Deep-Sea DNA Is Becoming the World’s Buried Treasure

Bioprospecting for genes of new species in the world’s oceans has become complex and extremely lucrative.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

Roughly 70% of the Earth’s surface is covered by ocean, so it gets its own economy. The “blue economy” comprises any economic activity in the seas — fishing, shipping, and deep-sea mining. Fisticuffs are commonplace as international jurisdiction is somewhat murky. But the deep sea holds a bounty that’s been steadily growing and increasingly dominated by just a handful of countries — and even fewer companies.

Marine genetic resources, i.e., the DNA of every sea creature that scuttles, paddles, and squelches in the ocean, are hugely commercially valuable. And it’s just a handful of companies slapping patents on those naturally occurring genetic codes for use across a variety of industries: from cosmetics to agriculture to pharmaceuticals, and beyond. For the last 15 years, the UN has bickered over how to regulate the sector, but it finally reached a decision last year that could overhaul the industry and set a new standard for the blue economy. The new regulations cast a wide net.

Let’s dive in.

The Building Blocks of Life (and Commerce)

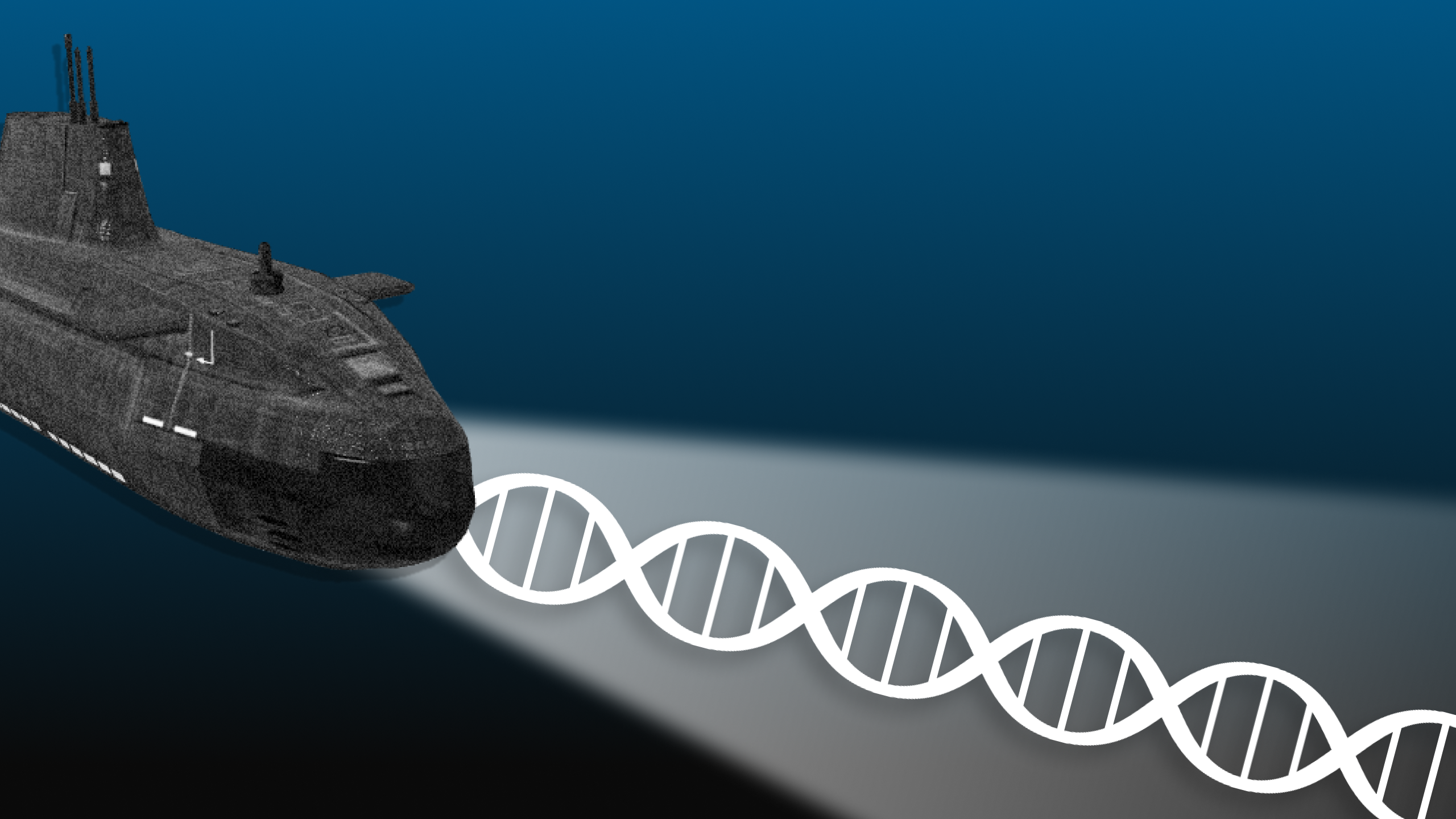

You’re probably wondering how companies sift through trillions of creatures inhabiting Earth’s oceans to find a useful DNA strand. The answer: They let the scientists do it for them. Professor Robert Blasiak, an ocean sustainability scientist at the University of Stockholm, told The Daily Upside that commercial entities don’t take a submarine out into the middle of the ocean with a bucket and a dream. Instead, biodiscovery, also known as “bioprospecting,” is largely done by publicly funded research agencies on the hunt for new species. Scientists then pop those species’ genetic sequences into giant, open-source databases so taxonomists can better understand how the new critters fit into the animal kingdom.

That’s where commercial operations kick in, because anyone can access those public databases. The most famous, GenBank, has been up and running since 1982 and has somewhere in the realm of 3.7 billion genetic sequences on its books, as of 2023. While these databases may have been created for scientific purposes, they’re mouth-wateringly valuable for pharmaceutical firms, chemical companies, biotech startups, and many more. These companies deploy bioinformatics tools that sift through the mountains of DNA data and hunt for proteins that might have some commercial application. If they find something promising, they’ll run tests, and if the results are promising they’ll slap a patent on the genetic code.

Jacques Upfront-Costeau: Blasiak noted it’s a great system for companies because they avoid the nontrivial upfront costs of trekking into the deep sea. “It’s really expensive to get out into these areas […] It’s basically the public through their tax dollars, which ended up at national research agencies, which ended up funding these research cruises. And the commercial part comes two or three steps later,” he said. Blasiak doesn’t begrudge the companies for deploying this tactic, however. “There’s a gut reaction to think: ‘Oh, those sneaky companies.’ But then I think the other side of it is: If this material is out there, and you’re able to develop a new anti-cancer drug or something, why not be using it?”

The patented genetic sequences eventually wind up in a diverse range of products with huge economic potential. Blasiak said his team found five drugs developed from marine genetic resources that added up to $1 billion in sales and licensing revenues every year. However, he said medicine is just one part of the biotechnology puzzle:

- A recent example was industrial enzymes that use genetic resources to make laundry detergent that works as well in cold water as it does in hot. Blasiak said the environmental impact of the world washing its clothes in cold water would be significant.

- Marine genes can also be spliced into land-living organisms. In one case, canola was genetically modified to contain the healthy fatty acids only normally found in fish. “That’s a game-changer because so much of that is linked to human nutrition,” he said.

Sharing is Caring

The patenting of marine genetic resources is a fairly concentrated field, and according to Blasiak, it’s getting more so:

- In 2009, just 10 countries accounted for 90% of marine genetic patents. By 2017, those countries accounted for 98% of patents.

- Blasiak said this is largely due to the computing power needed to run bioinformatics technology and the cost of developing products like pharmaceuticals. “In order to participate in that sector of biotechnology, you need to have deep pockets, a lot of patience, and a high capacity to accept the risk that you’re just going to end up with nothing at the end of it,” he said.

One company, German agro-chemical giant BASF, accounted for 47% of those sequences in 2018, a fact that caused a media stir at the time, which Blasiak characterized as undeserved. “They’re not doing anything illegal,” he said. “There’s nothing that they’re doing wrong. They invest massively in research and development.”

Who Owns the Sea (Except Poseidon): Legitimate arguments do exist around the patenting of marine life, starting with whether ocean life should be patentable in the first place. Dr. Colette Wabnitz, a marine scientist at the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions, told The Daily Upside that “a compelling argument to be made against allowing patents on naturally occurring sequences,” and that patenting certain sequences could “hinder scientific progress by restricting access to the sequences for further research.”

Wabnitz added: “Importantly, it often excludes countries and institutions where the original genetic material was sourced, both in terms of recognition and benefit sharing, further exacerbating limitations on access.”

Sea Change

In 1982, the UN introduced the idea that material found in the high seas (i.e., the large swathes of ocean beyond national jurisdiction) is the “common heritage” of all mankind. That suggests some form of benefits-sharing so even landlocked countries can reap the sea’s rewards.

But it’s been a legal free-for-all. In 2014, the UN began enforcing the Nagoya Protocol treaty, which banned “biopiracy” by making it illegal to take DNA sequences from another country’s waters. But in the international high seas — approximately 47% of the Earth’s surface — anything’s up for grabs.

Or at least, that was the case. Last year, nearly 80 countries signed the United Nations Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction Treaty, also known as The High Seas Treaty. It’s the result of 15 years of international wrangling and, according to Blasiak, “a really big and really important step.”

Once the treaty comes into force (UN policymaking and ratification being fairly glacial), researchers will have to use a tracing system that Blasiak compared to a QR Code for their research trips. “That tracks everything that they collect during that same period, which will feed into a system that enables traceability of those genetic sequences,” Blasiak said. Then, if anyone wants to patent those sequences or commercialize them in any way, there will be a benefit-sharing obligation. That means they’re no longer free for companies.

But Blasiak doesn’t anticipate this will dissuade companies, given that the territorial-waters Nagoya Protocol works much the same way. “If you are a Swiss pharmaceutical company, and you found some really neat genetic material in Papua New Guinea and you want to use it, then you have to enter into an agreement with the government of Papua New Guinea to use it,” he said, adding that most benefit-sharing agreements involve maybe 1%-2% of profits.

The treaty is a huge shift in terms of how we view the economic potential of the oceans. On the one hand, some countries advocated for the high seas to remain a place where commercial enterprises can enjoy heightened freedoms, while others argued for the common heritage of mankind meaning that mechanisms would be needed to share the sea’s rewards. With the High Seas Treaty, the needle has shifted more towards the “common heritage” side of the spectrum. UN treaties though… they’re more guidelines than actual rules, right?