming reductions in federal funding. The federal government funds a substantial portion of state and local governments. According to the Tax Policy Center, 27% of state and local revenue in 2021 came directly from the federal government. There is a possibility the current administration will cut this funding, and the ever-increasing US debt may eventually make cutting mandatory. Thus, state and local governments could be stressed, spurring an increase in muni defaults.

A Portfolio of Munis

Many clients who come to me don’t need munis. They may be in a very high tax bracket but often have stocks in their tax-deferred accounts and munis in their taxable accounts. The simple solution is to sell the munis in the taxable account to buy stock index funds and then sell the stock funds in the tax-deferred accounts to buy higher-yielding, high credit quality, taxable bonds in the tax-deferred accounts. That increases returns while decreasing risk.

For clients who do need munis, I limit them to 20% of their total fixed income. That’s roughly twice the overall US market percentage of munis to investment-grade fixed income. Munis are riskier than Treasuries. Even with some very aggressive assumptions and some pretty spectacular stock gains over the last decade, states and municipalities have an estimated $1.37 trillion of unfunded pension and healthcare liabilities. If stocks falter for long periods of time, the pension assets will fall and this shortfall between assets and liabilities could surge as baby boomers retire and pension payments continue.

Finally, on average, 89% of muni bonds issued are callable. That means, if interest rates rise, the bonds are unlikely to be called and the duration of the bond earning a below-market interest rate will increase dramatically.

Optical Illusion. I typically recommend against owning the bonds themselves because of lack of liquidity (expensive to sell) and because it’s hard to get enough diversification. Also, nearly every client coming to me owning individual municipal bonds has been a victim of what I call “the muni bond illusion.” Munis are typically issued at a premium and mature, or are called at par. The MSRB allows that return of principal to be called “income.” The SEC yield isn’t perfect, but doesn’t use this illusion.

While owning a bond fund doesn’t eliminate the big bid-ask spreads, typically the spreads are smaller with large amounts than selling, say, $10,000 of an individual bond. Finally, buying a bond and holding to maturity in no way eliminates interest rate risk.

What Now? Munis have had a pretty bad start to the year relative to most investment grade bonds. This means yields are now higher. Those in higher tax brackets with no additional room in tax-deferred accounts for more bonds should consider investing in a high-quality, low-cost muni bond fund. But limit the amount to no more than 20% of your total fixed income. They are not risk-free.