The Brain Tech Business Keeps Getting Buzzier

The neural interface market is full of startups vying to put technology into the human brain, but which will actually make brains a business?

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

Any company led by Elon Musk tends to make headlines and Neuralink, which aims to implant computer chips into people’s brains via hair-thin electrode wires, is what headline writers dream about. After years of missed deadlines, the company is finally ready to start testing its neural interface technology on humans. But here’s the thing: Musk’s companies have succeeded when they’ve had the first-mover advantage, and the neural tech industry has been quietly maturing for decades. Similar tech is being designed by quite a few companies, a few of which are run by ex-Neuralink founders. So once scanning or stimulating our brains becomes more commonplace, what kind of market is there, and what will give one brain-chip company an edge over another?

In n’ Out Brainers

Neural interface technology already is used in some standard pieces of medical equipment or treatments. You’re probably familiar with cochlear implants, which stimulate the auditory nerve allowing deaf people to hear. Parkinson’s disease patients have been treated for quite some time with deep brain stimulation, which works by implanting electrodes into the brain that send out electrical pulses, helping people to regain motor control.

Neural interface tech companies want to take the technology even further. Prof. Andrew Jackson, a professor of neural interfaces at Newcastle University, told The Daily Upside that research into neural interface tech used to be split into two camps: one that uses signals from the brain to control some kind of external technology (e.g. a cursor on a screen) and the other uses technology to send signals into the brain, stimulating it.

With advances in technology such as AI data processing and ever-smaller semiconductors, however, it’s becoming more possible to merge both camps into a single device. For example, existing neural interface technology allows people with prosthetic limbs to control their prostheses using a chip in their brain, but now researchers are working on how the artificial limb might send signals back to the brain to restore the sensation of touch.

Getting Into the Brain Business

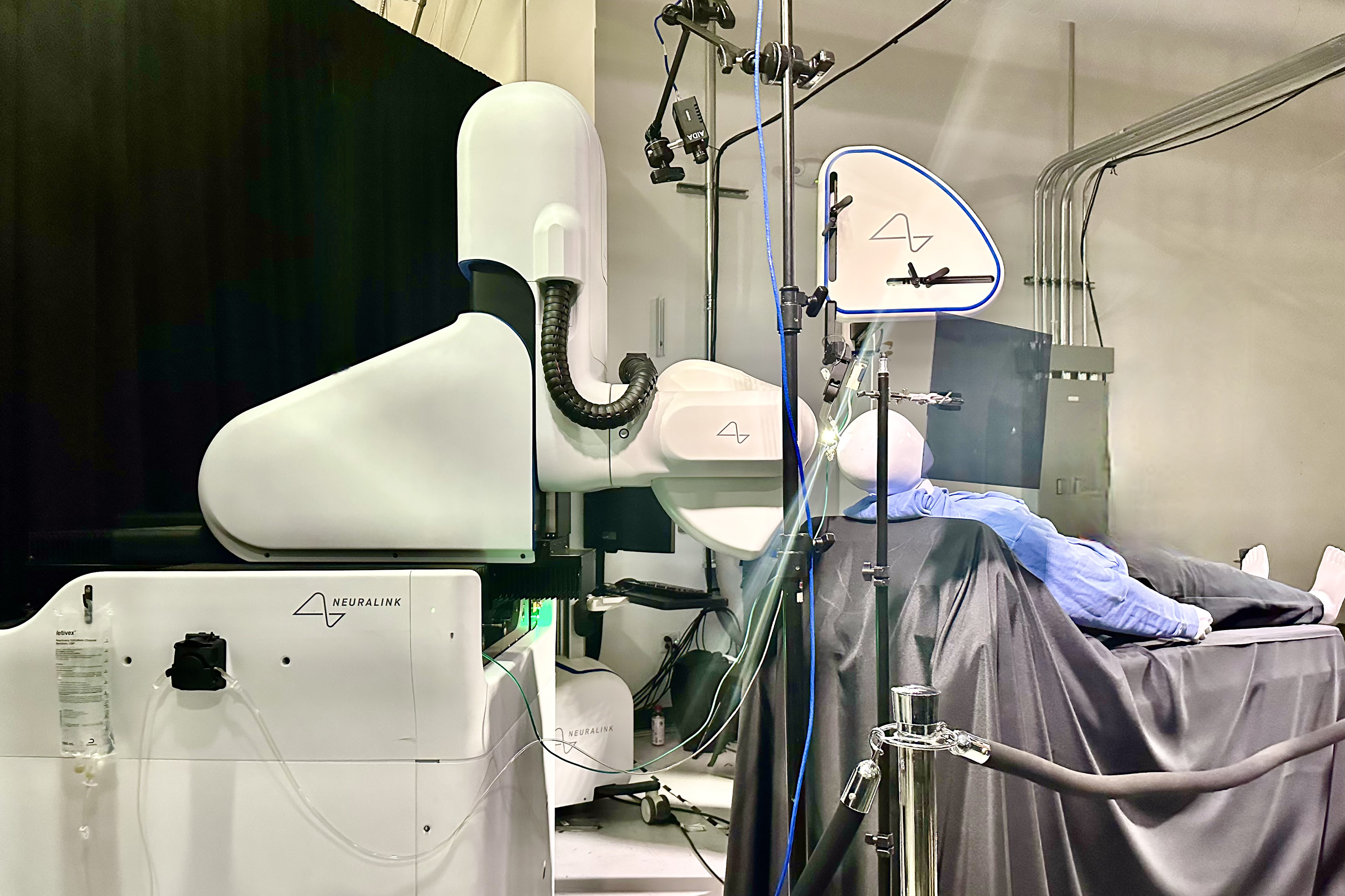

These startups trying to push the envelope on brain tech fall once again into roughly two camps — invasive and non-invasive tech. Neuralink, for example, uses the invasive tech of installing a chip that involves brain surgery. The company has even designed a robot to perform the actual installation once a neurosurgeon has removed a piece of the patient’s skull.

Non-invasive technology is less risky but also less powerful, as the signals coming from the brain are muffled by the pesky layers of bone and skin that make up the human head.

While Neuralink is excitedly advertising its first human trials, it’s still well behind a handful of companies — and according to Musk biographer Ashlee Vance at least two rivals are living rent-free in the billionaire’s head:

- Synchron: whose tech (the Stentrode) enters patients’ brains via blood vessels using a stent, implanted its first interface in a US patient last year and completed enrolment for its first US clinical trial. It also received a $75 million cash injection at the end of last year from investors including Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and former Neuralink president Max Hodak.

- Onward: a Dutch company that specializes in spinal implants to help people with spinal cord injuries regain mobility.

The stated ambitions of these companies — for the near future, at least — is focused on people with severe disabilities and impairments. Neuralink has said its first goal is to allow quadriplegics to control computers and mobile devices using their brain chips. Synchron’s Stentrode has already allowed people to do the same, and Onward has already seen some success in restoring movement to people with spinal cord injuries.

Consolidated Brains: Dr. Rylie Green, a professor of bioelectronics at Imperial College, told The Daily Upside that while the current generation of startups are essentially research vehicles, there are already four big, dominant players in the space — Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Livanova — who furnish patients with proven technology like deep brain stimulation. Green believes that as smaller companies prove their technology is viable, bigger industry fish will probably start hunting for tasty acquisitions.

Brainonomics

While the effect of these devices could be nothing short of miraculous for individual patients, Jackson said that for the economics of these commercial companies to work long-term, they need broader appeal. “[invasive technologies] will find applications in the more severe cases of injury or disability, I think there’s a slight problem, that those aren’t necessarily big enough markets to support the kind of investment that we’re seeing at the moment.” he said.

“The problem that we need to solve at the moment is that the current generation of interfaces are still quite limited,” he added. “So you can do things like moving a cursor around on a computer screen […] But for people with, say spinal cord injuries, they already have other ways that they can interact with computers. For instance, of eye trackers or sensors that are picking up movements that have been spared from the injury. So the devices need to work quite a bit better than existing technologies to be useful on a day-to-day level.” Jackson said the question of where to find a bigger market for neural interfaces is still unanswered. “It may be that the killer application hasn’t been figured out just yet,” he said.

Some less-invasive neural tech companies have marketed their products for consumers, rather than as medical tools. Neurable and Emotiv both sell electroencephalogram (EEG) headphones they claim help with concentration by monitoring brain activity. Even Apple has filed a patent for a similarly kitted-out Airpod, but Jackson doesn’t see the consumer space for neural interface tech going much further. “For control of actual computers, the signals are not going to be that great. You wouldn’t want to drive your car along a fast motorway with the car just being controlled by EEG signals from your headset,” he said.

For medical purposes, Green said she thinks non-invasive tech could tap into a huge patient base that isn’t well-suited to invasive solutions — dementia patients. “There is a huge potential there for a much bigger market. Because what we often forget in this space is the people we’re trying to implant in are often very old. They’re often people who are fragile and who can’t take on surgeries, and brain surgery is not going to be the best idea for them,” Green said.

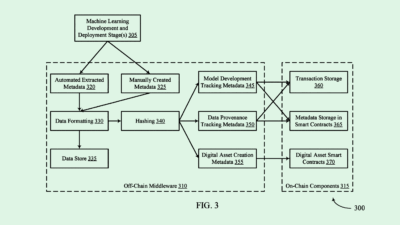

A USB-C for Brains: Green also believes a good industry standard for neural interface tech would be “plug and play” components, i.e., tech that can easily slot in with other companies’ products. “Previously all have the workup and now it’s all been, you start with a condition you design a device around how to fix that specific condition,” she said. “That’s great, but it puts you in the Apple scenario where you have to buy all the accessories and everything that goes with that one device.”

Neural Tech’s Alexa Moment

For Jackson, the exciting scientific frontier lies in figuring out just how similar (or different) our individual brains are. “I think the really interesting question is: To what extent can we build decoders to infer things from the brain that generalize across people?”

He views the current decoding capabilities of neural tech as similar to where speech recognition was in the 1980s — when you personally had to sit and tell your computer all the words you specifically might want to say to it. “But if anyone else came into the room and started speaking to it, it would fail because it had been built to understand your voice,” Jackson said.

Compare that to today, where Siri and Alexa can understand just about anyone who talks to them (albeit not quite as well if that person has an accent). Jackson said not getting to an equivalent point would present a huge limitation for the industry. “It seems to me to be a practical constraint on our vision of where neural technology could take us, if it turns out we can’t do that, and anyone who wants to use their Neuralink or whatever other brain implant has to sit there thinking all the things they might want to think when using this thing, and calibrating this in the old school speech-recognition way.”

If Alexa for your brain sounds like a wild notion then just remember: Jeff Bezos is an investor in Synchron.