Small Town America is Paying for New Residents

Communities are hoping that a handful of incentives might be just enough to tip the scales and create a new generation of residents.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

People used to joke that they wouldn’t live in places like Paducah, Kentucky, if they paid you to. Now they actually do. In an age of skyrocketing home prices, remote work, and a collective sense of isolation, small towns like Paducah are hoping that a handful of incentives might be just enough to tip the scales and create a new generation of residents.

Make ‘Em An Offer They Can’t Refuse

Communities throughout the country — mostly in areas like the Midwest or the South — have been ramping up their efforts to attract new residents and build or maintain their tax bases. One of the most popular strategies falls under the broad umbrella of “relocation incentives”:

- This includes everything from plots of land and cash (sometimes as high as $15,000), to memberships at co-working spaces, and free gear at recreation and wilderness centers.

- In some places, the incentives are on-brand small-town charm. In addition to stipends, land, and a gym membership, Lincoln County, Kansas, offers “a dozen farm-fresh eggs every month for a year.”

But in effect, they’re tools to “reverse the brain drain,” said Evan Hock, COO of MakeMyMove, an online marketplace connecting communities with prospective residents. “Brain drain” refers to educated people — often with a bachelor’s degree or higher — leaving a particular area, resulting in a loss of capital and properly trained workers. Rural states lacking in major cities like New Hampshire, West Virginia, and Vermont tend to be affected the most, The Washington Post reported.

“Rather than recruit Amazon to relocate, a city like Greensburg, Indiana, can recruit individual Amazon workers who bring themselves, families, jobs, and income,” Hock told The Daily Upside. “It’s an economic development play. They’re going to invest some dollars and incentives to make that move, and the return is the long-term economic impact of that worker.”

Pass the Remote: One of the biggest shake-ups to come out of the pandemic was the rise of remote work. It may not be as ubiquitous as it was during lockdowns, but in October 2023, roughly a quarter of US households still had someone working remotely at least one day a week, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse survey. These fully remote workers are targets of opportunity for towns and small cities like Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Rochester, New York.

“Remote workers are highly attractive because they can bring themselves and their jobs with them,” Hock said. “The majority of the programs on our site are targeting remote workers, but others are starting to grow, and you’ll see programs that address specific workforce shortages like teachers, nurses, and police officers.”

Hock added that the remote workers taking advantage of relocation incentives tend to have college degrees and are making upward of $100,000 a year.

Sooners and Hoosiers

Tulsa, Oklahoma, has set the gold standard for relocation incentives. Since the Tulsa Remote Program first attracted incoming remote workers in 2018, more than 50,000 people have applied for the incentives, and about 3,000 have been accepted.

The program’s success inspired other locales to get in on the action.

Abby Elpers, marketing director for the Evansville (Ind.) Regional Economic Partnership, said her city began offering relocation incentives last spring in addition to what the state already provides. In the program’s first nine months, it helped attract multiple new residents that have “generated around $1.2 million in economic impact, both in direct and indirect spending,” she told The Daily Upside. “Also, oftentimes, they’re bringing their spouses and family members, who are joining our workforce as well.”

And, surprising to some of these town officials, there hasn’t really been a pattern as to where people are moving from, either. “We thought we would have a better chance going after people previously tied to the region; maybe they grew up here or went to school here,” Elpers said. “But they’re actually coming from all over — California, Washington, Wyoming, Texas, Florida, Illinois, New York, Atlanta.”

The Price of Living

However, the wide range of where relocators are coming from — and why relocation incentives are particularly attractive right now — can be partially explained by the state of the housing market, which is… well, not very good.

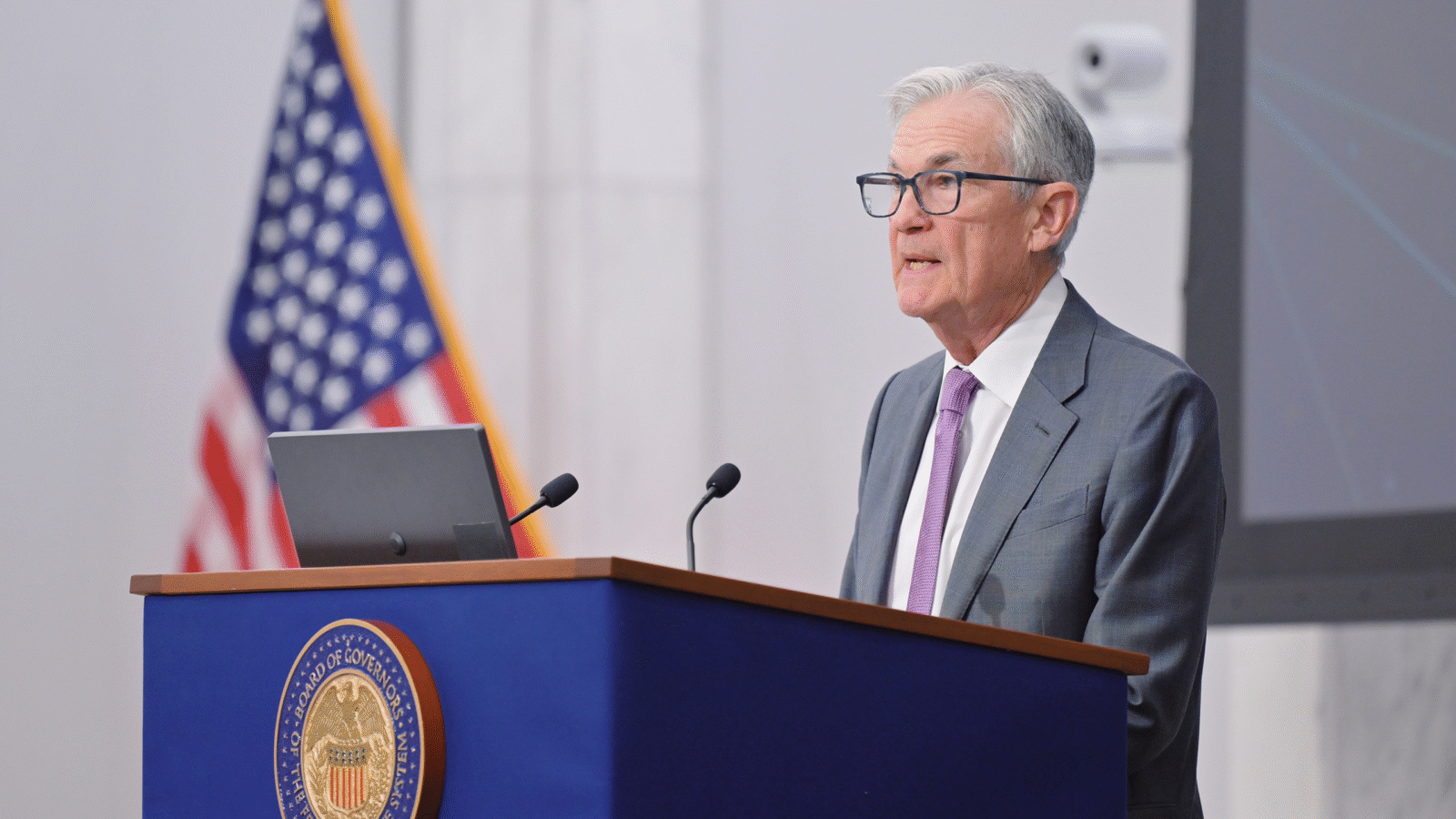

To combat inflation and hopefully gently cool the economy down, the Federal Reserve first raised interest rates in March 2022. Then they did it again, and again, and again, until rates were increased a total of 11 times, and they now sit between 5.25% and 5.5%. All of this made money more expensive to borrow, which also meant mortgage rates would follow:

- In January 2022, the rate of the average 30-year mortgage — the most common type of home loan — was 3.2%, according to Freddie Mac. By November 2023, the rate had spiked to 7.8%. Rates have since fallen by a full percentage point, but there’s still another problem.

- The country doesn’t have enough inventory, with a deficit of about 3.2 million homes, global real estate development firm Hines told Axios. And the ones that are around aren’t selling: The National Association of Realtors reported that existing-home sales in 2023 slid 19% year-over-year to roughly 4.1 million, the lowest level in almost three decades.

It’s gotten to the point where many living in major cities or coastal regions feel hopeless about ever achieving the dream of that green lawn with a white picket fence — or for the more metropolitan type, that garden apartment next to an independent coffee shop. Even California, the nation’s most populous state and one that had continued to grow ever since it gained statehood in 1850, began losing residents in 2021. The Public Policy Institute of California cited the state’s high cost of living as one of the main drivers for emigration.

One of Evansville’s newer residents is Logan Jenkins, who runs a non-profit focused on entrepreneurship. He had previously lived in Wyoming, Denver, and Southern California, and he feels owning a home is the most obtainable now.

“For me, I can see that home ownership in the near future is definitely possible here,” he said.

I’m So Lonely: Beyond the affordability and free perks, smaller cities also can provide people with a certain sense of belonging. Despite existing in a population of 335 million, roughly 17% of American adults report a regular sense of loneliness, according to a 2023 Gallup survey. It’s not as bad as it was during the pandemic, obviously. But still, 44 million lonely people is not good, and many mental health experts have classified it as an epidemic:

- Those feelings of isolation can be even harsher in major cities; 79% of adults aged 18 to 24, who often reside in urban areas, reported feeling lonely regularly, according to global health company the Cigna Group.

“Oftentimes, yes, people are looking for a lower cost of living,” Elpers said. “But in a lot of cases, they were drawn to Evansville because it looked like a small town where they feel like they can be part of a community compared to where they were.”

Are the Incentives Enough?

Most relocation incentive programs are relatively new, so their impact on population and local economies is still in its infancy. Many people in New York City and Los Angeles aren’t in a big rush to move off the coasts just yet. And even in Tulsa’s case — where the incentive program is partially funded by the non-profit of billionaire oil tycoon George Kaiser — it was already a large city with a population comparable to Minneapolis or New Orleans.

But there are examples of steady growth. Harmony, Minnesota, started offering incentives in 2014; cash rebates that go toward the purchase of a handful of homes a year. Vice President of Community and Economic Development Associates Chris Giesen told Governing that’s enough to meet the city’s goals. In 2020, Harmony actually saw a 3% growth in population.

On the other hand, there’s also the potential for these types of programs to neglect current residents. Cornell University’s Cristobal Young told The Atlantic that incentive programs are “bad policy that just takes money from settled residents and gives it to people who are more mobile.” Even if the incentives are privately funded, that can pressure surrounding communities to start their own.

But with the median rent in a place like San Diego sitting at around $3,000 a month, a two-bedroom in Muskegon County, Michigan, for one-third the price can sound pretty appealing. Plus, you get two free beach parking passes.