Britain’s Legacy of Leaving the EU

The UK is heading for its first election since it actually left the EU, but what has Brexit done to Britain’s economy?

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

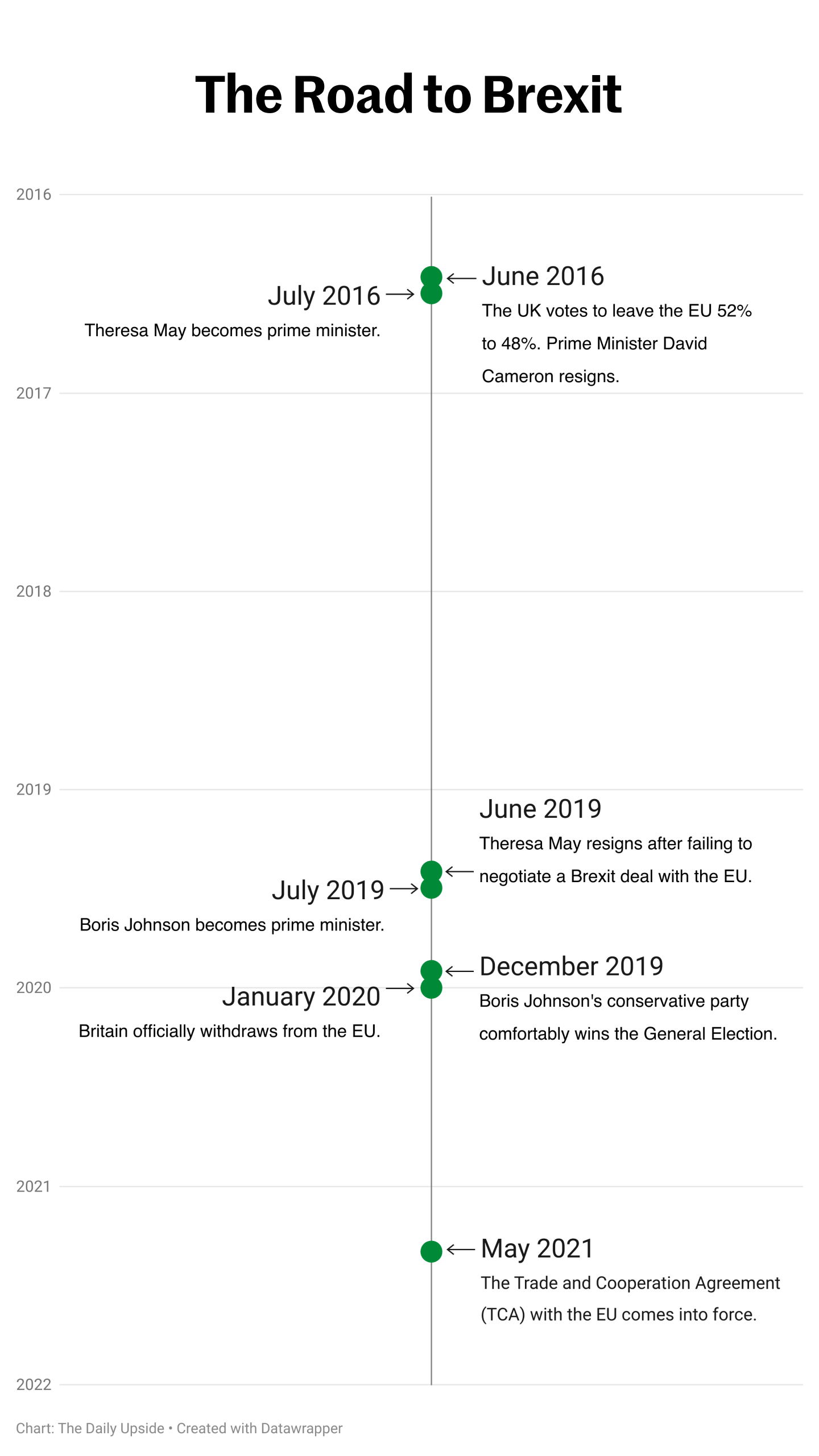

Brexit was fated to lose the spotlight early on: Just as the country was bracing for whatever upheaval leaving the EU might bring on January 31, 2020, the pandemic swooped in. Now four years and a lot of economic shocks later, economists have begun to figure out what exactly Brexit has done to the UK economy — and just how many (if any) promises made by the Vote Leave campaign have survived.

Trading With Places

Before 2020, the UK’s inclusion in the EU meant it was part of a single European market — a system where goods, services, and people could cross borders with minimal paperwork. That was a huge facilitator for trade, but a big selling point for Brexit proponents was the idea that, free of EU constraints, the UK would strike a series of independent trade deals. Thomas Sampson, an associate professor at the London School of Economics specializing in international trade, said that part of the plan isn’t going so well.

“The whole idea of global Britain conceptualized as a pivot towards trade outside of Europe was a flawed idea to begin with,” Sampson said. Since leaving the EU, the UK has struck three trade agreements with Australia, New Zealand, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (a coalition of countries on the Pacific Rim). Unfortunately, these deals are merely a drop in the ocean. “The trade deals are not that ambitious […] and they’re kind of dwarfed by the effects of leaving the single [European] market,” Sampson said. Here are the numbers:

- The Office of Budget Responsibility has projected that Britain leaving the EU will mean its long-term productivity takes a permanent 4% hit.

- In contrast, the OBR’s assessment of the new trade deals with Australia and New Zealand is that they might add something like 0.04% to GDP — it had previously pegged the figure at 0.1%, but revised it down in November 2023.

Sampson said replacing the EU, the UK’s biggest trading partner, is just a huge task.

“The scope for gains from deals with people outside the EU was always going to be much smaller than it was for deals with the EU,” he said. “You can’t solve that problem. Trade economists refer to that as the gravity problem, the idea being: You trade more with things that are big and close by, and the EU is big and close by. You can’t defy gravity in that way.”

He added that Britain also is fighting a growing geopolitical trend against new trade deals. “[The UK has] been trying to do these trade deals at a point in time when the sort of shift in geopolitics has been away from free trade and towards kind of more skepticism towards free trade agreements,” Sampson said.

Recalcitrant Revolutionaries: The UK’s biggest target for a trade deal would be the US, its second-largest trading partner after the EU. Striking a new deal could make the import and export of goods flow even more freely, increasing volume, but according to Sampson the US has been uninterested. “It’s all about domestic politics in the US,” Sampson said, adding: “[the Biden administration is] concerned that past trade deals have had negative effects on middle income manufacturing workers, and therefore has adopted more protectionist policies. Stuff that has nothing to do with Brexit at all, but because of it, they don’t want to do deals.”

While Britain has been trying to make friends elsewhere, its exports to the EU have dropped around 20% since the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) with the EU came into force in 2021, Sampson said, and imports from the EU have dropped by about 25% relative to the rest of the world. Sampson described Brexit’s effect on international trade as a “net negative,” although he said it’s not been quite as bad as some economists — including himself — once feared.

Migration Seesaws

The Vote Leave campaign’s slogan was “Take Back Control,” and one of its biggest platforms beyond trade was immigration. It was a promise that Britain would control its own borders, and while it didn’t expressly say it wanted to drive immigration levels lower, it did list “out of control” immigration as a downside of remaining in the EU.

Ironically, since leaving the EU, Britain has actually seen record-breaking net migration:

- Net migration for 2022 was 735,000, and the latest official figures for the year to June 2023 show a slightly lower net migration of 672,000.

- That’s still way higher than pre-pandemic figures. In 2019 net migration clocked in at 184,000.

But the higher totals aren’t about Europeans continuing to come to the UK. Rob McNeil, deputy director at the University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory, said that EU citizens were put off migrating to the UK as soon as the vote eight years ago came in. “This began in 2016, this was people responding to a message more than it was people responding to a law,” he said. Per the Migration Observatory’s data, EU emigration to the UK dropped 70% between 2016 and 2022. McNeil said that in addition to national sentiment, potential immigrants saw the value of the pound plummet in the wake of the referendum, making the UK less attractive to any EU citizens interested in sending money back home.

So, how has the UK ended up with an unexpectedly high number of new immigrants? McNeil cited two factors that have nothing to do with Brexit: pent-up migration that followed the end of covid-era travel restrictions, and big influxes of people from Ukraine and Hong Kong. Other contributing factors are policy changes brought in by former Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s administration that significantly liberalized the system for non-EU immigrants. McNeil said worries about a lack of low-skilled workers prompted the government to lower the thresholds for non-EU immigrants.

“For 500 million people, it was made much harder to come to the UK. For the remaining 7.5 billion, it became somewhat easier,” said McNeil, adding that the income threshold for non-EU immigrants was lowered as was the education-level requirement, to high-school diploma from university degree. He said that the UK government also actively encouraged foreign students to apply to UK universities (handily subsidizing those universities with above-average tuition fees) and solicited non-EU foreign workers to fill labor gaps in the social care sector.

What Goes Up… Doesn’t Necessarily Come Down That Much

McNeil said he expects net migration to decline slightly from its current “artificial spike,” but it’s hard to know where it might level out. It’s also exceptionally hard to work out what exact economic impact the migration spike has caused, and McNeil cautioned that the data is not easy to work with. But certainly some sectors have voiced concerns, including hospitality, which blames Brexit for a dearth in foreign workers. But, McNeil said, migration policy always results in “winners and losers.”

Regardless of actual economic impact, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has started to throw the car into reverse, clamping down on immigration and raising thresholds for would-be immigrants. However, his political message has largely focused on illegal immigrants coming in small boats across the English Channel, and McNeil doesn’t think Sunak’s actual or potential changes will have a huge effect on net migration. “These [policies] are the slightly kind of tinkering around the edges,” he said.

So that’s the Brexit legacy that’s left for Sunak to untangle: a contributor to extraordinarily high migration and a net loss (if not a totally catastrophic one) for British trade. Against a backdrop of an inflation crisis, new data saying that at the end of 2023 the UK went into a technical recession, and a Conservative ruling party that has torn itself apart over the last eight years to the point where ex-Prime Minister David Cameron, the man who stepped down after losing the referendum, is now back in government, it all seems like a less-than-ideal result.