With Dollar Reserves Running Out and Ratings Downgrades, Maldives Stares at a Crisis

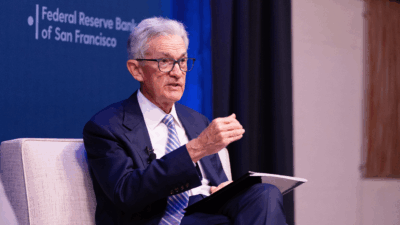

Fitch Ratings downgraded the debt of the Maldives for the second time in just over two months, suggesting it’s likely to default on bonds.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

In the latest chapter of “Paradise Lost,” Fitch Ratings downgraded the debt of the Maldives for the second time in just over two months Thursday, compounding pressure on the island nation’s bonds and suggesting the agency thinks it is likely to default.

Loan Shark Crosses the Indian Ocean

An Indian Ocean island nation of just 520,000, the Maldives has borrowed heavily from India, China, and private creditors to finance increasing deficits, even during the coronavirus pandemic when tourism — which accounts for nearly 30% of GDP and over 60% of foreign currency reserves — came to an effective standstill. The Chinese and Indian export-import banks now hold the majority of the country’s $3.4 billion in external debt.

That’s led to a suboptimal situation in which President Mohamed Muizzu, elected last year on a campaign to reduce Indian influence, has now had to negotiate with the country and China for debt relief. To avoid a default, the Maldives will need to address external debt of $557 million in 2025 and $1 billion in 2026. Both are more than the country’s vastly depleted foreign currency reserves, which Fitch noted fell 20% in July to $395 million. That’s the lowest since 2016, and rebounding may prove especially difficult:

- The Maldives’ sukuk, a form of debt under Islamic religious law, that’s due in 2026 fell to a record low of 70.24 cents on the dollar Thursday. At the start of the month, the bond traded at more than 80 cents.

- Even with planned tax hikes and austerity that includes ending indirect subsidies for food, electricity, and fuel, and even after Muizzu said The Export-Import Bank of China gave the “green signal” to defer five years of loan payments, his government may have to do more. Fitch said Thursday that “support from IMF or other multilateral donors would most likely be contingent on debt restructuring.”

Working Pains: The debt crisis has already spilled out into the lives of workers. Last year, the Maldives National Association of Construction Industry said contractors are funding projects on their own and billing the government, only to not be paid. Earlier this year, fishermen protested against the indebted state-owned fish exporter for not paying them.