Saudi Arabia Pulls Back as Trump Reemerges on World Stage

Saudi Arabia’s Mammoth Public Investment Fund Turns Inward Just As One of the Country’s Top Allies Reclaims the White House.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

As the whole world watched vote tallies roll in during the US presidential election earlier this month, Rory McIlroy’s thoughts turned to golf.

One of the world’s most famous pro golfers, McIlroy wasn’t just musing about a simple round of 18 holes with President-elect Donald Trump. He was alluding to a high stakes bet by one of the world’s biggest, and most politically fraught, investors: the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF).

Trump’s business ties to Saudi Arabia — and close relationship with the Kingdom during his first term in office — made McIlroy wonder whether the president-elect could help buoy a long-awaited, stalled merger agreement between the PGA Tour and its Saudi-backed rival LIV Golf, which disrupted the sport by handing out lavish contracts to lure away talent, all bankrolled by PIF cash.

“He might be able to do something if we get [Elon] Musk involved too,” McIlroy, who has declined to join LIV events, quipped to Sky Sports.

But for all the excitement about – and potential benefits of – having a close business ally of the Gulf state about to retake the White House, Saudi Arabia’s PIF is actually in the process of turning inward. A PGA-LIV merger could happen, but it would be a throwback to the past decade of pizzazz more than a reflection of a more conservative future.

Last month, the PIF’s governor, Yasir Al Rumayyan, told a conference in Riyadh that Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, which holds $925 billion in assets, will cut its share of overseas investments to as low as 18%, down from the current 21% and a 30% record in 2020.

Already this year, the PIF has pared down and sold off major stakes. Investors have begun to realize that doing more business with the PIF will require doing more business in Saudi Arabia, with the days of the fund throwing around easy cash abroad coming to a close.

And, in a major shakeup, the CEO of one of PIF’s biggest domestic investments, the fantastically expensive futuristic planned city NEOM, stepped down on Tuesday in what could signal a more frugal realignment at home.

The Prince and the Paper

Set up in 1971 by a royal decree to invest funds (aka lucrative oil revenues) on behalf of the government, the previously mundane holding company emerged in the last decade as a global investment giant with an eye for splashy deals on international markets. That was largely at the behest of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who was anointed chair in 2015.

Bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler and a “massive gamer,” immediately steered the PIF to invest $45 billion into SoftBank’s $100 billion venture capital Vision Fund in 2016, making it one of the world’s biggest tech investors.

The returns, however, were underwhelming, though a tech rally led to a full-year gain in 2023 after a loss-making 2022.

There was also $20 billion put towards Blackstone’s infrastructure fund, part of a relationship that deepened earlier this year when the asset manager announced it would launch a Riyadh-based multi-asset class investment platform with an initial $5 billion seed from the PIF.

Arguably the most high-profile investments in the PIF portfolio are sports assets — in 2021, the fund acquired an 80% stake in English Premier League football club Newcastle United for £305 million ($387 million). That was increased to 85% earlier this year in a deal that valued the club at a much loftier £1 billion ($1.3 billion). Its quest to disrupt — or unseat — the PGA reportedly cost $2 billion in outlays. Billions more have been spent on boxing and domestic soccer, among other sports.

Newcastle languished in eighth place going into this weekend, despite spending hundreds of millions on transfer fees to acquire new players. Leaked WhatsApp messages with one former minority owner in the club suggest the purchase was made at the urging of bin Salman.

But now the PIF is in pullback mode.

Buyers Turned Sellers

An analysis of SEC filings earlier this year revealed the PIF dumped stakes worth hundreds of millions in Amazon, Microsoft, and Salesforce, replacing them with call options on fewer shares. It sold off $600 million in BlackRock stock, a nearly $1 billion stake in cruise ship operator Carnival, and a $750 million stake in travel company Booking Holdings.

Meanwhile, a Japanese regulatory filing revealed earlier this week that the fund reduced its stake in Japanese video game giant Nintendo to 6.3% from 8.58%. That divestment, in particular, was a notable symbolic move, suggesting bin Salman has accepted a more shrewd investment strategy that blunts the influence of his personal interests like video games and sports.

Under the crown prince’s influence, the country has spent billions to try and solidify a reputation as an esports and gaming hub, including by hosting the first Esports World Cup in July.

Overall, Securities and Exchange Commission filings show the value of the PIF’s portfolio of publicly-traded securities in the US fell from $38.9 billion at the end of the second quarter last year to $20.6 billion at the end of the second quarter this year.

A Crude Explanation

An inward turn, on its face, isn’t unreasonable. A country — or a sovereign wealth fund — ought to invest at home. The PIF’s pivot inward is certainly directed to buttress domestic economic growth, but that’s also because the last two years have brought a need for a buttress.

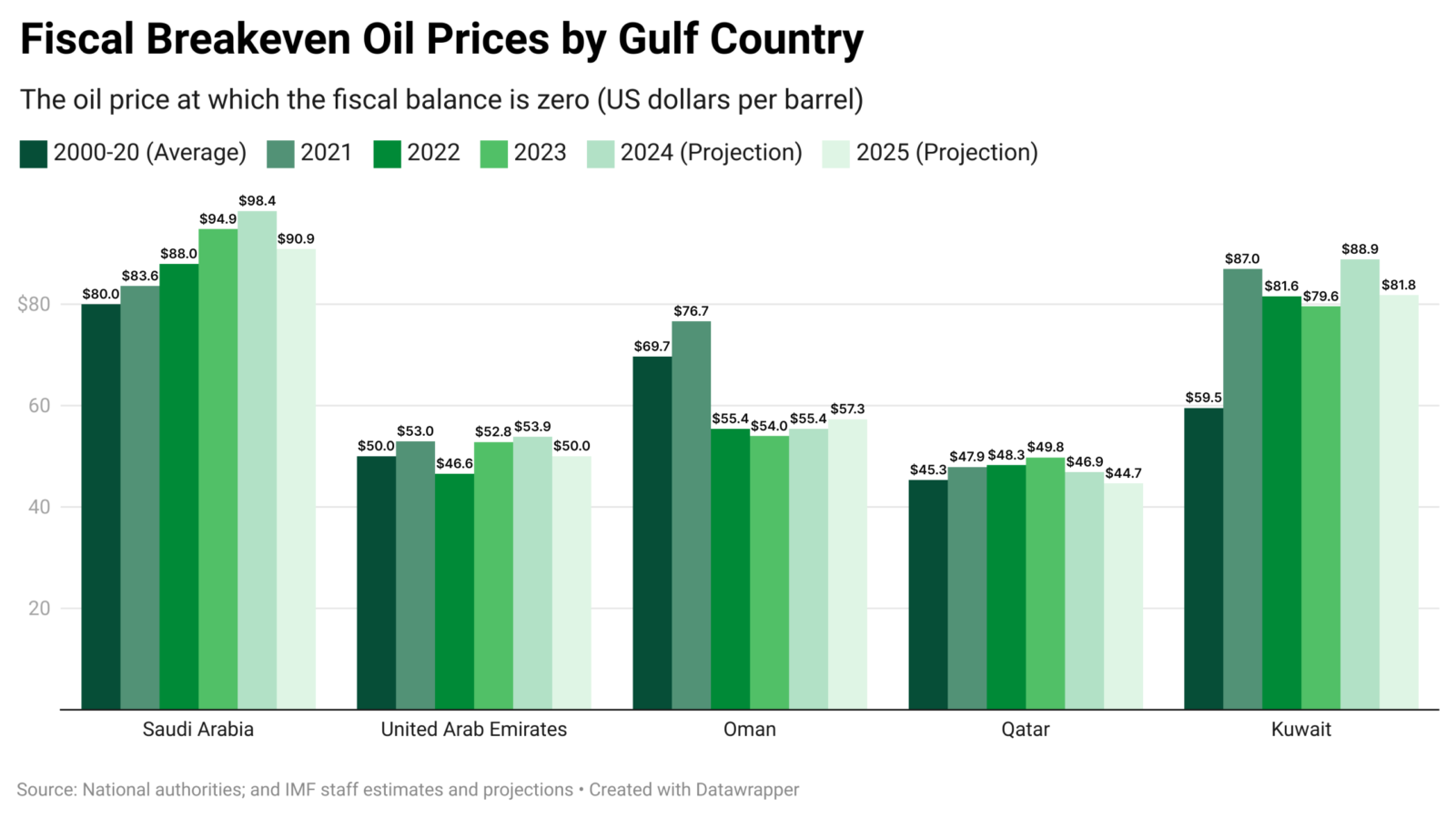

Roughly 40% of Saudi GDP and 75% of the country’s revenues come from the petroleum sector, according to IMF estimates. In the past two years, that GDP has been hammered by output cuts adopted by OPEC+, the organization of oil-producing countries that includes Saudi Arabia, in a bid to stabilize global oil prices.

The government’s budget has flipped between deficit and surplus over the years and, earlier this month, Saudi Arabia reported deficit spending for the eighth straight quarter.

For the first nine months of the year, the shortfall amounted to 58 billion riyal ($15.5 billion), while the finance ministry said last month that it expects an annual deficit of 118 billion riyal ($31.4 billion) this year. That figure is equal to 3% of GDP and a nearly 50% increase from budget projections made late last year, not to mention a significant increase from the 81 billion riyal ($21 billion) deficit in 2023.

The downturn has led the PIF to start shedding even some of its homegrown stakes for cash. Last week, the fund announced that it hired Goldman Sachs and Saudi National Bank to sell a $1 billion, 2% stake in Saudi Telecom, the kingdom’s primary landline and mobile phone operator.

Giga Reality Bites

PIF’s divestments and inward turn come amid pressure to keep pace with a goal to invest $1 trillion dollars in non-oil sectors by 2030 to fuel economic diversification.

A cornerstone of that plan is a series of so-called giga-projects, ambitious mega infrastructure gambles: Neom, the $500 billion planned urban development on the Red Sea is the most famous of the lot.

But Saudi Arabia’s budget downturn has meant scaling back some of the projects, most of which are at least partly bankrolled by the PIF. For instance, The Line, a futuristic city that was initially planned to house 1.5 million residents by 2030 is now set to host just a fraction of that: 300,000, according to an April report by Bloomberg.

Last week, Neom’s longtime CEO, Nadhmi al-Nasr, left. No official reason was given.

Despite the cutbacks, the giga-projects have helped further Saudi Arabia’s goal of drawing in global investments, partly through the network of connections built by the PIF’s global spending spree.

For example, Diriyah, one of the giga-projects, has locked in roughly $1 billion of deals with European firms and is in talks for more, according to its CEO.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s foreign direct investment inflows amounted to 96 billion riyals ($25.6 billion) in 2023, besting government targets. That was an increase of 50% over 2022 numbers when factoring out a one-off Saudi Aramco pipeline deal.

Trump Card: And while the PIF and Saudi Arabia may be adopting a more insular worldview, they are counting the days until Trump returns to the most powerful office in the world, given his and his family’s longstanding ties to the Gulf Region.

Trump’s first foreign visit in his previous term was to Riyadh in 2017.

The Trump Organization and Saudi real estate developer Dar Global announced in July that they are collaborating on a Trump-branded tower in Dubai. London-listed Dar Global also said that month that it was working with the Trump Organization on a Trump Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, runs a private equity firm that Saudi Arabia has invested roughly $2 billion in, according to Congressional records. It reportedly made millions in fees, but so far hasn’t turned a profit for its clients.

Trump’s family is nevertheless expected to chase more deals that could align with Saudi interests.

“We will definitely be doing other projects in this region,” Eric Trump, the Trump org’s executive vice president and the president-elect’s son, told the Financial Times before the Jeddah announcement. “This region has explosive growth, and that’s not stopping anytime soon.”