Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

There have been plenty of drivers of economic volatility this year, but an elite military unit led by a former French Legionnaire is definitely a new one.

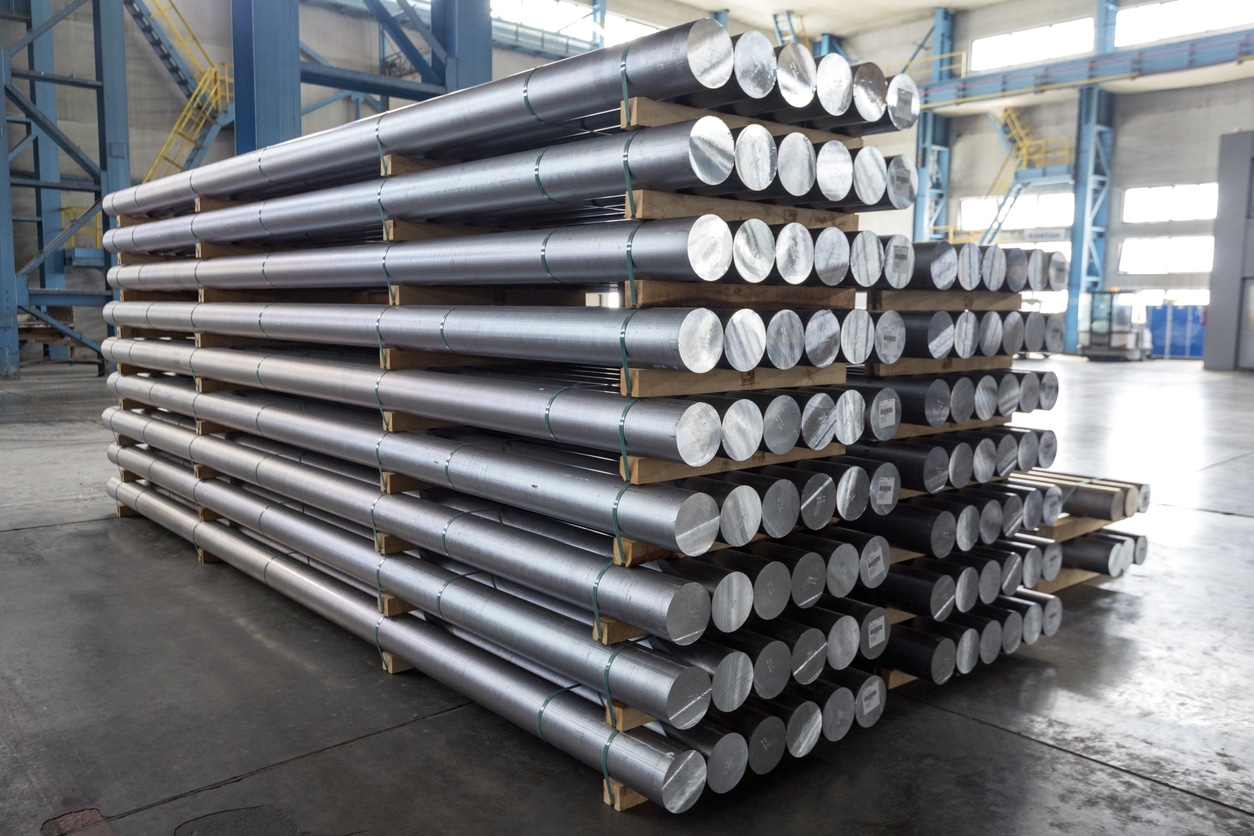

Aluminum markets were rattled Monday, with prices for the metal reaching a 10-year high in London, one day after a coup d’état occurred in the West African nation of Guinea, a key mineral market.

Metals 101

If a quarter of the world’s bauxite supply were suddenly in jeopardy, your first question would likely be, “What’s bauxite?” Well, it’s a raw material that’s refined into alumina, which can be smelted into aluminum, the versatile metal in everything from beer cans to airplanes.

As the world’s second-largest bauxite producer, Guinea exported 82 million tons in 2020, more than any other country. In other words, instability in Guinea is bad news for the aluminum supply chain. So the market reaction was hardly surprising after the events of Sunday, when an elite military unit seized power, arrested the country’s president, and suspended its constitution:

- Aluminum prices on the London Metal Exchange rose 2% to $2,775 a ton, the highest since 2011, and futures in China jumped 3.4% to their highest level since 2006.

- Aluminum has already climbed 40% this year on the back of a stimulus-sparked demand surge, leaving the metal’s biggest producer, China, struggling to keep up.

Upside Pressure: Guinea supplied 55% of China’s bauxite in the first seven months of the year, which has analysts fearing further price hikes ahead. “The increased uncertainty around the new political regime may disrupt global commodity export flows and also raises the likelihood of export contracts renegotiation, which may put upside pressure on alumina and aluminum prices,” said JPMorgan analysts in an investment note.

G’Day For Some: Australia, the world’s largest producer of bauxite, saw shares in its commodity sector rise Monday. Aptly named Aussie miner Alumina Limited, for example, was up 3%. On the other side of the coin, electric vehicle makers, already beset by chip shortages, are now looking at even higher production costs.