How AI Helps Doctors Fill Patient Care Gaps

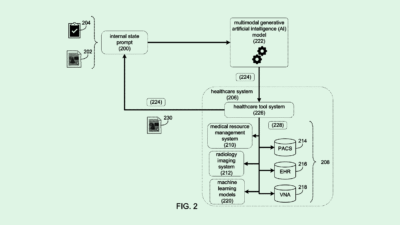

Pangaea Data’s new platform aims to improve medical treatments by informing doctors of patients’ health histories and potential diagnoses.

Sign up to get cutting-edge insights and deep dives into innovation and technology trends impacting CIOs and IT leaders.

Doctors only get so much time with their patients, and sometimes that means things get missed.

That’s an experience Vibhor Gupta, the founder of Pangaea Data, is familiar with. He has seen family members suffer from a late diagnosis or suboptimal treatment even when their medical information was available. Getting the right treatment can feel like an odyssey-level journey, to the detriment of the patient’s health.

“In those moments, you feel practically helpless,” Gupta said. “You’re always thinking to yourself, ‘Well, what good is all the education and everything else that you’ve gone through if you can’t really help the people who are close to you?’”

That’s what led him to form Pangaea Data, an AI health tech startup whose new platform helps clinicians identify diagnoses and cut treatment costs.

“There’s a lot of promise that [AI] holds at a conceptual level,” Gupta said. “For us, it was about carving a niche for ourselves and then being part of that value chain in complement with all of these solutions upstream and downstream from us, so we could do our part and plug that gap.”

Bolstered by all of a patient’s medical records, AI can play a role in early detection, determining a course of treatment or even identifying an applicable clinical trial.

“If technology could help you get to those answers easier at the point of care, you can imagine immediately that benefits pharmaceutical companies as well, because the pharma companies also are motivated to do what’s best for the patients,” Gupta said.

However, he warned against relying on tech as the end-all, be-all. He framed it as a means to an end.

‘Not Like Self-Driving’

“You let the clinicians — who are the ones who are interacting, as humans, with the patients who are also humans — [make] the final call and then take into context whatever information they’re getting from the technology,” Gupta said. “It’s not like a self-driving thing … You still need to be looking at the road, and you still need to keep your hands on the steering.”

AI, just like clinicians moving from medical school into their practice, is constantly learning, developing and evolving, and needs to be granted room for error and evolution.

“Going forward, my hunch is that [AI will] change the way we practice health care, much like some of these self-driving vehicles are changing the way we travel,” Gupta said. “We are seeing a different model of health-care delivery, and I think this will be particularly important for rural health care, where we might not have as many doctors and facilities as would be ideal, but at least we can deliver the same quality and standard of care.”

AI isn’t a cure-all, Gupta said, but an aid that can help patients, especially in rural areas, obtain quality care despite their doctors’ education, patient load or even local infrastructure.