What Happens If Section 230 Gets Sunsetted?

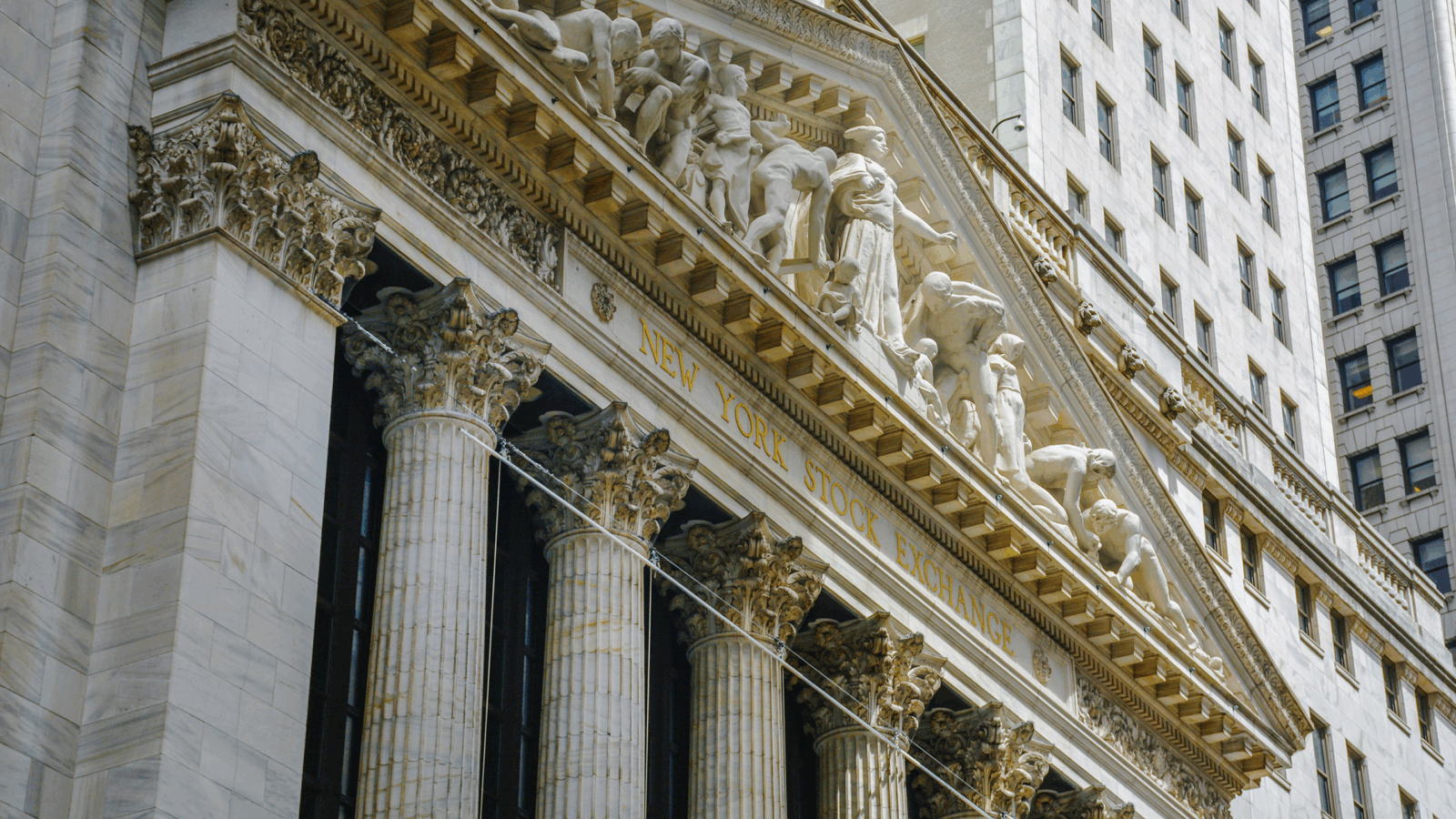

A new bipartisan bill just introduced in Congress aims to make tech companies responsible for content posted on their platforms.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

We were given a lot of things in 1996: the advent of Hotmail, the Spice Girls’ timeless classic “Wannabe,” the cinematic triumph that is “Space Jam” … the list is endless.

It also gave us a small piece of legislation that would shape the internet as we know and love it (well, love to hate it) today. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act became law that year, and it set the stage for some of the biggest fights between Big Tech companies and governments, angry parents, and various other belligerents they’ve encountered. Now, a bipartisan bill has been introduced in Congress to sunset Section 230 — so what is it, how does it work, and what happens if it’s dismantled?

What is Section 230?

Section 230 contains a section occasionally called “the 26 words that created the internet.” Here they are in all their glory:

“No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

That line means platforms can’t be held legally responsible for illegal content published by a third party. So if someone uploads some horrendously illegal video to YouTube, for example, YouTube isn’t liable for that video.

Section 230 also establishes that platforms can remove material they deem to be: “obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected.” That means that Meta, Twitter, or whoever sets the rules about what you can say or post on their services.

What’s So Bad About That?

Lawmakers have chafed against Section 230 because it gives Big Tech a lot of free rein compared to traditional publishers. The law was written long before social media had become an all-encompassing juggernaut. Some lawmakers also argue that the law provides platforms too much cover to avoid responsibility for what users can or can’t post — back in 1996, the internet didn’t constitute such a giant slice of human conversation.

Both Joe Biden and Donald Trump bandied about the idea of scrapping or altering it during the last election cycle. But last Sunday, two members of the House Energy and Commerce Committee (one Republican, one Democrat) put forward draft legislation for sunsetting Section 230. The representatives said that although Section 230 was fit for an era where Tom Hanks could win the heart of Meg Ryan over email (“You’ve Got a Tinder DM” just hasn’t got the same ring to it) its usefulness has soured.

“Tech companies are exploiting the law to shield them from any responsibility or accountability as their platforms inflict immense harm on Americans, especially children,” the committee said in a statement. The draft legislation would nullify Section 230 on December 31, 2025, giving lawmakers (and Big Tech lobbyists) 18 months to forge something new to take its place. “Our bill gives Big Tech a choice: Work with Congress to ensure the internet is a safe, healthy place for good, or lose Section 230 protections entirely,” the committee said.

A lot of what happens next depends on what Washington cooks up to fill the Section 230 vacuum, but losing those protections could be pretty catastrophic for tech companies. Without them, regulators might be able to pry into companies’ inner workings vis à vis how they police the content that continually flows onto their platforms. Worse still, they could be left vulnerable to lawsuits not just from regulators, but class-actions as well. Given the unthinkable volume of stuff being uploaded every hour of every day, that’s a lot of legal exposure.

The bill would still need to work its way through Washington, and there’s plenty of time for Big Tech to chip in its own two cents, but it’s still a troubling development for all the Zuckerbergs, and Musks out there.