Why This Year’s Black Friday Matters

It’s official: 2023 has been the year of the American consumer. The propensity for Americans to spend as though they have bottomless bank accounts has bolstered U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) growth all year and catapulted the nation back on…

Sign up to unveil the relationship between Wall Street and Washington.

American spending saved the economy this year – but what about 2024?

It’s official: 2023 has been the year of the American consumer.

The propensity for Americans to spend as though they have bottomless bank accounts has bolstered U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) growth all year and catapulted the nation back on its pre-pandemic track.

Whether Americans can keep up the feverish rate of spending into Black Friday, the holiday season, or the 2024 presidential election cycle is another matter, however.

CEOs, economists and market participants are keeping close watch on the trendlines. “Consumers are still spending, but pressures like higher interest rates, the resumption of student loan repayments, increased credit card debt and reduced savings rates have left them with less discretionary income, forcing them to make trade-offs,” Target Chief Executive Brian Cornell told analysts in a call last week.

While a smattering of retailers have issued cautious and even glum fourth-quarter outlooks – including Best Buy, Nordstrom, Dick’s Sporting Goods, BJ’s Wholesale Club and Abercrombie & Fitch – surveys in recent weeks have indicated the potential for record holiday spending.

According to a new survey this month from the National Retail Federation and Prosper Insights and Analytics, 182 million Americans are planning to hit the shops during the five-day span between Thanksgiving and “Cyber Monday,” with expenditures expected to hit record levels in November and December. Specifically, holiday spending is expected to be up 3 percent to 4 percent from last year, totaling around $960 billion.

It’s not just about spending on holiday gifts – it’s about taking the temperature of the broader economy and gauging whether America has dodged the recession bullet.

Around this time last year, economists were sounding dire warnings of a virtually unavoidable recession in 2023. In one case, Bloomberg prognosticators not only forecast higher chances of a recession “across all timeframes,” but put the likelihood of a recession by late 2023 at 100 percent. At the time, it said, “The forecast will be unwelcome news for [President] Biden, who has repeatedly said the U.S. will avoid a recession and that any downturn would be ‘very slight.’”

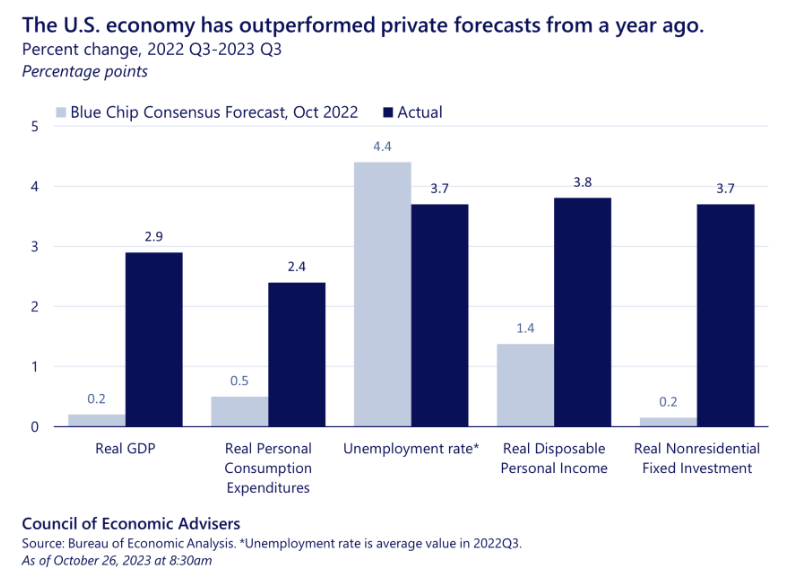

In a recent note from the White House poking fun at that prediction, the Biden administration noted that, “over the last four quarters, real GDP has grown at a healthy 2.9 percent, far surpassing the consensus 0.2 percent growth projected last year” (see chart below).

Aggressive, almost gravity-defying U.S. consumer spending has been this year’s “biggest surprise in the performance of the economy since this time last year,” says the White House, as real consumption spending leapt 2 percentage points more than expected a year ago to 2.4 percent versus 0.5 percent as of late last month.

Real consumption spending, which is the inflation-adjusted amount of money spent by U.S. households, represents two-thirds of the U.S. economy. That gives shoppers a lot of power over what happens next.

A big driver of this spending surge has been $11.6 trillion in aggregate compensation received by U.S. workers in an economy that boasts not only an extraordinarily strong labor market, but an influx of what the White House calls “prime-aged” workers, whose participation in the labor market hit a 20-year high this year.

Nonetheless, the labor market remains tight, generating a 3.8 percent increase in Americans’ disposable income, up from the 1.4 percent increase forecast, it said.

The result of all this spending? The U.S. has regained most of the ground it lost over the course of the pandemic, according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, which says the country “has seen a particularly strong GDP recovery and is on track this year to reach the level that would have been predicted by the pre-pandemic trend.”

Big picture, Treasury says, “most advanced economies are below the trend growth path that they were on before the pandemic, except the United States,” including the UK, Canada, Germany, France, Italy, the Euro area and Japan, many of which were affected by the Russian-led war on Ukraine. “U.S. inflation has cooled sooner and more quickly than in other advanced economies,” it said.

And yet none of the above puts to rest concerns about a recession in the not-too-distant future. “Many risks to the U.S. outlook remain,” Treasury says, including tighter credit, persistent uncertainty over government funding and ongoing strikes. (To be sure, the same prognosticators at Bloomberg recently warned a recession is “still likely – and coming soon.”)

Add to that the fact that U.S. consumers’ pandemic savings have very likely run dry and most surveys show the wave of spending that kept the American economy aloft this year is unlikely to keep up at this clip.

Overall, American households have been spending more and saving less, with credit card debt shooting past $1.08 trillion this month – the biggest increase since 1999 – even as higher interest rates make the cost of borrowing more expensive, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Campbell Harvey, a professor of finance at Duke University, who has been looking very closely at how Americans are saving and spending, says this year’s holiday season could be an important indicator of what’s to come, as consumer spending represents roughly 70 percent of GDP.

So far, the data appear to point to a slowdown ahead, he tells Power Corridor. “Delinquencies on credit cards and automobiles have turned up,” he says. And even without those delinquencies, record-breaking credit card debt alone shows consumers’ spending power is weakening. “It’s kind of obvious that if you had the savings, you would spend that and not put it on a credit card,” he notes.

That combined with the rising cost of borrowing and servicing debt and the return of student loan repayments means economic growth might not only slow, but turn negative heading into the New Year.

“In 2024, the consumer is not going to be leading the economy as it did in 2023,” Harvey says.