As the U.S. Speeds Toward Default, Why the Pentagon Matters

The Pentagon leads U.S. discretionary spending – but for more than three decades, it has never once passed an audit.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

America is now entering an 11th-hour critical phase of the debt-ceiling fight in Washington. If Congress and the White House cannot cobble together a deal by June 1 – less than two weeks from now – the U.S. Treasury made clear again this week it will run out of funds to pay the nation’s bills and America will, for the first time in history, go into financial freefall.

This absolutely cannot happen, especially as the country struggles with a post-pandemic recovery, higher borrowing costs and searing inflation.

A default at this time would not only be a black eye from which the U.S. would never fully recover, not just in terms of how other nations see us, but also for America’s hanging-by-a-thread credit rating. It would amount to a financial and political götterdämmerung of unknowable proportions.

Because the fallout would be so dire, Americans can expect, in the days ahead, to be deluged with emotional bombast from both sides, the White House and Congress, Democrats and Republicans, if a deal is not swiftly cemented. There will be lofty, panicked verbiage, with very low visibility in the signal-to-noise ratio. (For those who would like a primer on what this battle is all about and the rising stakes, please see Power Corridor issue from earlier this month here.)

Until the final moment, both sides appear determined to engage in a high-tensile public messaging mano a mano of “the other side is holding America hostage,” which apparently is the only thing they are able to do, if they’re unwilling to compromise on a deal to raise the U.S. debt ceiling.

The U.S. government has already reached its current debt limit of $31.4 trillion and is relying on some fancy footwork in the form of special accounting maneuvers to buy it some final days before its funds run out.

What do other nations do? With the exception of Denmark, no other modern democracy imposes a hard limit on debt (and Denmark’s is so high, it never reaches it.) Maybe we should consider that. But then, of course, we couldn’t fight about it.

Over the weekend, labored talks that began last week between President Biden and congressional leaders stalled, but they resumed this week with Biden indicating just before leaving for a Group of 7 meeting in Japan, “I think you can be confident that we’ll get the agreement.”

He plans to return Sunday, with his team in constant contact with congressional leaders in the meantime to arrive at a deal. Speaking from the Roosevelt Room in the White House’s West Wing, Biden emphasized the meetings were focused strictly on the budget, not on avoiding default – something he has claimed he will not negotiate on, even as U.S. House Republicans conditioned raising the U.S. debt ceiling on $4.5 trillion of spending cuts to government programs.

“To be clear, this negotiation is about the outlines of what a budget would look like, not about whether or not we’re going to pay our debts,” Biden said. “The leaders all agreed, we will not default. Every leader has said that.”

In the U.S. Senate, Republican Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said he was heartened to see the talks between President Biden and Republican House Speaker Kevin McCarthy moving forward, although blamed Biden for the late start. “Because it took the president three months to start dealing in reality, we now have a time problem,” he said.

House Republicans only narrowly passed the bill to raise the debt ceiling, in exchange for spending cuts, less than a month ago. The legislation is not expected to pass the Senate and Biden said he would veto it, but it did provide a baseline for McCarthy and House Republicans to push for the talks.

While threatening to drive the nation into default over the debt ceiling is objectively nuts (I think reasonable minds can agree on this), thoughtful conversations about how the U.S. approaches its spending are definitely worth consideration.

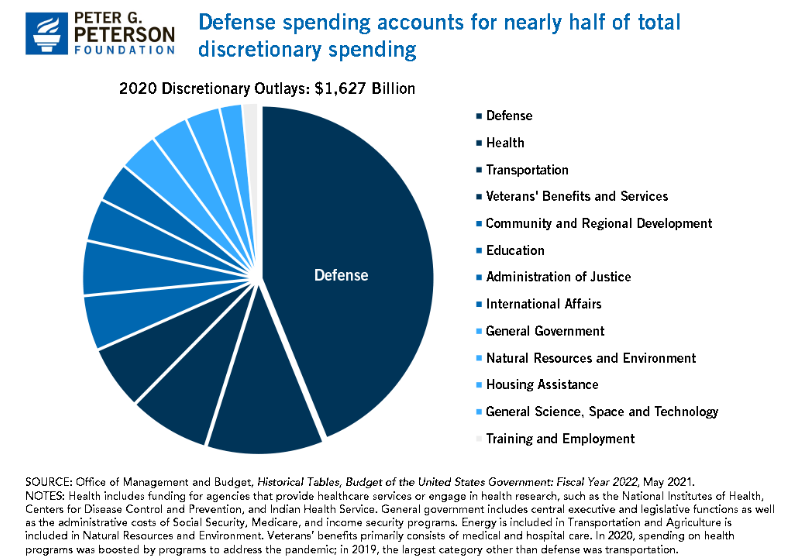

Let’s briefly review. The mêlée over spending in Congress is tied to U.S. discretionary spending. The lion’s share of this goes to the nation’s defense budget, which represents approximately 44 percent of discretionary expenditures. The rest goes to a wide range of other priorities, all of which are fractional compared with what the U.S. spends on the military.

Of these, the biggest chunks of cash go to health, transportation and veterans’ benefits and services. After that, narrower slices go to education and community and regional development, among others. (See pie chart below for one of the best, most recent breakdowns.) Natural resources and environment, housing assistance, and training and employment take up the smallest allocations of discretionary spending.

While any discussions of U.S. discretionary spending should rightly examine each category above for improvement or waste, military spending is, by far, the biggest offender, not just in size but in its appalling lack of transparency.

Why? To date, the Pentagon has never passed a single audit. While Congress passed a law in 1990 mandating all federal agencies provide regular, audited financial statements, the Pentagon, for m0re than three decades, has never been able to sufficiently account for its spending.

“I would not say that we flunked,” U.S. Department of Defense Comptroller Mike McCord said late last year, when the Pentagon was forced to admit it failed its fifth audit in a row. “The process is important for us to do, and it is making us get better. It is not making us get better as fast as we want.”

In its latest audit, the Pentagon, which must undergo 24 stand-alone audits for all its DoD reporting entities, plus one consolidated audit, could only account for 39 percent of its $3.5 trillion of assets.

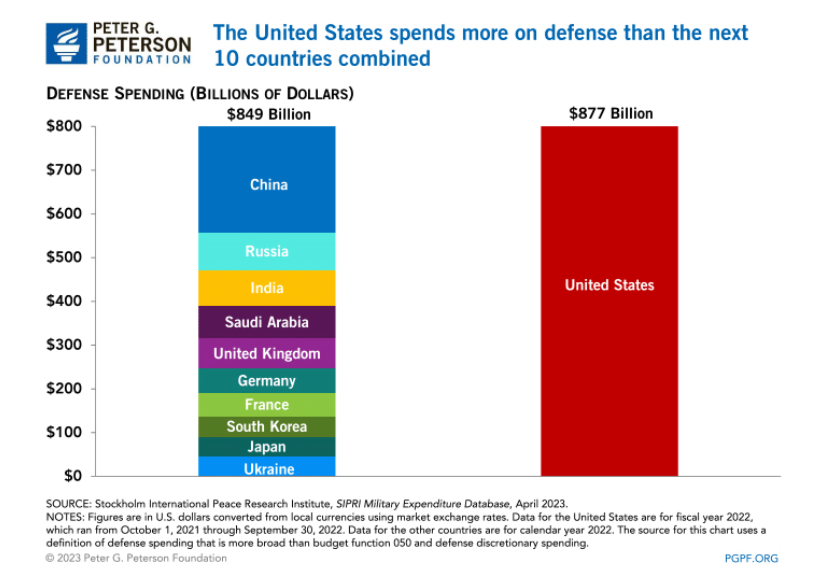

Notably, the U.S. spends more on its national defense than China, India, Russia, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Ukraine, Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Japan – combined – according to the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, which supports reducing the national debt. The eponymous group was set up by the co-founder of New York asset manager Blackstone.

The Pentagon’s spending and accounting problems trace back years, with lawmakers and their aides pointing out it lost track of how many people it employs and even the location of all its buildings in the U.S. long ago. Speaking on background, one senior aide bemoaned in 2021, “It’s absolutely insane and I think it would shock a lot of people.”

Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates, who worked in the Obama administration, lamented, “If the Department of Defense can’t figure out a way to defend the United States on half a trillion dollars a year, then our problems are much bigger than anything that can be cured by buying a few more ships and planes.”

Yet in the current spending fight, congressional Republicans have made clear they will not consider trimming defense spending at all, “which means that everything else in annual appropriations, from cancer research, to education to veterans’ health care, would be cut by much more,” according to Shalanda Young, director of the nonpartisan U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

If defense spending was left untouched at the baseline level of just above $880 billion for fiscal 2024, all other programs would, by dint of the “simple but unforgiving” math, have to be slashed by 22 percent, said the OMB, which is tasked with providing non-political and neutral analysis.

Interestingly, there is greater bipartisan support for reducing military spending than most other parts of the discretionary budget. For instance, McCarthy, while pleading with House Republicans over the speakership in January, agreed to be open to reining in military spending.

Former Acting Defense Secretary Chris Miller, who served in the last months of the Trump administration, went so far as to recently publish a book pushing for close to a 50 percent reduction in military spending. “I think we have an opportunity to come home, rethink, retool, rearm [and] reinvest,” he said at a recent event publicizing his book. “We need to take a neo-isolationist stand right now and reduce our commitments overseas. I think we are strategically overextended.”

If there is a default in June, the effects would be immediate, hurting America’s most vulnerable. If the funds run out, it would shut down crucial government programs and spending, including health benefits, military funding and Social Security checks, in addition to roiling the stock and bond markets and putting millions of Americans out of a job.

On Thursday, the Bipartisan Policy Center said that as of June 1, the U.S. government is scheduled to make $10 billion in military, retirement and other payments; $12 billion in veterans’ benefit payments: and $47 billion in Medicare payments.

Ironically, the debt ceiling battle is already damaging the nation’s defense budget and national security, according to ranking member of the House Armed Services Committee Rep. Adam Smith, a Democrat from Washington. “Providing for our nation’s defense is the most important responsibility that Congress has been tasked with under the U.S. Constitution,” he said in a statement May 9 that made plain his concerns.

“There is no way to make the substantial cuts to discretionary spending the Republican majority is vaguely proposing without doing great harm to the defense budget and the national security of this country,” he said, urging Congress to raise the debt ceiling. “It is way past time to end these games.”

Usually around this time of year, Congress is busily working on the National Defense Authorization Act and getting the defense budget ready for the next fiscal year. But the debt ceiling fight has halted that too.

“When you lose time…no amount of money can buy back time,” noted U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin.

He added, “I would point out that [China] is not waiting. They will execute on their own timeline…Our budget is directly linked to our strategy. And of course, if we don’t have a budget, we can’t effectively execute that strategy.”