Battlefield AI Grapples With Risk-Tolerance Minefield

Future battlefields will be shaped by AI weapons that defense firms and Big Tech are vying to build for the military. Guardrails are lagging.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

What does the battlefield of the future look like?

The answer, influenced throughout history by advances in weapons technology from iron swords and gunpowder to fighter jets, is increasingly dependent on artificial intelligence tools that traditional defense contractors and Big Tech firms alike are vying to develop for the military. Though these firms stand to make billions of dollars, how best to regulate the known and unknown risks of AI in battlefield situations that threaten the lives of soldiers and civilians alike remains undetermined.

“There can be real benefits if we do this right,” said Betsy Cooper, founding executive director of the Aspen Policy Academy. “We can make a lot of progress in shoring up our defenses and in understanding what our adversaries are doing. It just means we need to walk before we run.”

“Big Five” Versus Big Tech

Defense technology has long been dominated by a powerful group of legacy vendors – the likes of Lockheed Martin, RTX, Northop Grumman, General Dynamics and Boeing. Their AI and machine-learning initiatives include RTX’s AI-powered Radar Warning Receiver for aircraft, Lockheed Martin’s deployment of generative AI tools, and Northup Grumman’s wielding of AI to counter drone swarms.

The “big five” contractors, however, often “don’t represent fast, iterative hardware development and defense tech development,” said Ryan Gury, CEO and co-founder of drone technology firm PDW.

Big Tech can move a little faster, he added:

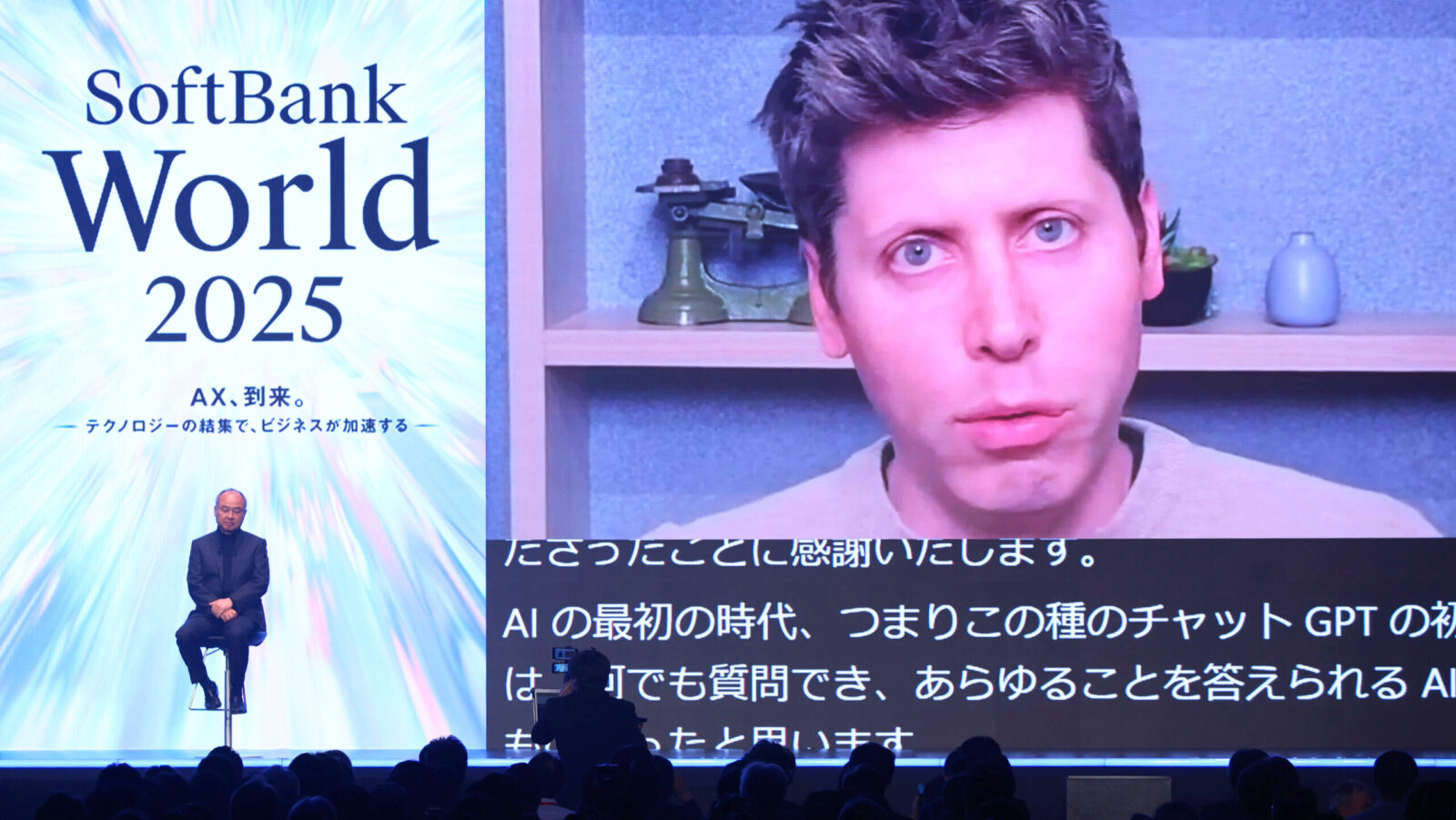

- In December, OpenAI announced a partnership with defense firm Anduril to develop and deploy AI systems focused on countering potentially lethal attacks from unmanned aircraft for national security. The partnership will focus on “counter-unmanned aircraft systems” to “detect, assess and respond to potentially lethal aerial threats in real-time.”

- Google ended its self-imposed ban on using AI in weapons in February. The ban started in 2018 when the company did not renew its contract with the Air Force working on Project Maven, the Pentagon’s flagship AI project using computer vision to automatically detect and track potential targets. Palantir, meanwhile, has inked deal after deal for its contribution to Maven, the most recent agreement being with NATO, struck in late April.

- Microsoft has long worked in government and defense contracting, with recent moves including its own partnership with Anduril and supplying AI-powered Azure offerings for all defense operations.

“There’s a big shakeup right now, because both startups as well as large tech companies … have been able to move very rapidly in developing the leading edge solutions,” said Christian Lau, co-founder of Dynamo.ai. “Those folks who are deep within that underlying technology can deliver much more robust solutions and can operate fast.”

It makes sense that tech firms are turning to defense as they seek to generate revenue from their AI capabilities, said Tim Cooley, president and founder at DynamX Consulting. To put it simply, they’re following the money. Congress agreed on $883.7 billion in defense spending in 2024, with large amounts earmarked for “disruptive technologies,” including AI.

“Everybody wants a little piece,” Cooley said, noting that when military procurement officers review proposals, they’ll be aware of the buzz surrounding AI. “If I don’t have AI in my proposal, I’m competing with people that are going to have it,” he added. “It’s almost a necessity these days in certain areas.”

Humans at the Helm

AI’s ability to quickly absorb and synthesize data gives it a wealth of use cases in the military. Behind the scenes, the tech has transformative potential in supply chain management, security and logistics, said Karl Holmqvist, founder and CEO at Lastwall. “There’s a lot of different initiatives that are going on to enhance organizational efficiency,” Holmqvist said.

On the front lines, AI can be used for real-time threat detection, accurate targeting and surveillance, Cooley said. Autonomous machines, such as drones, also tend to rely on AI for their underlying technology.

“The battlefield of the future is going to look much different than it does today,” Cooley said. “With less humans in the loop, humans are going to be more battlefield managers and less, in some ways, actual combatants.”

Still, the military has struggled with tech going haywire in the past. At the height of the Cold War, for example, erroneous computer warnings that Soviet missiles were heading to the US prompted the military to prepare for imminent nuclear confrontation. While AI is more advanced than late 1970s technology, it isn’t immune to glitches. The tech still struggles with hallucination, bias and data-security issues that can be amplified if not caught. “The really important thing that people need to remember is that this technology is changing faster than humans,” said Holmqvist.

For example, Cooper said, if a model used in surveillance or threat detection experiences a hallucination, it could lead to misleading intelligence that has domino effects for operations. Or, if a user within the defense department trusts a generative model with sensitive and critical data, Lau said, they run the risk of that data being extracted via cyber attacks.

“There’s lots of risk incorporating technology that isn’t fully tested and still has some of these issues into such sensitive work,” Cooper said. “I think we haven’t fully captured the guardrails that we would want to have in place to make sure some of these challenges don’t occur.”

Another challenge is that AI is only as good as the data it’s built on, said Cooley. If that data is corrupted, or even incomplete, it could produce an AI system that falls prey to false positives and false negatives. For instance, if an AI-powered sensor is trained to detect certain kinds of enemy planes, but was trained with a limited data set, it’s “going to pick up something and say it’s a threat, when it might be an ally,” said Cooley.

“Deploying AI can empower the warfighter,” said Lau. “It could empower these agencies to be much more efficient and productive, but also can expose them to new risks from adversaries, particularly foreign adversaries.”

Risk and Responsibility. Despite AI’s pitfalls, there may be more risk involved in not pursuing the tech, said Holmqvist. Similar to the battle to claim AI supremacy in the private sector, the concern that foreign adversaries are adopting this tech as fast – if not faster – than the US has created “a fear factor that’s driving adoption,” Holmqvist said. “If we don’t adopt the technology, there’s a problem — and if we do adopt the technology, there’s a problem.”

“Our enemies are currently using it on the front lines,” said Gury. “So it’s a balancing act. How long do we want to wait?”

That balancing act comes with major ethical considerations, especially with AI implementations on the battlefield. While background deployments of the technology are unlikely to cause ethical qualms, said Lau, more human oversight will be needed as the risks — and the potential consequences — grow larger.

That means keeping a human in the loop any time AI is involved in making choices that can potentially harm people – and knowing whom to point to when it makes mistakes, said Holmqvist. “There needs to be an understanding that we always need to be able to draw lines of responsibility back to who made a decision.”

The above article was updated on May 5, 2025, to correct the name and title of the Lastwall executive.