Going Off Script: Can Hollywood Survive a Writers Strike in the Streaming Age?

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

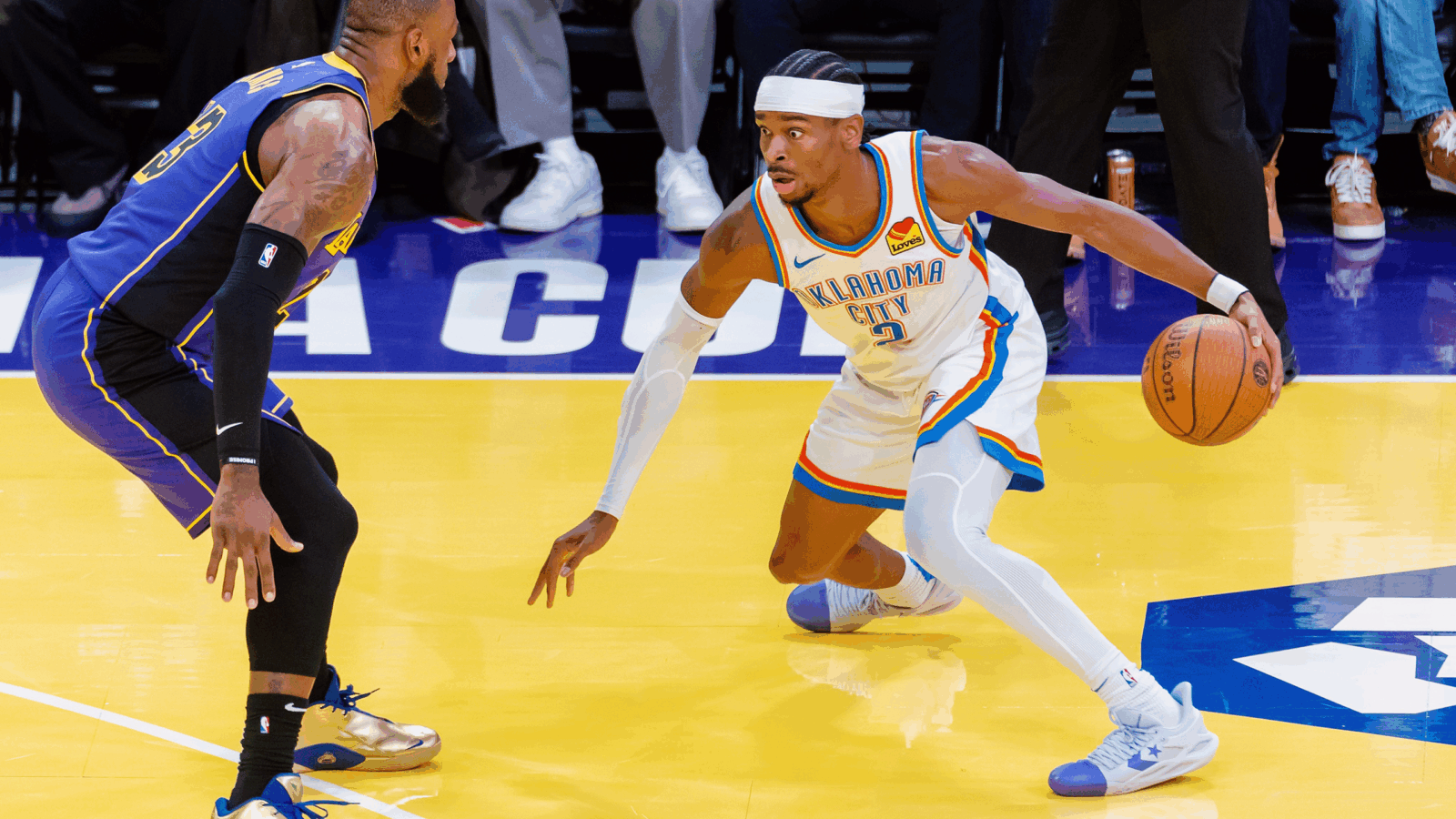

On January 2, 2008, Conan O’Brien, then host of NBC’s 12:30 a.m. Late Night program, sat behind his desk with, uncharacteristically, little to say. He bantered with the audience, riffed with the studio band, danced a bit, and, eventually, spun his wedding ring on his desk like a coin, asking the live crowd to count the seconds before it toppled over.

In TV parlance, he was vamping. No prepared monologue, no bits, no sketches. Nothing was written. Why? Two months prior, the Writers Guild of America engaged in a strike, one that lasted 100 days and by some estimates cost the entertainment industry over $2 billion.

The major sticking point for the WGA at the time: the emergence of so-called “New Media,” now simply known as “content distributed on the internet.” Essentially, writers wanted to be fairly paid when their work was primarily distributed or later showed up on the internet and made everyone else more money.

The strike worked. The guild successfully negotiated for WGA standards to apply to made-for-internet content, with budgets analogous to TV, and walked away feeling victorious… or so it seemed.

Perhaps understandably, the 2008 pact was built on a fundamental misunderstanding of what has become the dominant distribution mode today: streaming. Now, the Writers Guild is gearing up for a widely-expected strike this Spring with the goal of revising the terms to account for the Brave New World of NetflixHuluDisneyMax+.

And that’s what we’re looking at today: why the guild is insisting on a rewrite of the pact, why it comes at a precarious time for streamers, what a production shutdown could mean, and why there may be some middle ground between the guild and the studios.

So find your old DVD of On the Waterfront, but keep the volume down and let’s dive in.

Everything is Copy

In some regards, it’s never been a better time to be a writer in Hollywood. Work is more plentiful than ever as streamers and major studios, desperate to sate their churning-and-burning audience’s demand for new content, have turned television production into a veritable content firehose. COVID-related blip aside, the number of scripted English-language television shows has increased every year for well over a decade, delivering countless opportunities to the writers in showbiz:

- Last year, 599 scripted TV shows made it to air, according to the accounting of FX Networks chairman John Landgraf, who has made charting the road to a possible “Peak TV” an annual tradition at January’s Television Critics Association event.

- In 2021, 559 shows hit the airwaves versus a measly 210 shows aired in 2009 (remember cable? Remember broadcast TV?).

Despite the fact that there were less than half as many shows 14 years ago, even rank-and-file Hollywood writers could maintain a comfortable middle-class lifestyle. That’s no longer the case and earlier this month, the WGA made their gripes explicit. On March 7, members voted overwhelmingly (over 98% of 5,643 casted votes) to approve a “pattern of demands” ahead of once-every-three-year negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) this May.

Labor Relations Rerun: Writers’ strikes aren’t exactly an anomaly in Hollywood. Before ‘23 it was ‘08. Before ‘08 it was ‘88. Before ‘88 it was ‘81, and ‘73, and ‘60. In fact, this year’s strike nearly occurred in 2020, the last time negotiations were held and before COVID cooled everyone’s meddle for a fight.

Each time it comes down to the same thing: residuals, or the compensation Hollywood talent receives when their work is reused, re-aired, rereleased, or redistributed. You might know them as “reruns.”

Think back to the good old days of television. Studios favored a model of 22-episode seasons, with the intent that the show would run as long as possible. The industry standard set a threshold for 100 episodes upon which a show would enter syndication — and everyone made out relatively well. It’s why the talent, including writers, behind Friends or Seinfeld have steady sources of passive income as their shows continue to play on TBS, Comedy Central, WGN, Nick at Nite, and other cable and broadcast networks.

Today, we live in the era of 8-episode limited series or comfort-show-as-background-noise, and instead of Nielsen ratings, streamers have accurate data from cloud servers somewhere showing just how much, exactly, a show has been streamed or re-streamed. But residuals don’t quite work the way they used to, and writers see the fight to modernize residuals as this year’s marquee battle.

I’m Building a Team: Another major sticking point for writers: calling for the end of so-called mini-rooms. Writers are irked by the modern practice of studios hiring a small group of writers to break the story of a short-episode order season before handing off the work to more experienced showrunners to crack the actual episode scripts. Writers say it’s reduced the amount of work available and has stunted career momentum.

They also say they’re far more likely to work at guild-standard minimum rates:

- Roughly half of all writers work at the minimum in 2021-22, compared to just 33% in 2013-14, and 98% of entry-level staff at minimums, compared to 86% in 2013-14, according to the WGA.

- Meanwhile, in the world of feature script writing, the WGA says writers are also losing out: “The current minimum for a first draft non-original screenplay is just $60,932, which is only 1.2% of the minimum budget threshold of $5 million—or 0.3% of a still-modest $20 million budget.” And in a world where the box office has been sacrificed at the altar of streaming, you can all but kiss backend points goodbye.

“Writers in aggregate are undercompensated in this business relative to the financial value of their contributions,” Franklin Leonard, film executive and founder of the screenwriting organization The Black List, told The Daily Upside via email. “And I hope the outcome of the negotiations acknowledges that historical fact so that the business collectively can see better financial outcomes in the future.”

Downstream Effects

So where would a strike land studios and streamers? Shows on a daily churn, like O’Brien’s in 2008, would again be left in a lurch. But when it comes to scripted narrative shows, any prolonged production shutdown wouldn’t be felt for at least a few months. Analyzing which major platform would be affected the most provides an interesting case study in corporate priorities and strategies.

Studios and their streamers are already undergoing the brutal whiplash of spending big to launch a full-fledged streaming service and quickly realizing it is not nearly as sustainable a business model as when, say, NBCUniversal made bank on a broadcast network, cable subscription fees from affiliated channels, and the occasional box office hit from their affiliated movie studios. Comcast president Mike Cavanagh said during the company’s fourth-quarter earnings call in January the company expects to spend $3 billion bolstering its streaming service Peacock this year. Last year, Peacock generated revenue of $660 million.

A writer’s strike, needless to say, throws a wrench in some plans:

- On the one hand, it would leave platforms like Peacock prone to possible multi-month stretches with no new content to offer eager-to-unsubscribe customers. On the other hand, it could help balance budget sheets to shareholders’ likings.

- “The [platforms] who don’t have that much content will be the most impacted, though their viewers are not that attuned to a schedule and may not notice a slowdown,” Michael Pachter, entertainment industry analyst at Wedbush Securities, told The Daily Upside. “And the huge advantage are the services like HBO that remain committed to weekly episode distribution, leaving some time and wiggle room for production gaps, as opposed to the platforms like Netflix that dump all their episodes at once.”

Studios like HBO have had another advantage in recent years.

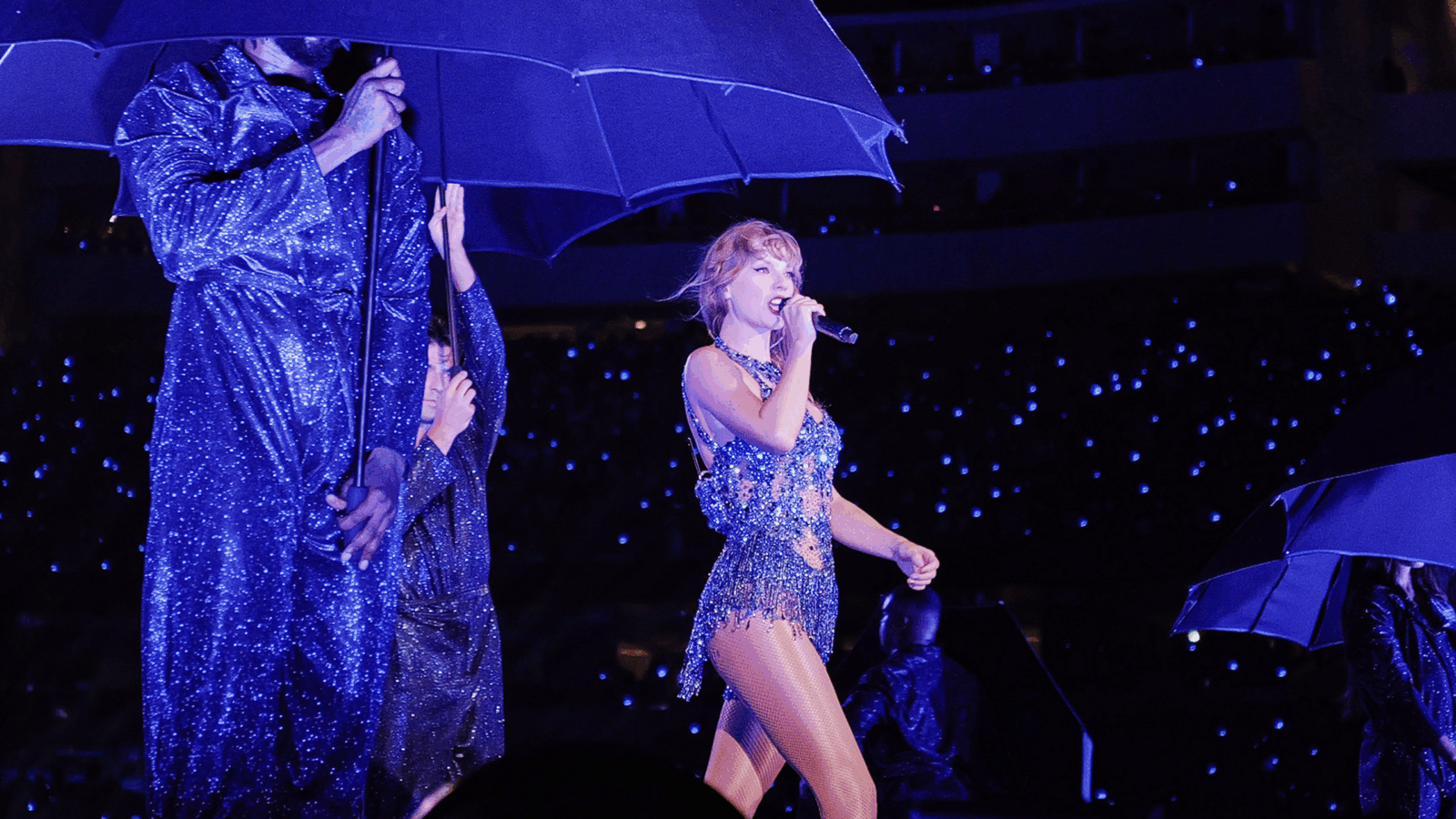

It Came From Outside the USA: The entertainment industry has gone global. Streamers plow into every market they can, and viewers the world over — even us notoriously insular Americans — are more likely now than ever to watch an international show with either subtitles or dubbed dialogue. In fact, one major sticking point in writers’ demands is that the current residual formula is based on domestic subscribers only.

Netflix, in particular, has prioritized international content it either directly produces or licensed from international production houses, like Squid Game from South Korea, Germany’s Dark, or Japan’s Midnight Diner: Tokyo Stories.

“Netflix has very few shows that a lot of the audience watches. Five percent will watch anime, 5% horror shows, 5% reality cooking shows. There are small pockets for every genre. And they’ve done so much production overseas. They can backfill a delayed season of Stranger Things with a foreign show they have licensed or produced,” Pachter added.

So Who Will Win?

No side ever comes out completely victorious in an above-the-line Hollywood strike, though the guild is likely to win a fair amount of concessions. Compared to the value of the work they create, Hollywood’s writing expenses remain relatively cheap. And with studios and streamers already rethinking their new business models, there may be plenty of wiggle room to meet demands — i.e., content production is at an all-time high, and studios may consider the tradeoff of increasing costs if it means decreasing the number of productions by the same amount.

“One thing about NBCUniversal is that we have vast libraries, we have The Office, we have Brooklyn Nine-Nine,” Susan Rovner, NBCUniversal’s chairman of TV and streaming, recently said during a panel at SXSW. “When you look at a lot of the streamers and how they program now it’s three seasons, eight episodes each season and we’re done.’ So they’re not building those libraries, and I think that’s a mistake.”

Meanwhile, Disney’s Bob Iger recently mused about finding a way to retap the revenue streams from physical home media distribution — DVD sales were profitable, Disney+ subscriptions not so much.

In other words, both the writers and the studios feel squeezed by the current landscape, meaning maybe, possibly, there’s a middle ground somewhere where both sides are happy.