Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

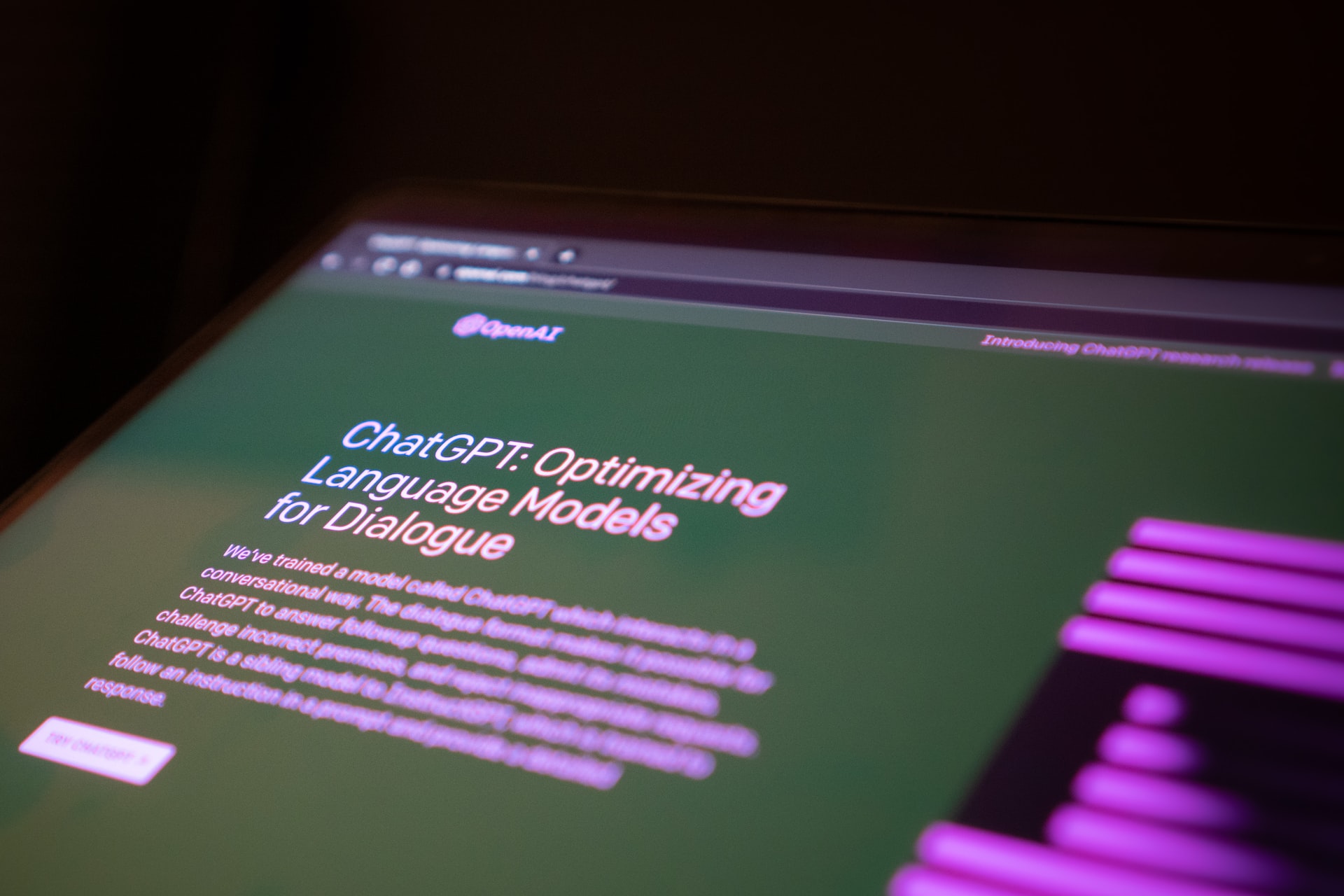

Unless you’ve been living off the grid somewhere in the Azores, you’ve probably heard of a little thing called ChatGPT.

It’s a very impressive chatbot that was created by a company called OpenAI and released to the public in November that uses generative AI. By ingesting huge amounts of text written by actual humans, ChatGPT can create a large range of texts, from song lyrics to résumés to college essays.

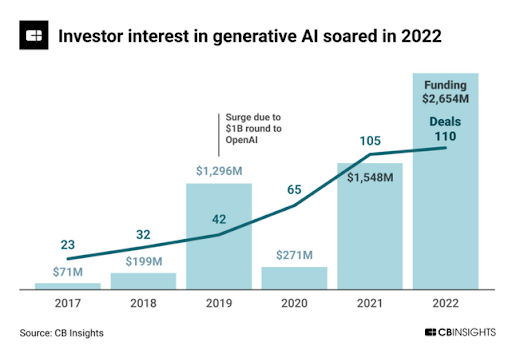

ChatGPT kicked off a maelstrom of excitement and not just among users, but also Big Tech companies and investors who poured money into any company that had the phrase “AI” anywhere on its pitch deck. But generative AI tools capable of whisking up text, images, and audio have also prompted widespread hand-wringing about mass plagiarism and the obliteration of creative industries. (At the Daily Upside, “better than bots” is our new rallying cry.)

For today’s feature we’re going to see whether AI truly lives up to the hype, and what legal guardrails are there to steer its progress. So sit back, relax, and if at any point you hear a voice saying “I’m afraid I can’t do that, Dave” please remain calm.

Commercialization Stations

When generative AI tools were just being used to create silly memes, i.e. yesterday, the debate about robots and our future seemed mostly theoretical. Once it became obvious that this was a deeply commercializable tool was when things started to get tricky.

ChatGPT upped the ante because it kicked off an arms race between Microsoft and Google. Microsoft announced in January it would invest $10 billion in OpenAI, and a few weeks later it announced a new version of its search engine Bing which, instead of showing users a page of search results, would give written answers to questions using ChatGPT’s tech.

The news sent Alphabet, which hasn’t ever faced serious competition in search, like, ever, scrambling before announcing it would create its own generative AI search tool, called Bard. Unfortunately, on Bard’s debut, it made an error in one of its answers and investors responded by wiping $120 billion off Google’s market value in a matter of hours.

Google’s knee-jerk response was short-sighted but understandable. ChatGPT’s overnight popularity sparked an ongoing onslaught of articles suggesting that generative AI is the biggest thing to happen to the internet since social media, and specifically that it would forever change the way we search – and the verb we use when we do so. So sure, Google noticed.

As it turns out, Google needn’t have rushed. The new generative-AI-powered Bing turned out to be just as fallible as Bard, but also seemingly borderline sociopathic. In one example, it insisted that the year was still 2022. In another, it went totally off the rails and told a New York Times journalist to leave his wife.

News websites that deployed generative text tools have also learned the hard way that mistakes happen, particularly when it comes to math. CNET published 77 stories using a generative AI text tool and found errors in half of them.

So what’s the point of a search engine you have to fact-check, and is all the hype even remotely justified?

Dr. Sandra Wachter, an expert in AI and regulation at the Oxford Internet Institute, told The Daily Upside generative AI’s research abilities have been greatly overestimated.

“The big hope is that it will cut research time in half or is a tool for finding useful information quicker… It’s not able to do that now, I’m not even sure it’s going to be able to do that at some point,” she said.

She added ChatGPT’s self-assured tone amplifies the problem. It’s a know-it-all that doesn’t know what it doesn’t know.

“The issue is the algorithm doesn’t know what it is doing, but it is super convinced that it knows what it’s doing,” she said. “I wish I had that kind of confidence when I’m talking about stuff I actually know something about… If your standards aren’t that high, I think it’s a nice tool to play around with, but you shouldn’t trust it.”

What Is Art? Answer: Copyrightable

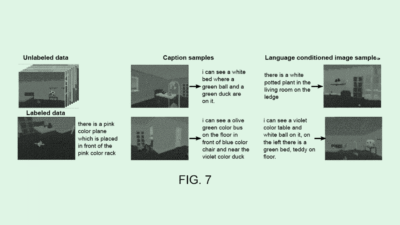

While ChatGPT sent an existential shiver down the spine of journalists and copywriters, artists had already confronted the problems of accessible, commercializable AI in the form of image generators such as Stable Diffusion and Dall-E. Like ChatGPT, these tools work by scraping hoards of images — many of which are copyrighted.

Legal lines are already being drawn in the sand around AI-generated images. Getty filed a lawsuit against Stability AI (the company behind Stable Diffusion) in February for using its pictures without permission.

Similar legal battles could play out between search engine owners and publishers. Big Tech and journalism already have a fairly toxic codependent relationship, with news companies feeling held hostage to the back-end algorithm tweaks that change how readers access news online. Now generative AI search engines could scrape text from news sites and repackage it for users, meaning less traffic for those sites — ergo less advertising or subscription dollars.

The question of generative AI copyright is two-pronged, as it concerns both input and output:

- It’s possible that to get the input data they want, AI companies will be forced to obtain licenses. In the EU there are exemptions to copyright laws that permit data scraping, but only for research purposes. “The question of is this research or is this not, that will be a fighting point,” Wachter said.

- Once the AI tool has spat out a chunk of text or an image, who owns the rights to that? In February last year the US Copyright Office ruled an AI can’t copyright a work of art it made, but who can copyright it remains an open question.

Data protection law will also apply to generative AI makers, but Wachter stressed there is no new legal framework tailored for the technology. The US published its blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights last year, but that was in October, a month before ChatGPT made its dazzling debut. The EU also has an upcoming AI Act, but again, it just didn’t see generative AI coming to the fore so fast.

“The new regulation will do next to nothing to govern this,” Wachter said. One section of the existing guidelines that could potentially adapt to generative AI tools is a set of new standards of transparency and accountability for chatbots. The idea is to make it clear to consumers when they’re talking to a cheery customer service bot, rather than a world-weary customer service employee.

But even if companies were forced to watermark AI works, Wachter doesn’t have confidence that’d be useful. “That’s a cat-and-mouse game, because at some point there will be a technology that helps you remove that watermark,” she said.

So What Can We Do?

Good or bad, better or worse, generative AI is here now and it’s not going away. Wachter thinks there is a three-pronged approach needed to make sure ChatGPT and its brethren don’t become garrulous bulls in the internet’s china shop:

- Education: although schools have blocked access to ChatGPT to head off students from getting it to write their homework for them (as have major banks including JP Morgan and Citibank) Wachter thinks kids and grownups alike need to play around with AI tools so they can become familiar with their strengths and limitations.

- Transparency: despite the potential of future AI watermark removals, a little digital badge from the developer saying “an AI made this” could be a useful step towards people treating its output with a more critical eye.

- Accountability: the spam and misinformation potential of ChatGPT-style tools is enormous, so Wachter envisions a future where platforms have to tightly control the spread of AI-generated content.

Regulation never moves as fast as technology, but the furor around generative AIs may prompt lawmakers to plant their flag.

“The main thing that I really want to stop hearing is just the panic around it [AI],” Wachter told The Daily Upside, adding: “It’s a fun technology that can be used for many purposes, and yet we only focus on the horrendous stuff that will bring doomsday.”

She said short of plagiarizing artists’ work, the tech could legitimately be used in interesting ways in the art world, which has always managed to incorporate new technologies as tools.

“If Monet had had a laptop back then he would have used it,” she said. “We’re betting he would have been a fan of Photoshop’s blur tool.

Disclaimer: this article was written by a human journalist possessed of free will (arguably), fallibility (allegedly), and self-awareness (usually).