The Rise of India’s Reckless Retail Investors

Regulators worry that undisciplined and inexperienced investors are taking on way too much risk in the country’s overheated stock markets.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

You know the story. It was the pandemic. Everyone was locked down and it got boring. In search of something to do, a lot of restless young people — restless young guys, especially — stumbled into freewheeling, exciting investing communities that told them they could become millionaires overnight by playing the stock market.

Maybe a friend clued them in; maybe the Reddit or YouTube algorithm guided them to a “finfluencer” or two.

But this is not a story about meme stocks and the swashbuckling retail traders who drove up the share prices of companies like GameStop, AMC, and Bed Bath & Beyond, squeezing hedge fund Melvin Capital out of existence in the process.

It’s the story of their brethren in India, where a mirror frenzy of retail traders has exploded in recent years and where, in just the past few months, regulators have signaled concerns that too many undisciplined and unwise young investors are taking on way too much risk at the same time that analysts fret the country’s stock index — still buoyed by other strong economic indicators — is in line for a correction.

Under the Finfluence

In July, Mumbai-headquartered Axis Mutual Fund told the Financial Times that it found the number of active traders in India increased more than eight times — from under half a million to 4 million — between pre-pandemic days and last year.

“There’s no other form of legalized gambling,” Ashish Gupta, the chief investment officer at the mutual fund for Axis Bank, told the FT.

Indeed, many retail investors were driven to the exciting, if risky, prospect of betting on markets by some of the same factors that led to betting’s rise in America: Namely, the proliferation of cheap apps that made trading easier and more accessible and a rise in online investment influencers and communities.

“If there are three or four people giving us very objective, good advice, there are seven others out of 10 who are probably driven by some other considerations,” Nirmala Sitharaman, India’s finance minister, said last year about the rise of finfluencers. The FT, in its July report, noted that the organizer of one summit for finfluencers — many of whom have charged fees for courses and advice — acknowledged only 1% of the people there would likely make any money.

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has taken increasingly steep measures to address concerns, forcing regulated entities to cut ties with finfluencers (some had partnered with brokers and mutual funds), ordering takedowns of over 15,000 websites by unregulated finfluencers, and requiring those who wish to provide advisory services like daily stock investment and trading call advice to register with regulators.

Last May, SEBI went so far as to ban YouTube sensation P.R. Sundar, a top finfluencer with more than a million followers on the platform, from the securities market for one year for allegedly providing advisory services without obtaining the proper registration (he admitted no wrongdoing as part of the settlement).

Good Reasons to Invest

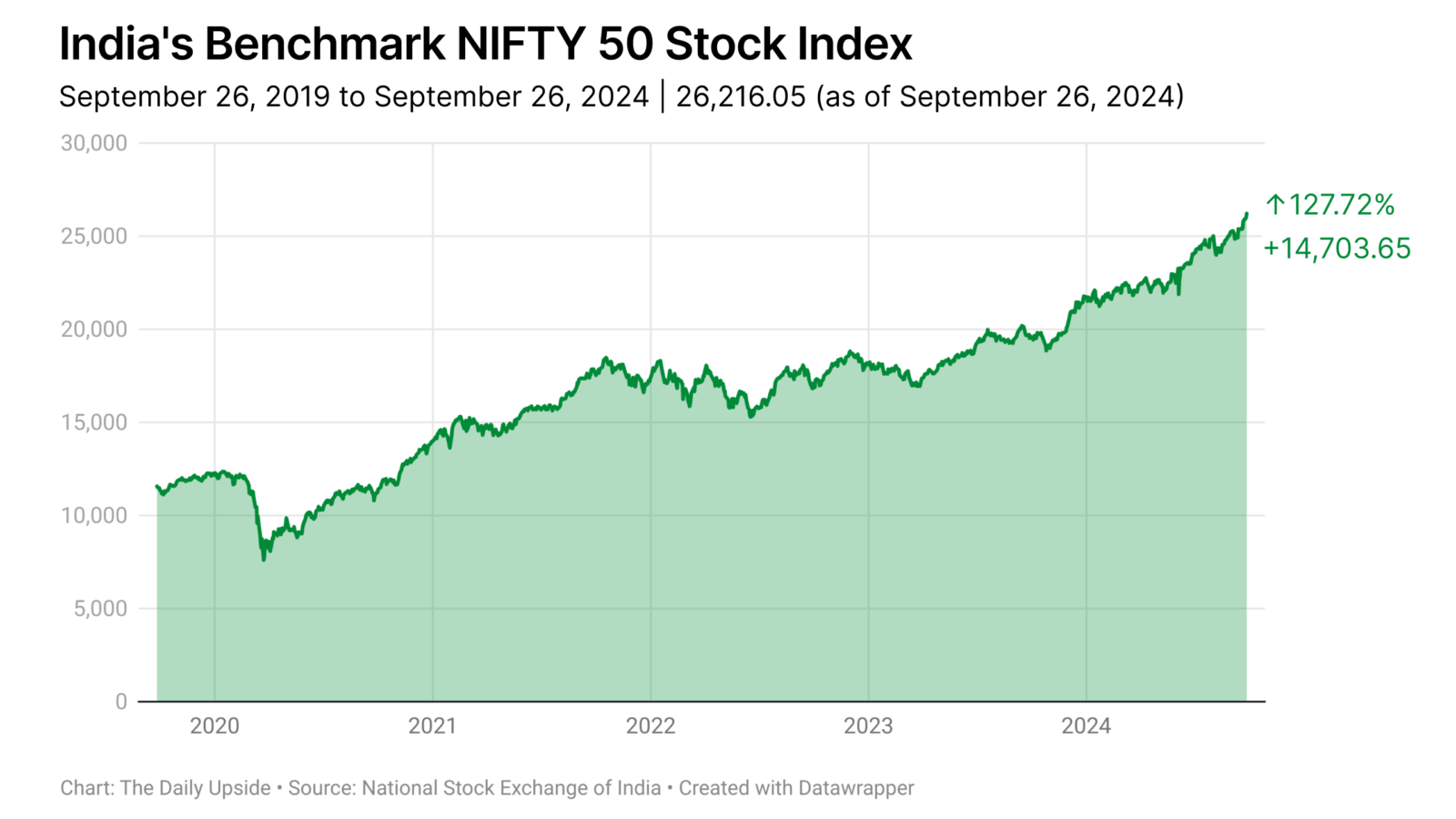

None of this is to say retail investors haven’t had good reason to try their hand at the markets, or that they haven’t contributed positively to them in some ways. Since its low point in March 2020, India’s blue-chip Nifty 50 index has more than doubled to a total market cap of roughly $5 trillion. That’s outpaced the percentage growth of Europe’s top indexes, Japan’s Nikkei 225, economic rival China’s Shanghai Composite, and the S&P 500.

Initial public offerings are also on track for their best year ever: 50 IPOs have raised $6.4 billion in the first eight months of the year, already besting last year’s $5.9 billion tally. Among the major listings are financial services company Hero, logistics provider Ecom Express, and real estate developer Kalpataru. The average gain upon listing has been 35%, according to capital markets firm Prime Database.

“Strong returns in India have been primarily driven by domestic institutional investors and a surge in retail participation,” JPMorgan researchers noted in a report earlier this month. “Rising investor interest in India is starting to form a virtuous cycle of liquidity, sell-side coverage, investor participation and capital issuance.”

The market’s bull run has been buttressed by strong macroeconomic fundamentals that distinguish India from neighboring China, where policymakers have struggled in recent months to kickstart a slowing economy.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts India’s GDP will grow 6.1% over the next five years — and 7% in the 2024-25 fiscal year — supplanting Japan and making it the world’s third-largest economy behind the United States and China by 2027. V. Anantha Nageswaran, an economist who serves as the chief economic advisor to the Government of India, said last year that the country will sport a $7 trillion economy by 2030, double last year’s $3.5 trillion GDP.

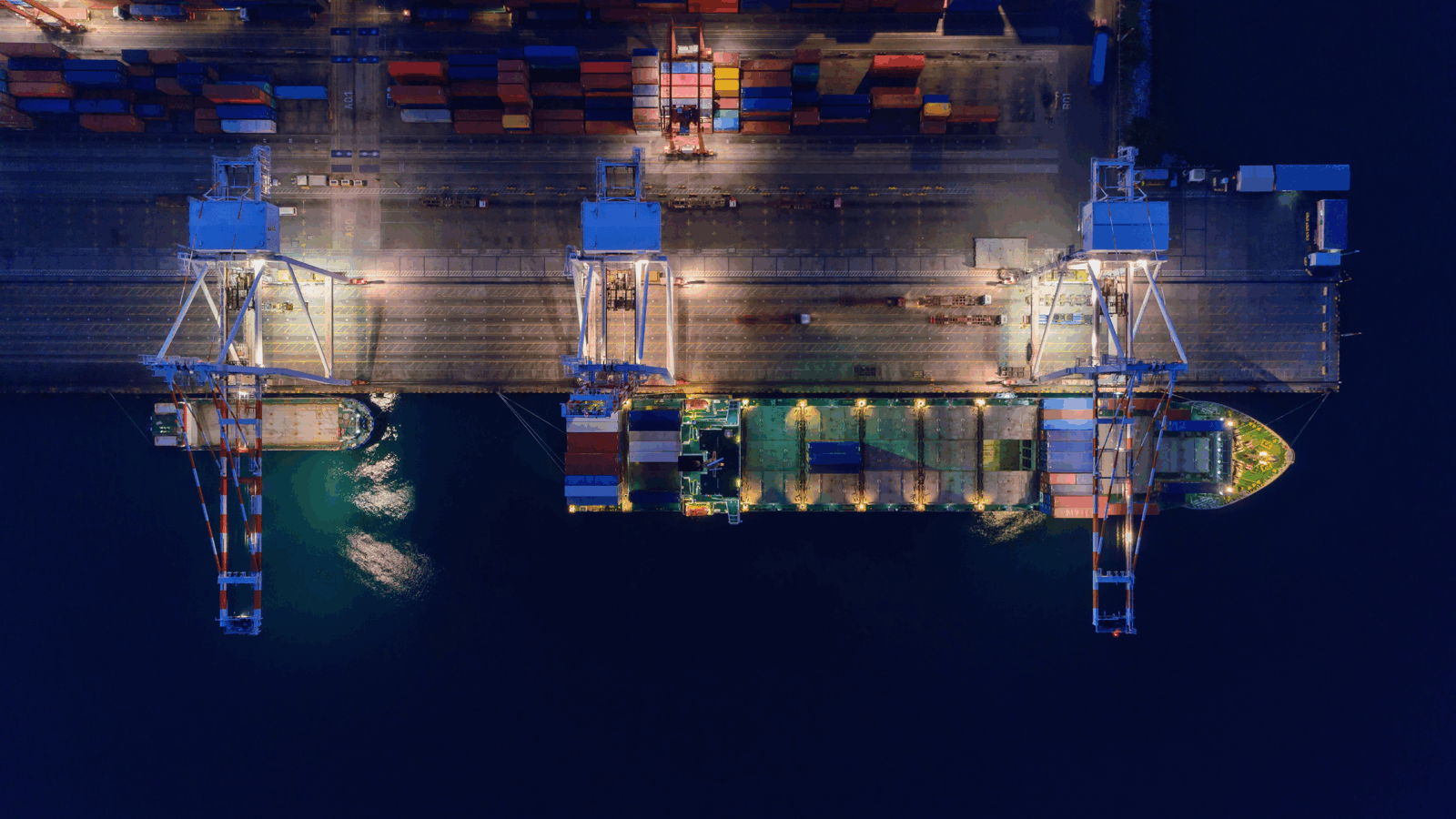

“The government has laid out ambitious plans for goods exports to hit $1 trillion annually by 2030, as the country hopes to become a top alternative for companies looking to diversify their supply chains away from China,” said JPMorgan analysts, who also noted manufacturing growth, long stagnant, has come to life.

Brakes on the Hype Train

Even with all the good news, there are signs that markets may simply have gotten too frothy.

Bloomberg News reported this week that the Nifty 200 index — “designed to reflect the behavior and performance of large and mid-market capitalization companies,” according to the National Stock Exchange of India — is currently valued at 24 times its 12-month forward earnings estimates compared to an average of 19 times over the last decade.

The publication also noted that corporate profits, which have driven up valuations, are primed for a slowdown: The earnings growth of the Nifty 50 is set to drop to 8.4% in the fiscal year ending March 2025, compared to 20% the year before, according to estimates by Kotak Institutional Equities.

Wary of overvalued securities, foreign institutional investors became net sellers of India-listed shares last month as net outflows topped $1 billion, according to SEBI data. Through August, the FT reported that year-to-date net inflows were just $2.6 billion, compared to $22 billion in 2023.

Analysts, too, have become more cautious: Over two-thirds of Nifty 200 stocks currently have “hold” recommendations, compared to a decade ago when buy and hold recommendations were split equally, according to a Bloomberg analysis.

Risky Business

The combination of a booming economy and a frothy stock market has left SEBI concerned about the risks for retail investors, who are likely far less equipped to deal with any sort of correction than institutional investors.

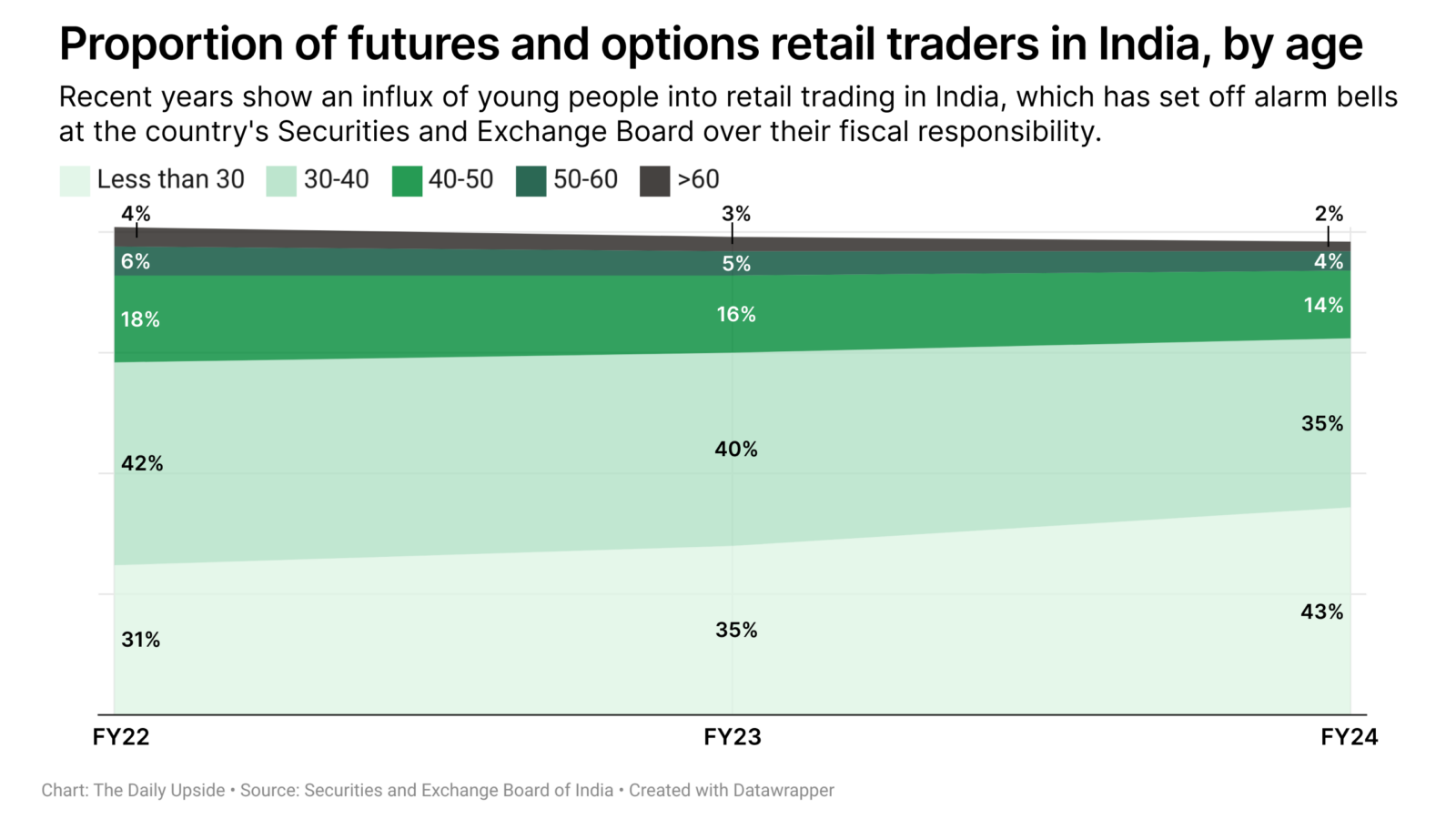

That is especially the case when it comes to futures and options (F&O) trading, which lets investors speculate on the price movements of securities. F&O trading has become wildly popular among India’s new class of retail investors.

Just how wildly popular? India accounted for 78% of equity options traded in the entire world last year, according to Futures Industry Association data, making Reddit’s notorious WallStreetBets and the speculative frenzy of retail traders in the US look like a drop in the bucket.

Gupta, Axis Bank’s mutual fund CIO, has notably dubbed this phenomenon “the gamification of Indian equities” — suggesting that new investors are throwing their money away to speculation as opposed to putting it in stable investment vehicles or working with professional money managers.

SEBI, meanwhile, released a report this week showing that retail investors in the F&O market are getting absolutely clobbered: 93% of them lost money over the last three fiscal years, with an average loss over that period of ₹2 lakh ($2,389).

A mere 1% of F&O retail investors made a profit of more than ₹1 lakh ($1,194) after transaction costs — and, even though almost all of them lost money, they spent an average of ₹26,000 ($310) on fees in FY24. Few seemed capable of learning any lessons, either: More than 75% of those who lost money in F&O the preceding two years kept on trading.

They also come from demographics at far greater risk than other investors, according to SEBI. A huge chunk of F&O traders are under 30 years old — 43% this year, up from 31% in 2023 — and almost three-quarters are from smaller towns. SEBI said 76% of the traders that had losses in FY24 reported under ₹5 lakh ($5,975) in income.

In July, SEBI chair Madhabi Puri Buch warned that household savings are being depleted by speculative bets and youth with virtually no savings are losing money.

“They have no understanding of the risks,” one senior executive at the Mumbai outpost of a foreign bank told the FT last month. “There’s a whole generation of people who have not seen a market correction, which is why we see a lot of people putting their savings in equities.”

In addition to its crackdown on finfluencers, SEBI is expected to debut a slate of reforms to protect speculative retail investors. A consultation paper in July floated several proposed changes, including increasing minimum contract sizes and requiring traders to increase their collateral.

Hopefully, they’re put in place before the young generation sees its first market correction.