How the Great Wealth Transfer is playing out for Billionaires

The oldest among us are richer than ever, so are the richest. So what happens when the oldest and richest start passing their wealth along?

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

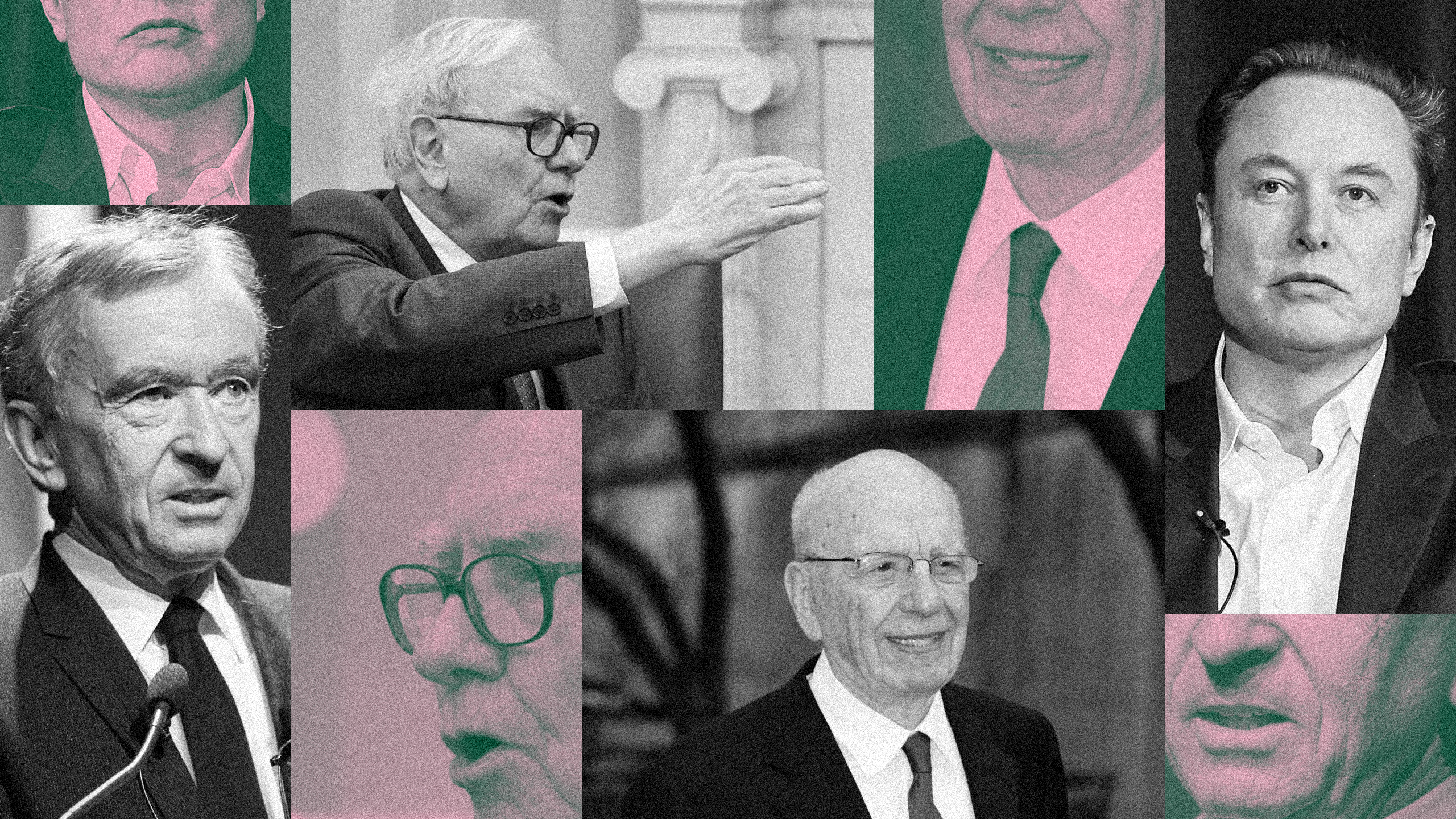

Two narratives have dominated the news cycle about the current state of wealth distribution. Firstly, that baby boomers hold a historically large proportion of wealth that will soon start to make its way down to the young’uns (by which we mean the middle-aged Generation X and prematurely middle-aged millennials). Secondly, that the richest 1% of society has never been richer. A recent report claimed Elon Musk, the wealthiest person on the planet and as of this week, the first person to bag a net worth of $400 billion, is the richest man to have ever lived. There’s plenty to unpack there, but what we ostensibly have is an economy that is top-heavy in two ways: The oldest among us and the richest among us have more than ever.

Our focus today is on that very top slice of the 1%, the billionaire class, whose ranks are growing. At the top of this year, there were more billionaires than ever before: 2,781 in total, according to Forbes. That was 26 more than in 2021. The net worth of this year’s billionaires also set a record — of $14.2 trillion, up $2 trillion from 2023. In that very top rung of the wealthy, there are plenty of older folks, and there are signs that the current class of billionaires is starting to pass their riches along. Last year, one study found the median age of your average billionaire was 67, but research from Forbes in April found that every billionaire under the age of 30 inherited their wealth rather than making it.

So what does it mean for the wider economy that billionaires’ children are inheriting the world? “For economists, the question might be reduced to: What is the role of inherited wealth in all wealth,” Neil Cummins, a professor of economic history at the London School of Economics, told The Daily Upside. Cummins added that the exact role of inherited wealth in the wider economy is a point of “severe contention.”

Money Fight

One obvious way that the billionaire wealth transfer differs from the rest of the economy is that billionaires can hand over the reins to enormous companies with vast economic and cultural influence.

This week, we saw just how scrappy The Great Wealth Transfer can get among billionaires and their progeny. Media mogul Rupert Murdoch, 93, lost a court case against a clutch of his children after he tried to transfer control of the family trust solely to his son Lachlan, who shares his political bent. Murdoch’s other children — Elisabeth, Prudence, and James — successfully blocked the transfer of power to Lachlan, although Murdoch’s lawyers said they will appeal the ruling. According to court documents, the children’s concerns about what will happen to Murdoch’s media empire after he dies were directly prompted by an episode of Succession. Life imitating art is one thing, but this is more like life copying art’s homework.

Rupert Murdoch isn’t the only billionaire patriarch trying to get his house in order:

- Bernard Arnault, 75, CEO of luxury brand conglomerate LVMH and the world’s fifth-richest person per the Bloomberg Billionaire Index, has strategically placed all five of his children in executive roles within the company.

- In June last year, George Soros, 94, passed control of his philanthropic organization to his son Alexander. Although Soros is currently only hovering around number 480 on Bloomberg’s Billionaire Index, with a net worth of $6 billion, his foundation was reportedly worth $25 billion when he put his son at the wheel.

The Oracle Speaks: There’s one billionaire who is vocally opposed to passing down long-lasting family wealth. The Oracle of Omaha, Warren Buffett, age 94 and the 10th-richest person on Bloomberg’s Billionaire Index, said in a letter published last month that he dislikes the idea of “dynastic” wealth as he transferred a little over $1 billion to his children’s philanthropic ventures. “I’ve never wished to create a dynasty or pursue any plan that extended beyond the children,” Buffett said. “I know the three well and trust them completely. Future generations are another matter. Who can foresee the priorities, intelligence, and fidelity of successive generations to deal with the distribution of extraordinary wealth amid what may be a far different philanthropic landscape?”

The Kids Are Alright

While ultra-rich families do tend to be good at hoarding (and hiding) wealth, it’s not necessarily true that the children and grandchildren of billionaires are wealth sinks. “New wealth is being created all of the time, and it can be created by people who inherited a lot of wealth as well,” Cummins said. “Elon Musk is a great example of a man who inherited a significant amount of wealth, but that’s trivial compared to the wealth he generated.”

While Musk came from a wealthy family, he has denied that he benefited from an inheritance from his father Errol Musk, with whom he has an extremely difficult relationship. Musk said in a tweet that Errol invested “10% of a ~$200k angel funding round” into one of his first companies, Zip2, but said the company was already on its feet.

Of course, we don’t know how many failed Elon Musks there are out there, and the data on how often a child with inherited wealth shows a talent for capitalism similar to that of their forebears is scant. For Musk himself, who currently has 11 children at the age of 53, the question of divvying up inheritance could get really tricky.

Return to Form

While the current allocation of wealth in our society might feel like it’s more top-heavy than ever before, in some ways it could be seen as a return to the status quo. According to Cummins, inherited wealth tends to make up a bigger portion of the economy when that economy is growing sluggishly. The period during and after World War II was a historical exception as economies boomed, and countries also imposed incredibly high tax rates — Franklin D. Roosevelt even tried to bring in a 100% income tax rate above an annual threshold of $25,000 (roughly $484,000 in today’s money). He never got it passed, but by 1944, the top rate of income tax was 94%, and it remained high for decades.

There is also the issue of whether the billionaires of 2024 truly are the richest people to have ever lived. Cummins sees some nuance in the numbers: “We are the richest society that ever lived, and our billionaires are the richest people who have ever lived […] but as a share of the economy, they’re actually less of a share of the economy than they would have been in the past,” he said.

As much as Gen X, millennials, and Gen Z envy their baby boomer forebears, those baby boomers are — when viewed through a historical lens — kind of an anomaly. “There’s been a huge democratization and equalization of wealth-holding, through things like people owning their houses, people owning more stuff,” Cummins said, “That was the economic growth over the 20th century […] So the idea that there’s some new world we’re going into is completely overstated. Because proportionally, the rich own less than they did before.”