Chinese Government Puts a New Leash on its Financial Sector

Beijing plans to establish a Central Financial Commission, which will act as a watchdog for the country’s $61 trillion financial sector.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

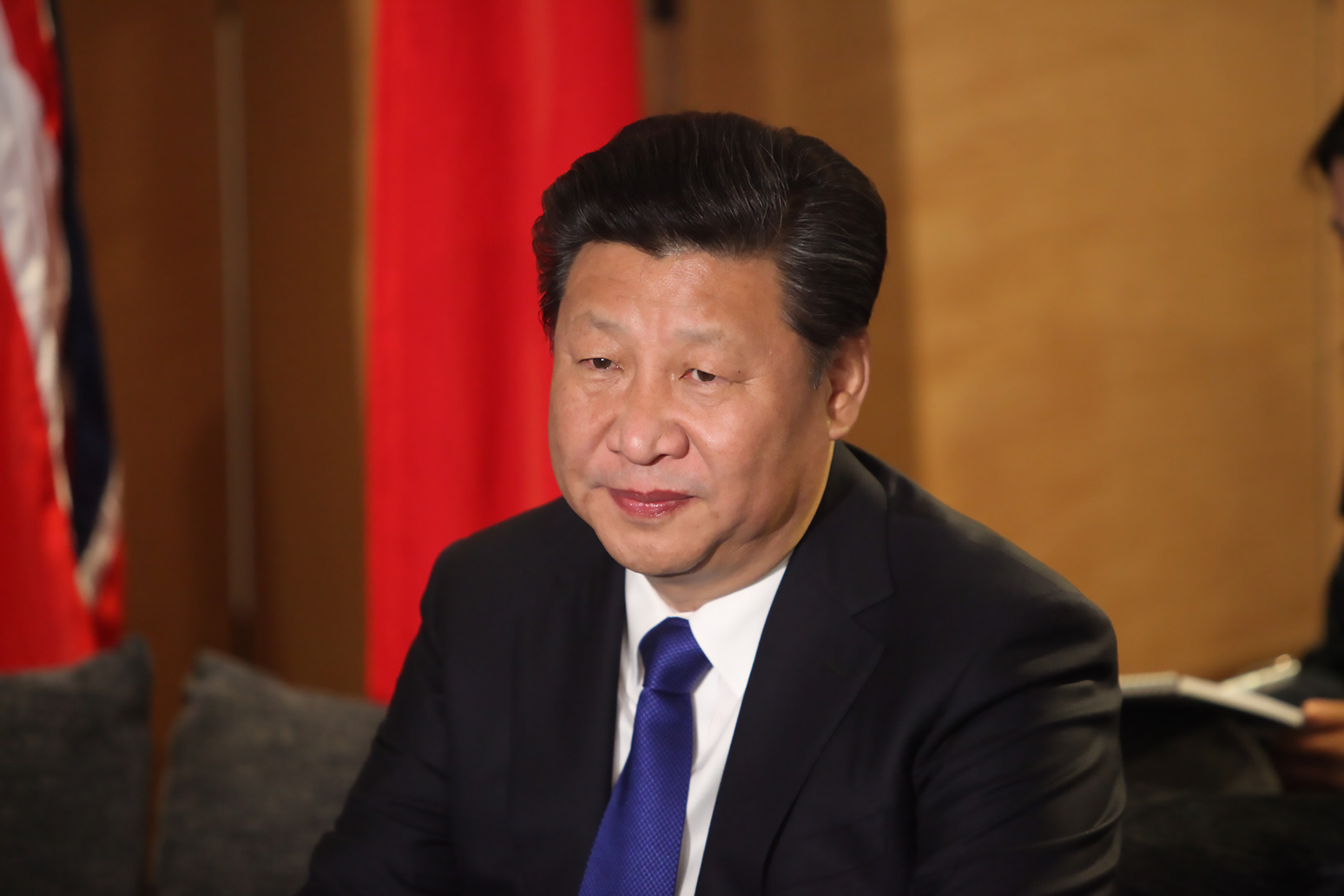

“To get rich is glorious,” Deng Xiaoping proclaimed as China embarked on its path to hypercapitalism a generation ago. Under President Xi Jinping, it’s less glorious than dangerous.

Beijing plans to establish a Central Financial Commission, which will act as a watchdog, decision-maker, and regulator for the country’s $61 trillion financial sector, the Financial Times reported. Keep in mind: China already has a state securities regulatory commission.

Never Bounced Back

China didn’t experience the pandemic rebound seen by other developed nations. Today, unemployment among young workers is growing, exports are in a slump, and investor confidence is dwindling. Plus, the country’s tech sector is facing heavy sanctions from the US and EU.

But China’s biggest financial woes lie in the real estate industry, a formerly booming sector and job creator that has fallen into disarray in the past two years after Beijing placed borrowing limits on real estate firms. New home prices are falling, a glut of apartments sit vacant, and major developers such as Evergrande and Country Garden — formerly gold standards for property managers — face hundreds of billions of dollars in debt.

Now, Xi feels it’s time for the Communist Party (CCP) to make things right:

- The Central Financial Commission intends to address China’s economic troubles by placing Xi and the CCP as the de facto leaders of the country’s financial sector, while weakening established government groups such as the People’s Bank of China and the China Securities Regulatory Commission.

- With the extended control, the CCP could deleverage the real estate sector, shore up the finances of indebted local governments, and clamp down on speculation and corruption, the FT reported. It would also place Xi and the party at the head of major business deals such as mergers and joint ventures.

“The line between the party and the government has become decisively blurred, so there is no way that the new financial watchdogs will contradict with what the party wants,” Yan Wang of global investment firm Alpine Macro, told Reuters in March when the commission was first announced.

Safe and secure: In recent months, Xi and the CCP have become obsessed with national security and party control while the economy has taken a back seat. Authorities have raided the offices of foreign businesses, and state broadcasters have accused Western countries of trying to steal sensitive information from important Chinese businesses. A new national watchdog is essentially the latest move to de-westernize China’s economy and extend the CCP’s influence.