El Niño Ravages Land and Sea, Slamming Markets

Climate change is colliding with another phenomenon called El Niño – and the results are already far-reaching, global, devastating.

Sign up to unveil the relationship between Wall Street and Washington.

As the Atlantic Hurricane season ends, the U.S. braces for El Niño.

Climate change is colliding with another phenomenon called El Niño – and the results are already far-reaching, global, devastating.

So far: Worldwide sugar prices sprinted to a nearly 13-year high, as crops in Asia languished in unseasonably dry weather. Top sugar exporters India and Thailand have been particularly hard hit, while nations like Nigeria (which needs sugar to make bread, typically a cheap source of nutrients for millions of people, but not anymore), are producing less, causing heightened food insecurity.

Data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows that the world has less than 10 weeks of sugar in reserve. And as India is reining in its sugar exports to safeguard its own supplies, spiraling prices have compelled other countries, such as Indonesia and Kenya, to pull back on their sugar imports.

Meanwhile, China has been forced to release sugar from its reserves to offset soaring prices for the first time in six years.

None of these developments bode well for the easing of inflation, amid the supply chain issues of the pandemic and the wars in Europe and the Middle East.

“As climate change continues to supercharge our weather, the impacts on natural climate phenomena like El Niño become increasingly significant,” said Australia’s Climate Council, an independent, evidence-based organization, observing some of the hottest temperatures on record in Sydney in September and “catastrophic fire conditions” on the New South Wales south coast.

Speaking to Power Corridor, Matthew Warnken, climate entrepreneur and managing director at AgriProve, a New South Wales soil carbon project developer, says that El Niño instantly brings a sense of dread to farmers and cattle ranchers in the region. “It is absolutely front of mind and a chill goes through farming,” he says, noting that many are battling dry weather conditions and bush and forest fires. “There’s this overwhelming sense of, it’s going to get worse, based on how quickly the heat has come, how quickly things have dried out.”

Warnken added, “It impacts farmers’ outlook and confidence. Unfortunately, these cycles can be multiyear, which can only amplify the uncertainty. The rains are very welcome, but there’s a feeling that it’s just temporary and it’s going to dry out again.”

While El Niño is a naturally occurring phenomenon, its effects are greatly amped up by climate change, Warnken noted, “adding another layer of uncertainty” for Australia’s farmers and ranchers.

In Peru, the rising temperatures of ocean waters due to El Niño has hurt fishing hauls, with some high-value varieties, such as tuna, simply vanishing. And the impact of a record-breaking drought in the Amazon rainforest, exacerbated by El Niño, could stretch well into 2026. The Amazon’s vegetation has dried up, spurring thousands of fires that have damaged more than 11 million acres, while the Amazon River has fallen to its lowest level in more than a century.

For others, the fallout isn’t just about higher temperatures and rising prices – it’s about life and death. In Somalia, more than a million people have been displaced by flash flooding and heavy rains due to El Niño’s extreme weather and more than 100 people have died. Its Horn of Africa neighbors, such as Kenya and Ethiopia, are also contending with fatal floods, which are worsening the region’s ongoing humanitarian crisis affecting millions of people following the fiercest drought in four decades. (The Horn of Africa is a spot to watch, as it is a lightning rod for the extreme weather patterns linked to climate change.)

All this, as world leaders meet this week at the United Nations climate summit in Dubai to discuss the long-term future of the planet, how to raise billions of dollars to support poorer nations in the climate transition – and, possibly, even decide on the fate of fossil fuels. (Although the latter idea seems unlikely, as The New York Times reported this week the talks are already “consumed by intense debate” over the phase-out of fossil fuels, with the event’s president, oil executive Sultan Al Jaber, suggesting there is “no science” behind the notion that the burning of oil, gas and coal are heating the planet.)

The climate talks, which continue through at least mid-December, have drawn a lot of boldface names, among them U.S. President Joe Biden, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, World Bank President Ajay Banga, European Union Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra and China’s climate representative, Xie Zhenhua, in addition to U.N. Secretary General António Guterres and a passel of power brokers, business executives, oil lobbyists, climate change activists and nonprofits.

The summit began on Nov. 30, the same day the U.S. concluded its Atlantic Hurricane season, which brought 20 named storms – a larger than normal amount – fueled by El Niño’s record-warm sea surface temperatures. An average season has 14 named storms, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The agency noted the 2023 hurricane season ranked fourth for the most named storms in a year since 1950.

The current El Niño season is forecast to continue well into spring 2024, with the greatest impact yet to come in North America. “I think we’ll see the effects further into the winter and the spring,” says Scott Patterson, a senior meteorologist for San Francisco-based ClimateAi, which uses artificial intelligence and proprietary software to model climate forecasts for the agriculture industry.

“California usually gets a lot of rain, we may see that develop as we get more into the winter,” in addition to more rains in the southwest, Texas and the southeast, he tells Power Corridor. “It can also mean a cooler spring, so that might affect crop production and, in the northern U.S., it could be drier and warmer.”

The effects of El Niño, which only comes every two to seven years, serves as one of the world’s best-known examples of how tiny temperature shifts in far-flung places can lead to years of droughts and floods, with fatal outcomes.

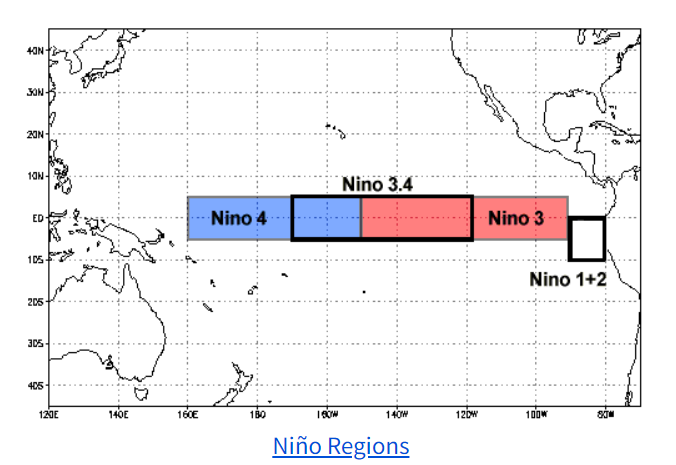

Way out in the equatorial Pacific Ocean is a well-defined zone (see graphic below) measured by meteorologists called “the Niño 3.4 region.” An El Niño event occurs if the sea surface temperatures rise above normal by 0.5 degrees Celsius or higher – and right now, they are more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above normal, marking a strong El Niño, according to the NOAA.

“It seems so remote, but a small change far away can have an enormous impact,” says Johnna Infanti, a meteorologist with the Operational Prediction Branch of the NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

“Changes in the tropical Pacific atmosphere can have chain reactions across the globe,” she tells Power Corridor. “Shifts in the jetstream, shifts in the storm track can really impact climate patterns in a way you wouldn’t expect. It’s why I got into meteorology.”

Drawing from the NOAA’s forecasts, Infanti says this year’s El Niño is seen bringing above-average temperatures to the northern U.S., especially the northeast, northwest and Alaska, going into spring 2024. At the same time, above-average precipitation is projected for the southern U.S., particularly in the southwest and southeast.

While the potential for extreme weather events in the U.S. remains uncertain, “El Niño favors stronger hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific basin, and we do see a strong jetstream, so there is an elevated chance of heavy rainfall and more energetic storms in the southeast,” says Jon Gottschalck, chief of the Operational Prediction Branch at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

El Niño is expected to continue through the Northern Hemisphere’s spring, with a 62 percent chance of lasting through April-June 2024, the NOAA predicts.

How does Wall Street plan on handling the potential volatility? Very carefully, says Rostin Behnam, chairman of U.S. futures market watchdog the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. In October, he spoke at a conference about how the agency would be closely watching any developments, noting that past El Niños resulted in heightened global inflation and roiled both agricultural and energy prices.

“El Niño years are known for downpours, droughts and threats to crop yields and pricing,” he warned, adding, “We have long recognized that extreme weather events and climate impacts manifest in our markets directly, indirectly, and in feedback loops in every asset class.”

Traditionally, investors aren’t in the business of juggling bets around potential weather events – changeable as they are – until they become extreme events.

“People are really hesitant to place bets based on event risk,” one market participant who runs a New York commodities desk at a major bank tells Power Corridor. “Right now, most people are in a ‘Show Me’ mode. Their feeling is, ‘I’ll trade on it when it happens.’ El Niño is a weather risk event, so it could happen, or not happen.”

“You also see this with how the market bets on the outcomes around decisions by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, or the Israel-Hamas war,” he says. “And don’t forget, we’ve been betting on an Iranian war for 25 years – and it hasn’t happened.”