Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

Fourteen years ago, they were dubbed the “white knights,” riding to the rescue of global financial markets amid the greatest liquidity crisis in decades. They also walked away with billions in profits.

When predatory subprime lending, excessive risk-taking by global financial institutions, and the bursting of the U.S. housing bubble conspired to create the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, the richest monarchies of the Persian Gulf stepped up.

They bought stakes in western lenders like Citigroup and Barclays, even the odd soccer team (Manchester City) or department store (Harrods), and injected billions into capital markets through their sovereign wealth funds at a time when liquidity was drier than the Arabian Desert.

If anything, the profile of these Gulf-based sovereign wealth funds, whether the Kuwait Investment Authority or the Saudi Public Investment Fund, has grown since the 2008 financial crisis. So, too, has their ambition. Today, you’re as likely to see a Gulf fund in the press releases of a hot new tech fundraising round as a prestigious Silicon Valley venture capital firm.

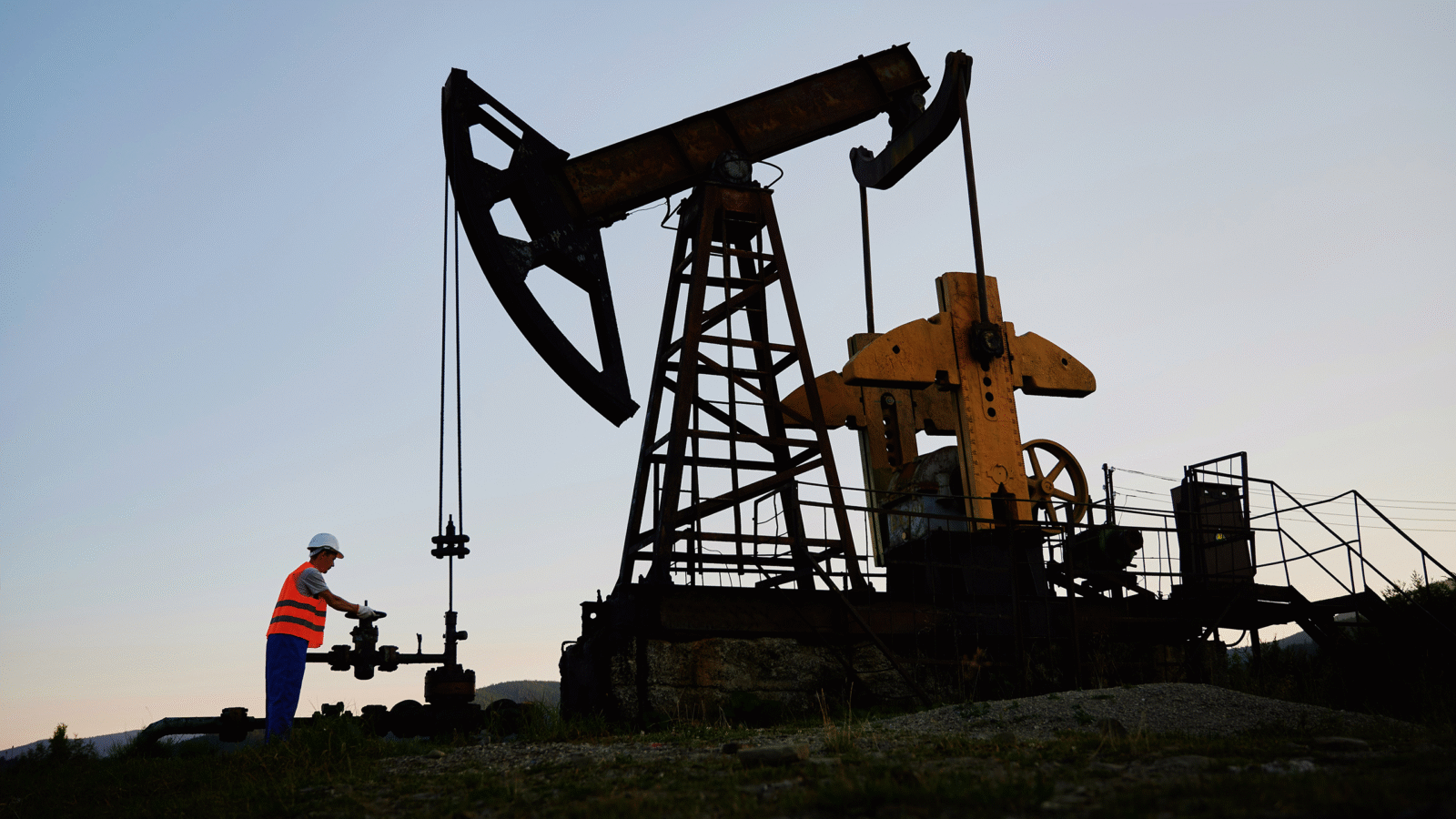

And with cheap cash in short supply once again — and with crude prices at their highest in memory — the Gulf’s sovereign wealth funds are taking more calls than the switchboard at a 1980s celebrity telethon. Just like in 2008, they have embarked on a spending spree and are poised to pick undervalued or depreciated assets – and make a pretty penny off of them when markets rebound.

From Sovereign Wealth to Spreading the Wealth

So what, exactly, is a sovereign wealth fund? Basically, it’s any state-owned investment fund that gets its money from a government money pipeline. That could be a country’s surplus reserves or excess resource revenues, or foreign currency holdings.

They invest that money with the goal of creating bigger savings for their country, which can in turn fund social and economic development or be used to stabilize the economy against volatility or inject capital during crisis times. Not the kind of stuff your average Sand Hill Road VC outfit tends to worry about.

Arguably the most famous sovereign wealth fund is not in the Gulf or anywhere in the Middle East: the Norway Government Pension Fund Global, which the Northern European country established in 1990 to invest surplus revenues from oil trading, has few peers. The Oil Fund, as it is commonly known, now has $1.2 trillion in assets (about $230,000 for every Norwegian) and, on average, holds 1.3% of the world’s listed companies, making it arguably the most powerful shareholder on earth. With apologies to The Beatles: isn’t it good, Norwegian wealth?

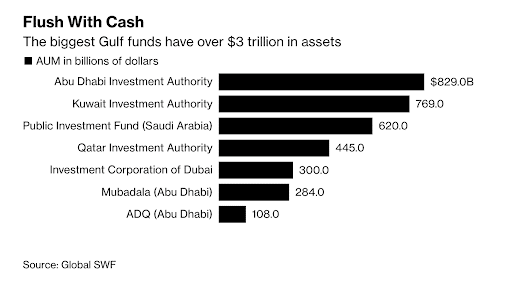

Magnificent Seven

According to sovereign wealth fund tracker Global SWF, the seven largest sovereign wealth funds in the Gulf region have over $3 trillion in assets among them. They are the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority ($829 billion), the Kuwait Investment Authority ($769 billion), the Saudi Public Investment Fund ($620 billion), the Qatar Investment Authority ($445 billion), the Investment Corporation of Dubai ($300 billion), and Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala ($284 billion) and ADQ ($108 billion).

The Gulf funds were already in the process of shifting their strategies from overseas deposits and securities to buying major stakes in companies before the 2008 financial crisis. But it was the Great Recession that turbocharged that transformation by offering the chance to snap up assets on the cheap, and did they ever take advantage:

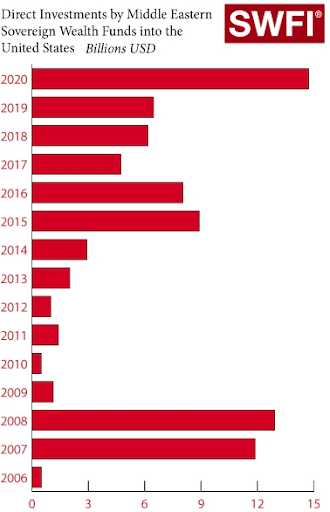

- According to the European Investment Bank, the number of foreign direct investments by Gulf Cooperation Council Sovereign Wealth Funds rose 540% from 15 in 2006 to 96 in 2009.

- This included a number of investments that rescued Western banks at the height of the subprime mortgage crisis, with Gulf sovereign funds bailing out Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, UBS, Merrill Lynch, and others with roughly $40 billion worth of investments.

Growing Gulf

The payoff from these investments was soon evident. In December 2009, Kuwait’s sovereign wealth fund booked a $1.1 billion profit on a $3 billion stake it took in Citigroup in January 2008, good for a 37% annualized return.

A few months earlier, in June 2009, the Abu Dhabi government’s International Petroleum Investment Company, sold a chunk of its investment in British bank Barclays, making a £2 billion profit on a £2 billion investment. In October 2009, Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund made a £600 million profit by selling a small part of its stake in Barclays (it would ultimately rake in £1.7 billion from its stake, which it exited in 2012).

“They didn’t panic into selling at the bottom of the market,” Mohamed El-Erian, the then-CEO of Pimco, told CNBC of the Gulf funds in 2009. “And now they can sell.”

In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Gulf funds made similar moves when markets dealt with the initial shock of lockdowns. Sovereign wealth funds based in the Middle East invested $14.7 billion in the US 2020, more than double the $6.5 billion they spent in 2019.

The New Pullback

Fast forward to today. This year’s economic pain hasn’t quite matched the punch of the 2008 subprime collapse, but it hasn’t exactly been a wrist-slap sailing either. Between the highest inflation in a generation, out-of-whack supply chains and battered energy markets thanks to Putin’s misadventures in Europe, the blows have just kept coming. And it shows.

After years of gains, stock markets are down — the S&P 500 has fallen 14% this year. After years of cheap cash and frenzied fundraising, global venture capital funding fell 27% year-over-year, to $120 billion, according to Crunchbase data. Meanwhile, at least 358 companies have canceled or postponed financing deals — including initial public offerings, mergers and acquisitions, bond sales, or loans — worth over $254 billion, according to Bloomberg data.

So who to turn to in this new down market? Gulf sovereigns of course, which have been empowered by the rising energy prices that are a symptom of the current downturn (Saudi Arabia alone makes nearly $1 billion every day from exporting crude)”

- The Gulf’s largest sovereign wealth funds have made no less than $28.6 billion in foreign acquisitions this year as of July 26, according to Bloomberg data, or 45% more than at the same point in 2021 and the most for any first six months on record.

- The new spin on this investment spree is that, after a decade expanding their portfolios, the low valuations and bargain targets they’re focusing on are in technology and health care — the Saudi Public Investment Fund has, in the years since the last downturn, become one of the world’s biggest tech investors through a $45 billion contribution to SoftBank’s Vision Fund (although the mammoth tech fund has stumbled badly, losing $27 billion in 2021 after a $37 billion profit one year earlier).

Stirred, Not Shaken

Among the wave of deals by Gulf sovereign funds this year is a $93 million investment by the Public Investment Fund in Aston Martin of Bond fame, boosting its existing stake in the British automaker to 17% as part of a $777 million rights issue.

One of the most active of the Gulf funds is Mubadala, led by Abu Dhabi’s ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed. The fund led a $400 million investment round in digital insurance company Wefox, agreed to a $3 billion deal to buy Swedish medical freight firm Envirotainer in partnership with EQT Private Equity, and came to the rescue of Klarna by leading an $800 million funding round in the struggling buy-now-pay-later firm after its valuation plummeted to $6.7 billion from $45.6 billion just months earlier.

“Sovereign wealth funds in the Gulf have become more sophisticated in their investment strategy and retain extensive global relationships,” Ayham Kamel, head of Middle East and North Africa at consultant Eurasia Group, told Bloomberg. “Current global market conditions also support the rise of the Gulf sovereign wealth funds as their oil surplus can be mobilized.”

Blood Money

It’s great to have a group of oil-rich state funds with seemingly endless resources ready to inject liquidity into markets at the drop of a hat every time there’s economic uncertainty, but there’s one difficult question for some — is it moral to take money from a state that does immoral things?

Chief among the concerns about the Gulf states in this area is Saudi Arabia. In 2018, a team sent from Saudi Arabia murdered Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the orders of Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the CIA determined. In addition to Saudi Arabia’s continued use of torture, supression of free spech, and widespread discrimination against women, Khashoggi’s death left many in Silicon Valley wondering whether the money is worth it.

“Any CEO should be concerned if they have a murderer among their investors,” Ali Partovi, CEO of VC fund Neo, told WaPo. “Your customers and employees are watching.” Investors also reckon with taking money from China, whose human rights record is less than pristine, though in neither case has the pontificating led to a reckoning – moral, financial, or otherwise.

It would seem that cash, at the end of the day, is king. Or sultan in this case.