Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

For more than half a century, China boasted the largest population on the planet. Yes, it did just recently get supplanted by India, but the Middle Kingdom’s population of 1.4 billion — hundreds of millions of whom are newly middle class — represents a massive and irresistible market for US multinationals. Cash flow catnip for the likes of Apple, GM, Tesla, and Nike.

But the political and military temperature is rising. The run-of-the-mill retaliatory trade wars and saber rattling that defined US-Chinese relations for years have evolved into a full-fledged geopolitical crisis. And the Chinese market — already difficult to navigate with its unique cultural, bureaucratic, and competition issues — is now bordering on inoperable for many US businesses.

So strap in and join us as we dive deep into the latest chess moves of this important geopolitical rivalry and unpack what’s at stake for the multinationals doing business in China.

First, a Quick History Lesson

After suffering through a “century of humiliation” from 1839 to 1949, defined by intense subjugation by Western powers, China successfully reinvented itself as the world’s factory floor in the post-WWII economy. By leveraging socioeconomic and demographic advantages, China built a 30% to 35% production cost advantage vs. the US thanks to cheaper labor, facilities, and input costs.

Beijing cultivated and executed on an intense desire for economic self-reliance, which has evolved into today’s model of “dual circulation.” Former Congressman and head of the Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition, Mark Kennedy, explained the mantra to The Daily Upside: “China wants to be less dependent on the rest of the world, but have the world more dependent on them.”

And by any meaningful measure, they have succeeded.

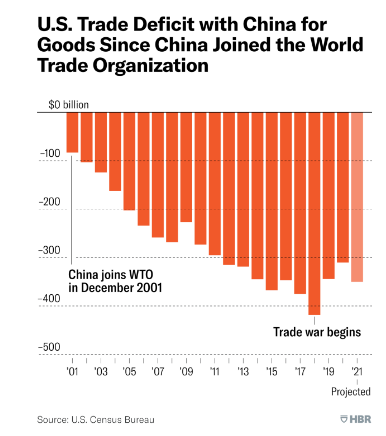

The US’ trade deficit with China eclipsed $400 billion in 2018. Today, Beijing is parlaying its manufacturing edge into technologically-intensive industries like artificial intelligence, semiconductor and aircraft production, and electric vehicles. Beijing is pumping $1.4 trillion into these initiatives through 2025.

The desire to flex its economic and military might overseas has also been paramount. Highly strategic is the Belt and Road Initiative, a global infrastructure development project launched in 2013, which many consider the centerpiece of President Xi Jinping’s foreign policy priorities. Beijing denies the initiative is motivated by geopolitical ambitions, but the scope of infrastructure projects suggests otherwise.

A vast network of port development projects, railways, energy pipelines, and a massive expansion in the use of China’s currency, the renminbi, are all on the punch list. To date, 147 countries have signed on to BRI-related projects, representing two-thirds of the global population. Estimates vary, but experts expect China will invest nearly $8 trillion into BRI initiatives.

China has also appeared keen to capitalize on a fluid geopolitical landscape to extend its influence:

- In the wake of the US’ withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Taliban agreed earlier this month to extend the Belt and Road Initiative to the Middle Eastern nation, causing many security analysts to raise alarm over China’s likely eventual influence over the country’s vast lithium deposits, which are critical for the transition to clean energy.

- Last month, Xi visited Vladimir Putin in Moscow where they had a “very productive” meeting to discuss a “new era,” a notion widely understood as a new world order where the US is no longer the single dominant superpower.

“China’s ambition is clearly to build a new world order with China in its centre,” wrote Josep Borrell, the EU’s high representative for foreign policy, in a letter to EU foreign ministers.

State Czar: For foreign businesses operating within China’s borders, the country’s policies have become increasingly hostile in recent months. The Wall Street Journal reported last week that Chen Yixin, China’s state security czar, has been tasked with a new and aggressive crackdown on overseas firms. Armed with China’s stringent anti-espionage laws, recent interventions have been both broad and swift:

- Earlier this month, authorities raided the offices of Capvision, Bain & Company, and Mintz – US businesses that Chinese authorities suspected of spying because they had allegedly been communicating with experts in areas such as government policy, national defense, and technology, the Financial Times reported.

- “If you’re a company that collects a lot of data, or allows individuals to express views, and are not willing to allow the government to have access to that data or to restrict free speech, you’re not going to be able to operate effectively within China,” Kennedy told The Daily Upside.

Within the financial sector, China is carrying out a sweeping crackdown on high-ranking domestic officials, with a definitive chilling effect on investor confidence. Dozens of officials have been placed under investigation, detained, or subjected to sanctions as Beijing’s anti-corruption officials are tasked with wrangling bankers who “neglect the party’s leadership.”

US Blowback

The backlash against China’s increasing economic coercion and flex of military might in the South China Sea is top of mind at the G7 meetings in Hiroshima this weekend. G7 members said they are “seriously concerned” about China’s increasing military aggression. Leaders from the US, EU, and Japan are collectively focused on “de-risking” relations with China, while being careful not to suffer economic blowback.

Stateside, pressure is mounting in Washington across a number of key hot-button topics from AI, to TikTok, to Chinese land ownership in the US.

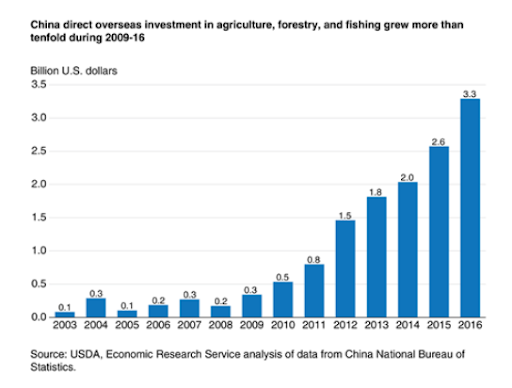

Earlier this month Florida governor and presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis signed a law to stop most Chinese citizens from buying farmland. While China’s ownership of US farmland is currently low (just 0.9% of all foreign-controlled farmland is China-owned), China’s agricultural investment in the US grew more than tenfold between 2009 and 2016.

“This is no small amount of food we’re talking about,” South Dakota Republican Rep. Dusty Johnson, told NPR. “In recent years the Chinese Communist Party has increased their holdings of foreign farmland … by 1000%. They own 1,300 agricultural processing facilities outside of China, and that number is growing rapidly.”

What Does it All Mean for US Businesses?

Suzanne Clark, president and chief executive officer of the US Chamber of Commerce, didn’t mince words in a recent speech. Clark claimed that Chinese policies and practices “in pursuit of China’s absolute security…have made the world less secure.”

Indeed, China’s clear prioritization of an expansive state security apparatus ahead of even its own economic interests marks both a clear ideological shift from recent history. For foreign operators, the risk involved in having employees and capital in China continues to rise, a reality which caused foreign direct investment into China to fall 48% in 2022, according to Chinese data.

No one understands the risks and opportunities associated with doing business in China more clearly than Apple. Unlike fellow tech giants Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, and Alphabet which have relatively low exposure to China, virtually all of Apple’s hardware is made in China. The company employs just 14,000 people directly in China, but through manufacturing partnerships with companies like Foxconn, Apple has insight into 1.5 million workers in its global supply chain, the vast majority in China, according to the FT.

During the pandemic, Apple was forced to cede significant control and oversight of its Chinese operations. Sources familiar with Apple’s operations told the FT that Apple’s ability to send US engineers to monitor the company’s Chinese operations has become significantly limited, hindering Apple’s ability to drive innovation and risking leaks of intellectual property.

For Apple, that has put a new thrust behind the desire to diversify manufacturing operations. The tech giant manufactured just 1% of iPhones in India in 2021, but that number has crept up to nearly 7% today. It’s a high-wire act for Apple CEO Tim Cook, but one he is properly compensated for.

“The Cupertino guys stood back and let the Chinese take the lead,” one source told the FT. “The Chinese guys completely control the product now.”