Is Monetization the Final Frontier for the Commercial Space Industry?

As the ISS is decommissioned, several space station projects are in the works, but a business model may be the final frontier.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

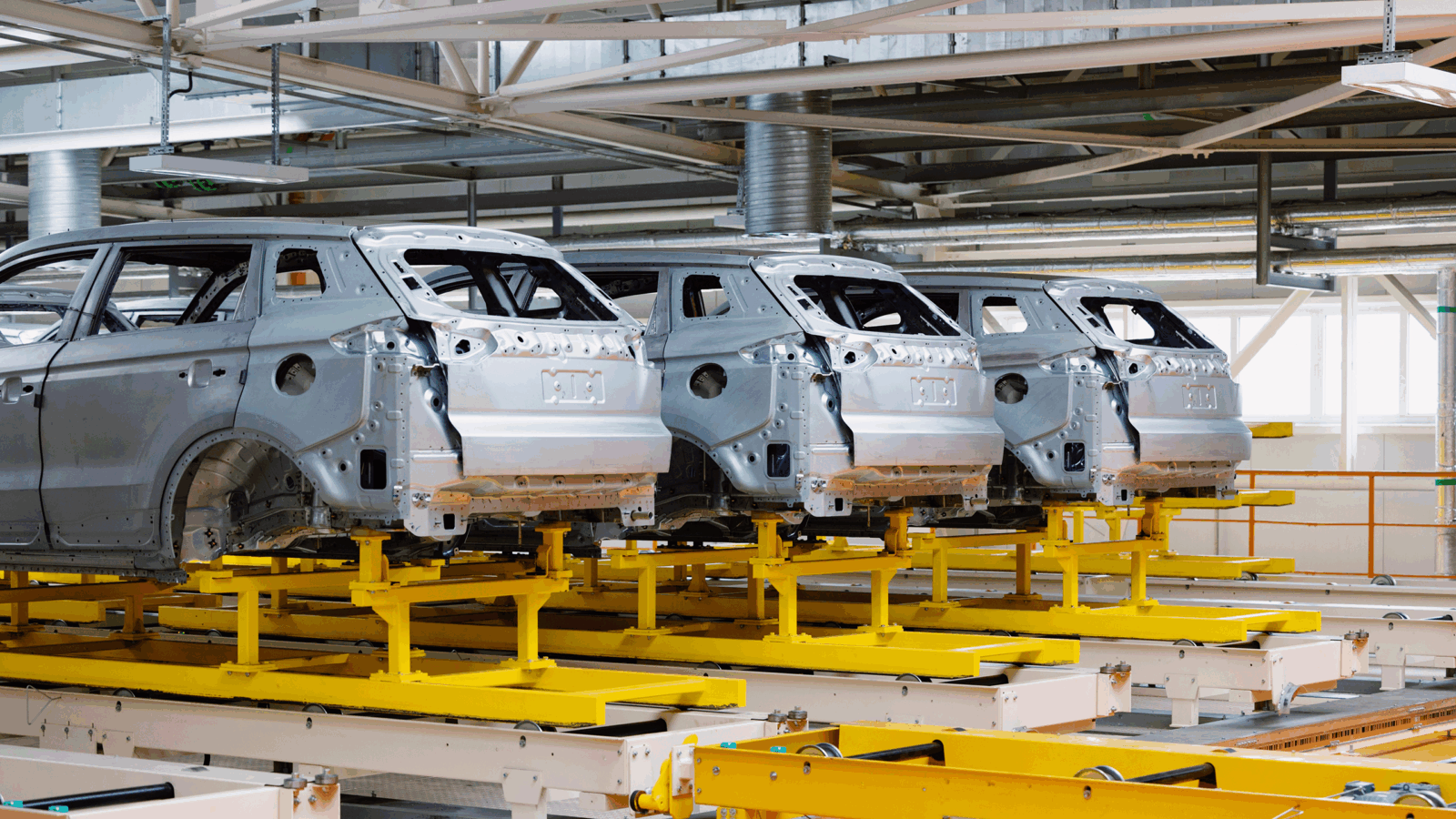

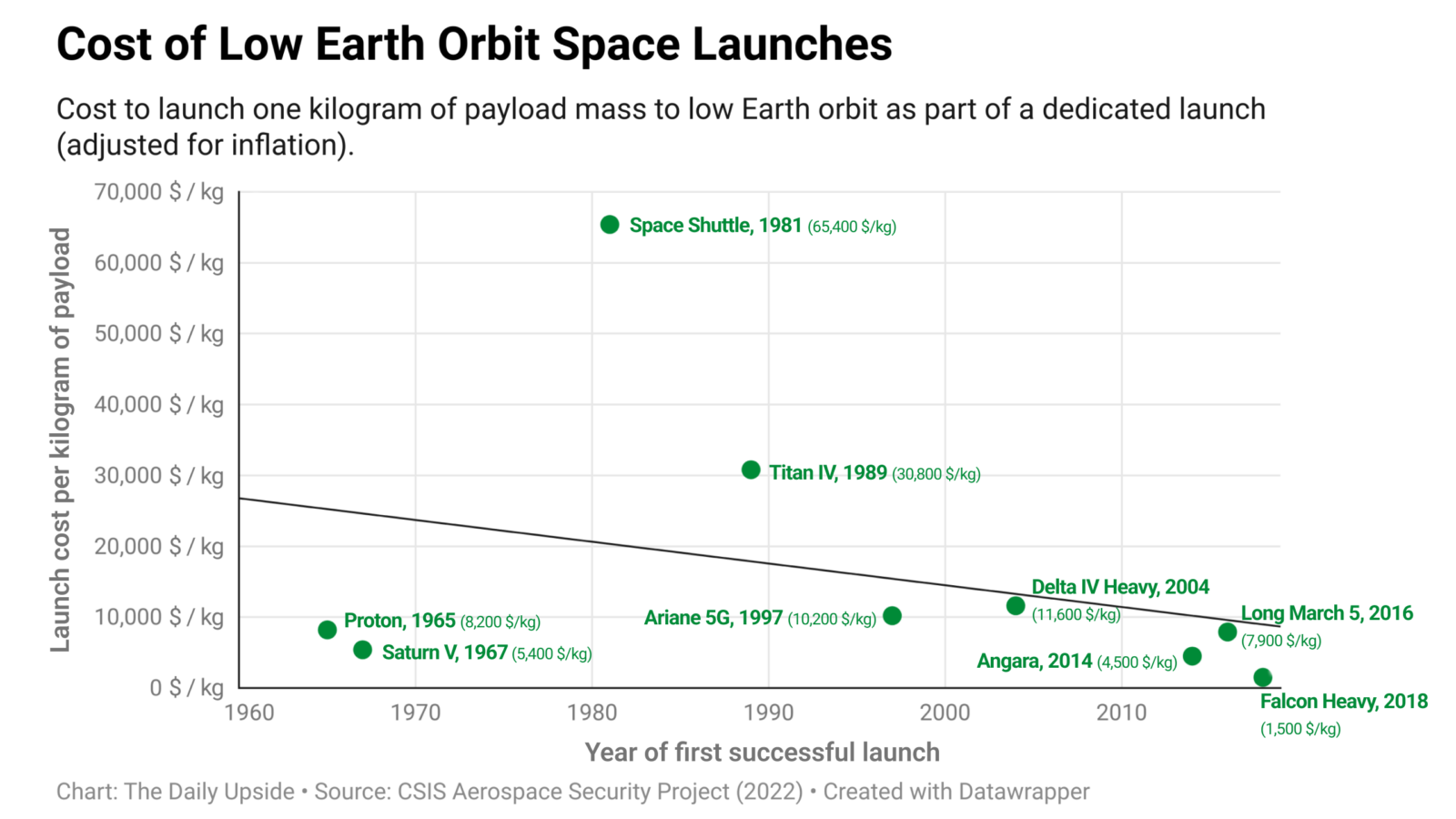

More and more of what happens on Earth depends on the space economy: Satellites facilitate our financial systems, tell us where to go, and provide us with life-preserving broadband so we can keep on scrolling through cat videos. Humanity’s initial forays into space were spurred on by geopolitics, but now the private space sector is booming. We’re pretty used to SpaceX launching rockets or flinging satellites into orbit, and the next chapter in the space economy is about to begin.

A small constellation of new commercial space station projects is due to go up as the ISS, a geopolitical vestige, is slowly decommissioned. But space stations are harder to monetize than satellites, and with the private sector growing bigger and bigger, attracting enough revenue outside of government contracts will be tough. “The market is the biggest challenge,” John Conafay, CEO at Integrate Space and a veteran of the private space sector, told The Daily Upside.

Cold Wars and Tide Pods

The ISS was hatched at the tail end of the Cold War by President Ronald Reagan, but construction didn’t start until 1998, and the first astronauts didn’t get there until 2000. By then, the Berlin Wall had fallen, and the ISS became a shining beacon of global cooperation in the heavens.

What the ISS has shown in the intervening years is that having a space station is very useful for research and development. The effects of microgravity allow all sorts of research that’d be impossible to replicate on Earth, including medical research, drug development, and, most importantly, R&D for a better laundry detergent (Tide signed a deal with NASA, which is in the market for a detergent astronauts can use in low-resource situations).

The Commercial Frontier

As the ISS reaches the end of its lifespan, several companies have announced plans to put commercial space stations into orbit before the decade is out. Let’s meet our contestants:

- Axiom Space, an aerospace company based in Houston, Texas, says it plans to launch the first section of its commercial space station project in 2026. To date, Axiom Space says it’s raised $505 million from investors and bagged $2.2 billion in contracts.

- Another project called Orbital Reef is being led by two companies, Blue Origin (Jeff Bezos’ space company) and Sierra Space. They say Orbital Reef should be up and running by the end of the decade.

- They’re not the only companies to couple up. Airbus Space and Nanoracks are working together on a space station called Starlab, targeting a 2028 launch with operations starting the following year.

- Possibly the most ambitious project timeline-wise is being led by Vast, which says it’s scheduled to launch on a SpaceX rocket “no earlier” than next year. Vast’s CEO and founder, Jed McCaleb, is best known for being the founder and CTO of cryptocurrency Ripple. In a 2023 court filing, McCaleb said he’s already committed up to $300 million of his personal wealth to Vast, adding: “To date, I have solely funded the enterprise and expect to continue to do so for the foreseeable future.”

They are all boldly going where no company has gone before. Dr. Jill Stuart, an expert in outer space governance at the London School of Economics, told The Daily Upside that space industry deadlines should always be taken with a grain of salt. “The timeliness on these things are always ambitious and frankly unrealistic,” she said.

SSaaS (Space Stations as a Service): Currently the private space sector’s biggest customer is the public space sector. A perfect illustration of this is SpaceX’s $843 million contract with NASA to decommission the ISS. “It’s not a dichotomy between commercial and government,” Stuart said. Agencies seem to be anticipating a deepening of that relationship when it comes to space stations. On the webpage for its ISS transition plan, NASA said it would be “one of many customers in a robust commercial marketplace in low Earth orbit where in-orbit destinations as well as cargo and crew transportation, are available as services to the agency.” The European Space Agency has also publicly tied itself to the Starlab project.

Space Markets

The price of space launches may have come down, but space stations are still a costly business. In the past, that was kind of the point. “The expense of space was almost a power move,” Stuart said. “But now you see different actors: countries, companies, that see the value in bringing the cost down.” Countries including India, Brazil, and the United Arab Emirates have been key in this space, according to Stuart.

So where can commercial space stations expect to get money, aside from housing space agencies’ astronauts? There are two official answers:

- Commercial R&D is a key selling point for commercial space stations. Conafay said we still haven’t seen an explicit case in which space research has achieved something impossible on Earth, but there’s already evidence that it might provide some economic efficiencies — for example, in drug development. For pharmaceutical companies, Conafay said, “space research tends to become a drop in the bucket.”

- Space tourism also gets a lot of mentions in business plans. In an April report McKinsey predicted that by 2035, space tourism will be dominated by commercial space station retreats for the ultra-wealthy, although the market itself will tap out around $4 billion to $6 billion.

There’s also a third big customer that’s always a major presence in the space industry, although it hasn’t been explicitly mentioned in the projects’ marketing materials: the military. Take a look at SpaceX’s Starlink satellite project as a template — its selling point was as a great consumer product, beaming down internet to remote parts of the world. But in the last two years — since it started operating in Ukraine and other war-torn regions — it’s taken on more and more significance as a military contractor. “Space is the ultimate high ground,” Conafay said. “It’s been absurd in the past … to think that you can have a space company without military and defense applications being in the mix,” he said, adding that a space station is in essence “a more capable, large satellite.”

But if commercial, potentially international space stations become tangled up in military contracts, what will that do to geopolitics? There are already laws governing how states and their companies can act in outer space. Stuart sees some various amendments and memorandums coming our way soon, spurred by the commercial sector’s desire to operate more freely: “Space is not free from red tape.”