Ford May Want to Charge EVs with the Grid in Mind

Ford’s latest patent uses its cars to charge its cars.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

Ford wants to make charging its EV fleet more energy-conscious.

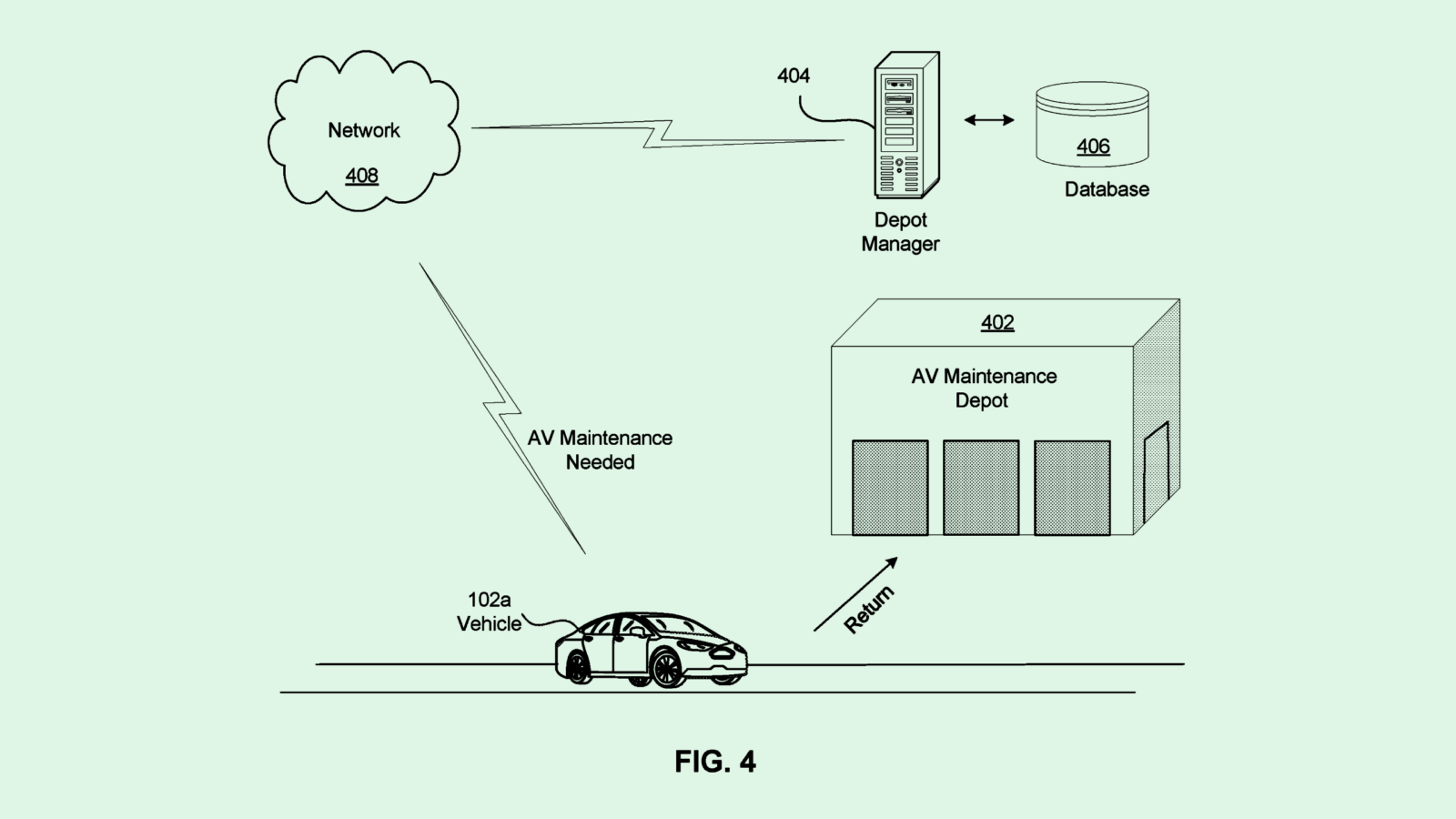

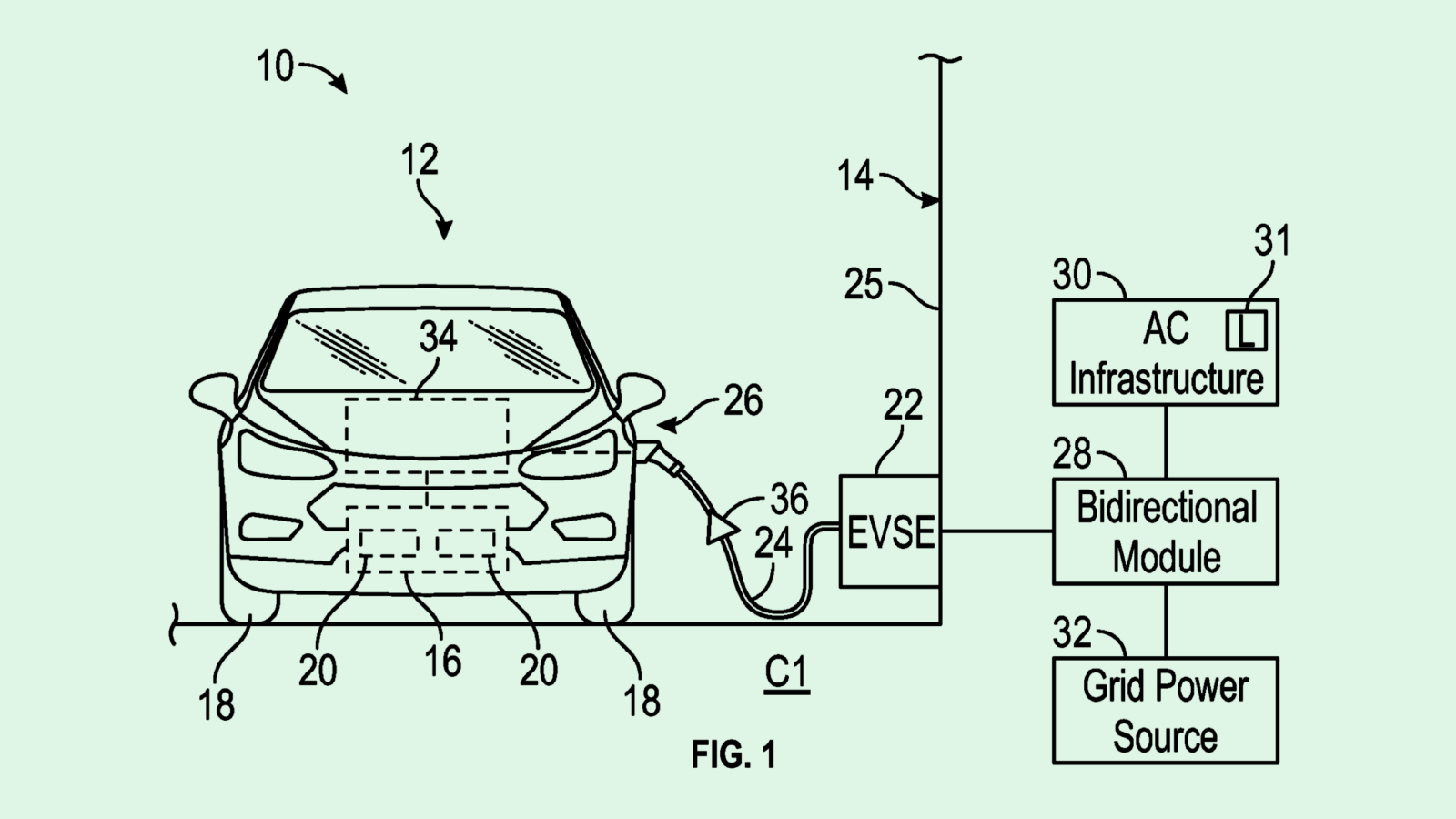

The company wants to patent a system for an EV “charging control system” which takes into account predicted charging demand on the utility grid during certain times to lessen stress and cut down on energy expenses.

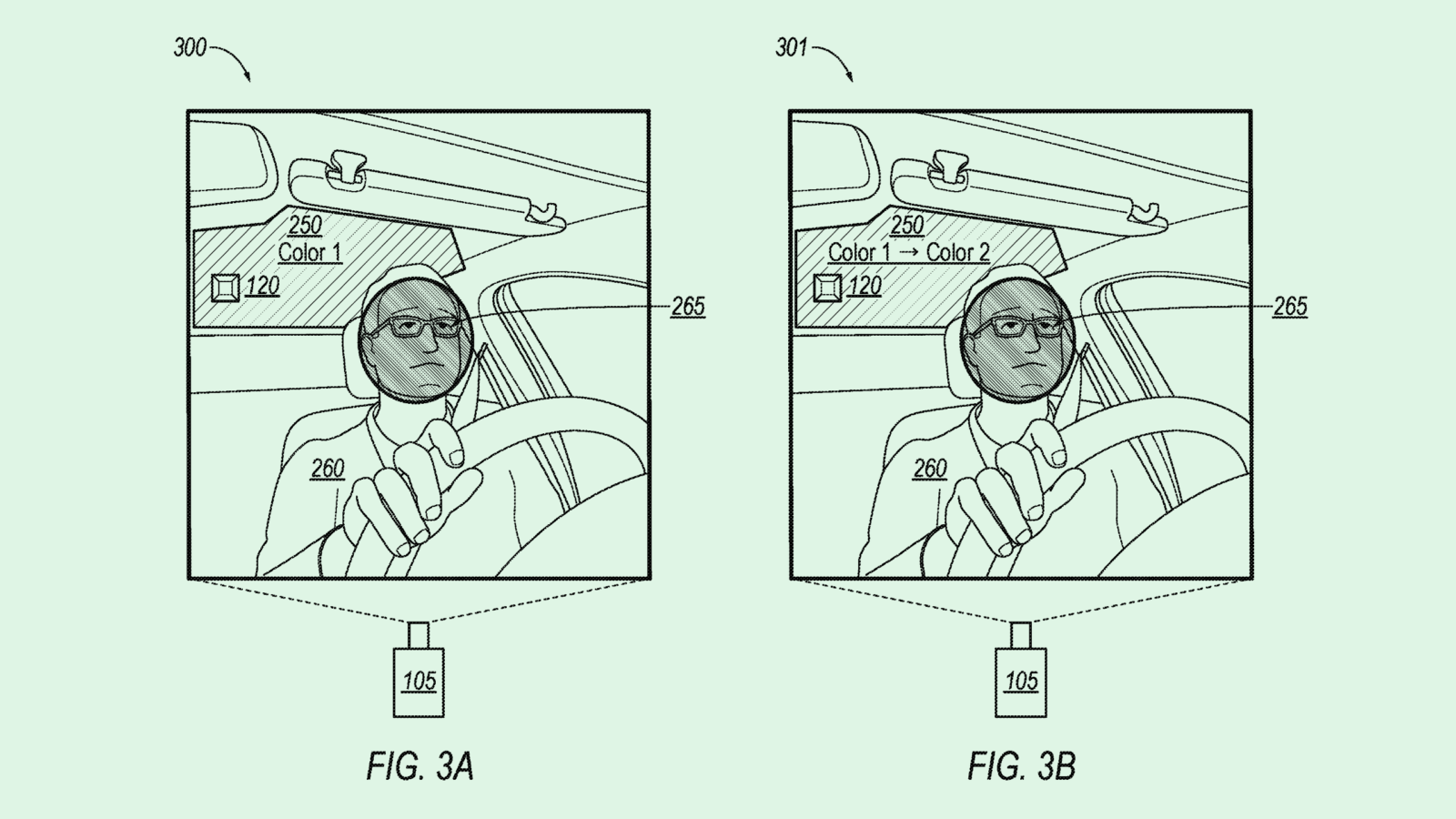

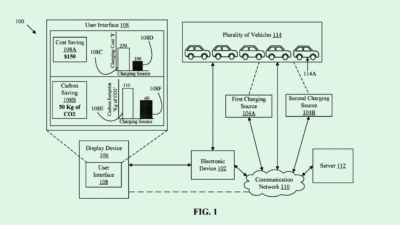

Ford’s system first monitors how much the grid is relying on “reactive power” — the energy that keeps the grid running smoothly, but isn’t doing the heavy lifting — in a given moment. The system monitors a metric called “power factor,” which determines how much of that reactive power the EV is taking up as it charges. The system then only charges the vehicle from the grid if the use of that reactive power is below a certain threshold, and if the power factor metric is within a specific range.

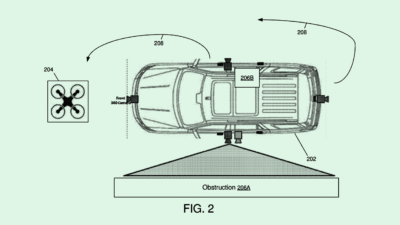

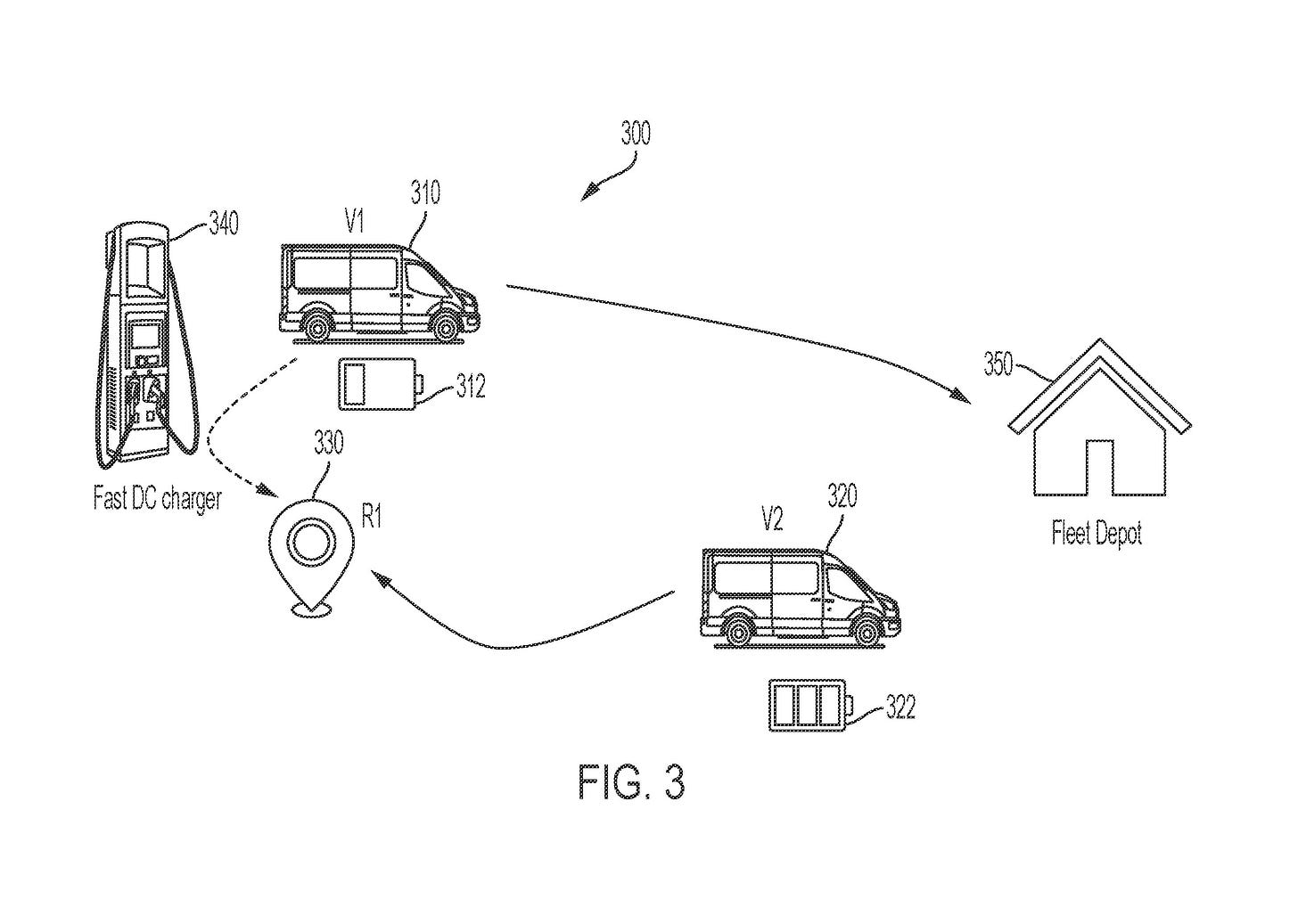

If Ford’s system determines that it shouldn’t charge using the power grid, it will use the vehicles within its fleet to charge each other using bi-directional transfers of power. In layman’s terms, this means that a battery from one car can charge the battery of another car under certain circumstances.

For example, say one car’s battery in a fleet is at 15%, while another car’s battery is at 85%. The car with the higher battery percentage can charge the one with the lower battery percentage so they can both be above a certain threshold.

Ford’s argument for this system is basically that sharing is caring. “ While this depletes a portion of the energy of the first battery, it may be used to increase the charge of a second battery, such that both batteries are above a predetermined threshold,” the company said.

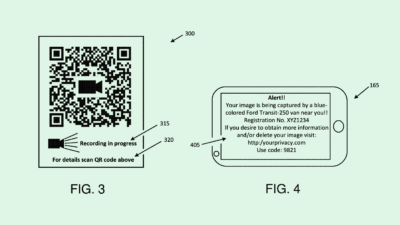

While the impact of reactive power on consumer EV users is relatively low, the same can’t be said for enterprise- or industrial-grade operations. Given that Ford offers a line of EV utility vehicles, adding a method for distribution enterprises to charge them at a lower cost could be a lucrative opportunity, said Matt McCaffree, VP of utility market development at clean energy parking and mobility company FLASH.

Distribution centers specifically are an “interesting challenge to solve for,” said McCaffree. “Those fleets … are typically driving under 200 miles a day, and are really great targets for electric vehicles and electrification.”

Ford’s solution to balancing power between utility vehicles is novel in that no other company or organization has “quite cracked this nut yet,” said McCaffree. However, a lot of companies have been researching how to solve the problem of keeping large fleets of EVs charged in this way, he said, so solutions may be sprawling and “shouldn’t be limited to one patent.”

Though every automotive company has thrown their hat in the EV ring over the years, Ford has been especially ambitious. The company wants to manufacture EVs at a run rate of more than 2 million by the end of 2026 and has filed to patent a number of EV-related inventions. Ford electrifying one of its most popular vehicle models, the F-150, in and of itself shows “how serious they are about this and how big of a player they will be in the future,” said McCaffree.

Getting into industrial and utility EVs with this patent only further proves the case that wide-scale electrification of its lineup is more than just a pet project for the company.