Is China’s Export Economy Starting to Slip?

The world’s factory is slowing down and it might have nothing to do with the tariffs promised by the Trump 2.0 administration.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

The world’s factory is slowing down and it has nothing to do with Trump 2.0.

On Tuesday, data released from China’s General Administration of Customs Bureau showed that the country’s export business grew just 6.7% in November compared with a year earlier. That’s down from October’s 12.7% growth, and lower than the expectations of experts who predicted a rush of exports ahead of the incoming US presidential administration’s much-ballyhooed tariffs. The export slump suggests Beijing may be grappling with larger issues than any tit-for-tat trade spat.

Deflation Nation

China’s export industry has not been top of mind for Beijing leaders this year. They’ve been preoccupied instead by a major slump in the property market and sagging domestic consumption that have had the country on the edge of a deflationary spiral. On Monday, China’s National Bureau of Statistics announced that consumer inflation in November fell to just 0.2%, marking a five-month low. That triggered Beijing to loosen its monetary policy stance — from “prudent” to “moderately loose” — for the first time since the end of the global financial crisis 14 years ago. In other words: If China isn’t in crisis mode yet, it’s certainly in crisis prevention mode. Tuesday’s stats provided more evidence of anemic domestic consumption; imports decreased 3.9% in November, more than the 2.3% dip in October.

But it’s the slowdown in exports that might be more concerning. With China now facing pressure on both sides of the import-export equation, some experts are starting to ask the big question: What if the export-dependent economy can’t grow its exports anymore?

- China accounts for roughly 30% of global manufacturing, far outweighing its 15% share of global consumption. As Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for Asia-Pacific at Natixis, told the Financial Times this week, that means the rise of protectionism in Western nations could be especially harmful to China.

- Beijing has set out to increase trade with the Global South as a hedge against Western protectionism. But according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of government data, Tuesday’s figures showed that the growth of exports to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, China’s largest trading partner, slowed to just 14.9% year-over-year in November, down from 15.8% in October (trade to the US actually remained relatively flat, growing around 8% in October and November each).

China will still flirt with a record full-year trade surplus of $1 trillion, but 2024 could mark a turning point. “I think we’ve hit the peak of the traditional manufacture-and-export model,” Yao Yang, the director of Peking University’s China Center for Economic Research, told the FT.

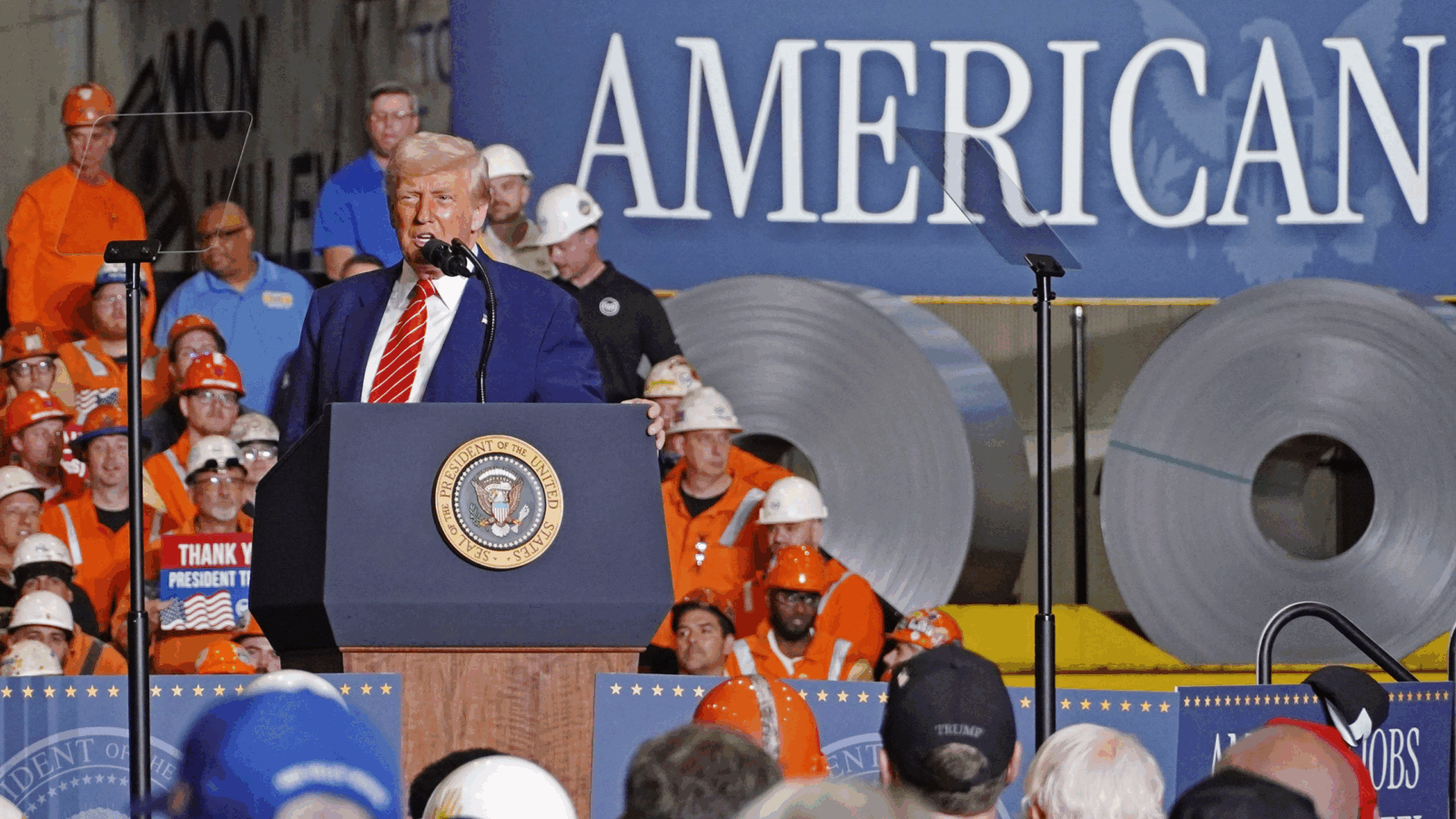

Trump Trade: Then there are the tariffs. How big? On the campaign trail, President-elect Donald Trump promised tariffs as high as 60% on Chinese goods, but more recently he has threatened levying tariffs of just 10%. Beijing has indicated it will do whatever it takes to reach its 5% GDP growth goal in 2025 — including raising its initial budget deficit target to an all-time high of 4% of GDP.