Happy Thursday and welcome to Patent Drop!

Today, a patent from Snap to closely watch its workforce’s emotions could take workplace surveillance a step further. Plus: Intel wants to diversify its deepfake detection algorithms; and IBM wants to keep its AI models from being swayed by bad data.

First, a quick programming note: Monday’s edition of Patent Drop will be an Earth Day special report digging into how Big Tech is both helping and hurting the climate crisis.

Let’s take a look.

Snap’s Workplace Emotion Detection

Snap’s latest patent application may want to keep a smile on employees’ faces.

The social media firm is seeking to patent “emotion recognition for workforce analytics.” Snap’s tech aims to measure “quality metrics” for individuals in the name of “workforce optimization,” with the filing using call-center employees as an example.

“Contact centers typically stress that their employees stay emotionally positive when talking to customers,” Snap noted in the filing. “Employers may want to introduce control processes to monitor the emotional status of their employees on a regular basis to ensure they stay positive and provide high quality service.”

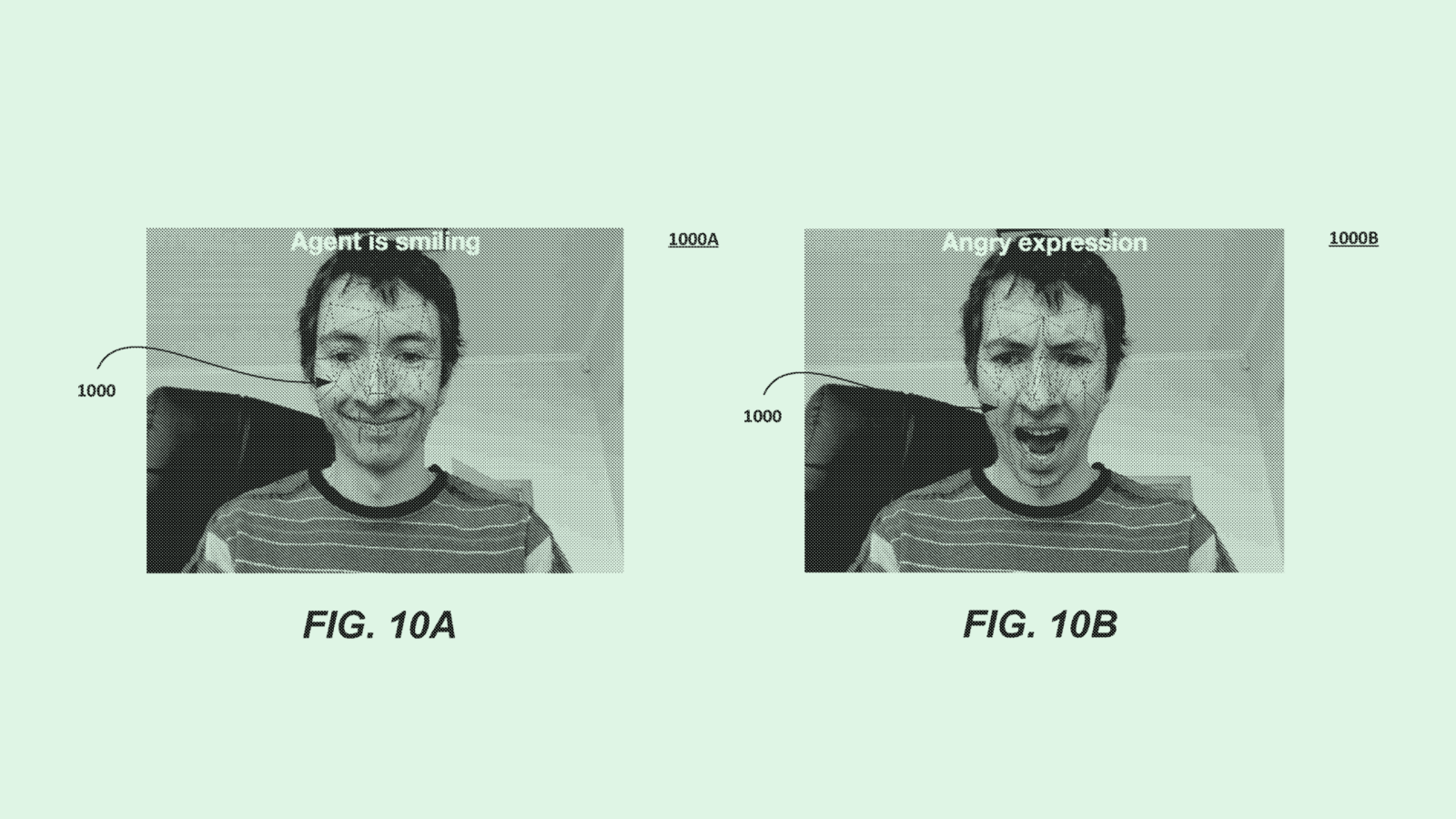

Snap’s system of “video-based workforce analytics” watches the facial expressions of an employee or agent to be “recognized, recorded, and analyzed,” specifically when in a video chat.

Aligning a user’s facial landmarks with what Snap calls a “virtual face mesh,” this system determines whether a user has a facial “deformation” connected with a certain emotion. These facial landmarks may be determined by an AI-based algorithm that compares the user’s facial landmarks to reference images. Basically, if you’re showing anything but a straight face, this system will be able to connect it with an emotion.

For example, a smile may signal a positive attitude, while a furrowed brow may be a sign of a negative one. Audio data may also be collected to determine speech and voice characteristics to inform emotion detection even further.

These emotions may be recorded in an employee record as “work quality parameters,” such as “tiredness, negative attitude to work, stress, anger, disrespect, and so forth,” Snap said. Snap noted that these emotions could be used to inform employer decisions related to “workforce optimization,” such as “laying-off underperforming employees, and promoting those employees that have a positive attitude towards customers.”

Emotion recognition is a common theme in Big Tech patent applications. Amazon has attempted to patent tech for its smart speakers, Microsoft has looked into emotion-detecting chatbots and meeting technology, and Nvidia has filed applications for expression-tracking tech for animation.

Microsoft has even sought to patent tech that similarly aims to track employee emotions — though it looks solely at text data through messages and emails, rather than facial recognition and audio data.

Though Snap is known for its social media and AR offerings, tech firms often file patent applications for inventions outside their wheelhouses. If granted, Snap could gain sole access to a powerful tool for emotional analytics.

However, emotion recognition technology is highly controversial: AI simply isn’t very good at understanding human emotions. Though using multiple forms of data in tandem could help inform an AI model’s output, happiness, sadness, or any other emotion still looks different for everyone.

Different cultures and regions have different forms of emotional expression, as do people who may be neurodivergent. This widespread variety in data makes it nearly impossible for an AI model to capture and understand every form of expression. Instead, systems like this may compare each individual’s emotional expression to whatever the developer deems a point of reference.

“All emotion recognition systems we’ve seen have had biases,” Calli Schroeder, senior counsel and global privacy counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, said in an email.

Even if Snap’s system works perfectly, this kind of surveillance may not be favorable to the employees subjected to it. As workplace surveillance has become commonplace, the practice may be impacting workers’ mental health. A study from the American Psychological Association found that 56% of workers who experienced employee monitoring felt tense and stressed in their workplace. Adding emotion monitoring into the mix could worsen a workplace’s culture and erode trust further.

“There is no reason to have this technology besides increasing workplace surveillance and micromanaging,” Schroeder said.

Intel’s Deepfake Diversifier

Intel wants its AI models to identify all manner of deepfakes.

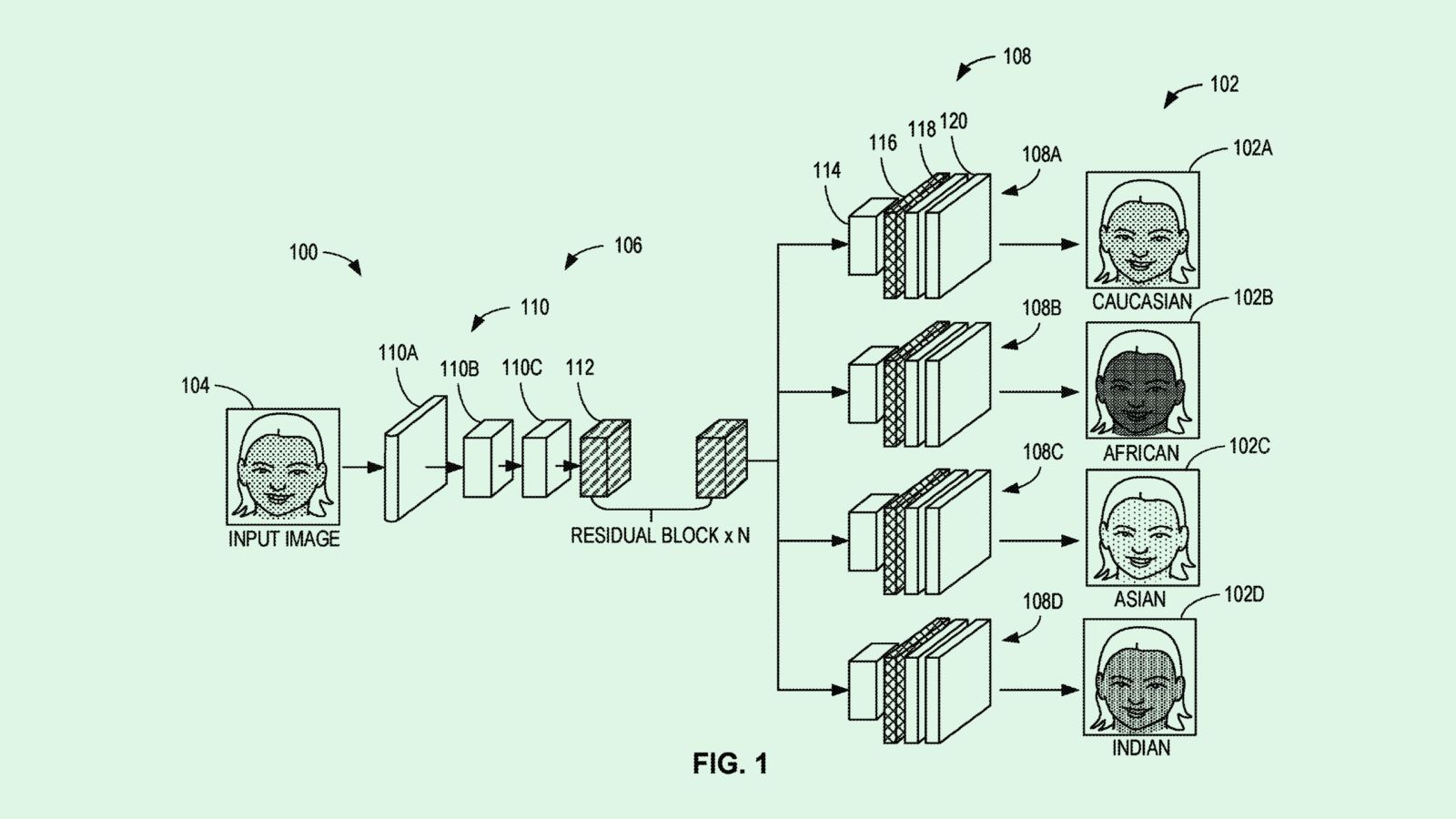

The company filed a patent application for systems to “augment training data” based on diverse sets of synthetic images. This tech uses generative AI to create deepfakes representative of “diverse racial attributes,” aiming to train its models to better detect a wider range of AI-generated imagery.

“Some training datasets include a disproportionate and/or insufficient number of images for one or more racial and/or ethnic domains,” Intel said in the filing. “The resulting deepfake detection algorithm may be biased and/or inaccurate when trained based on the training dataset.”

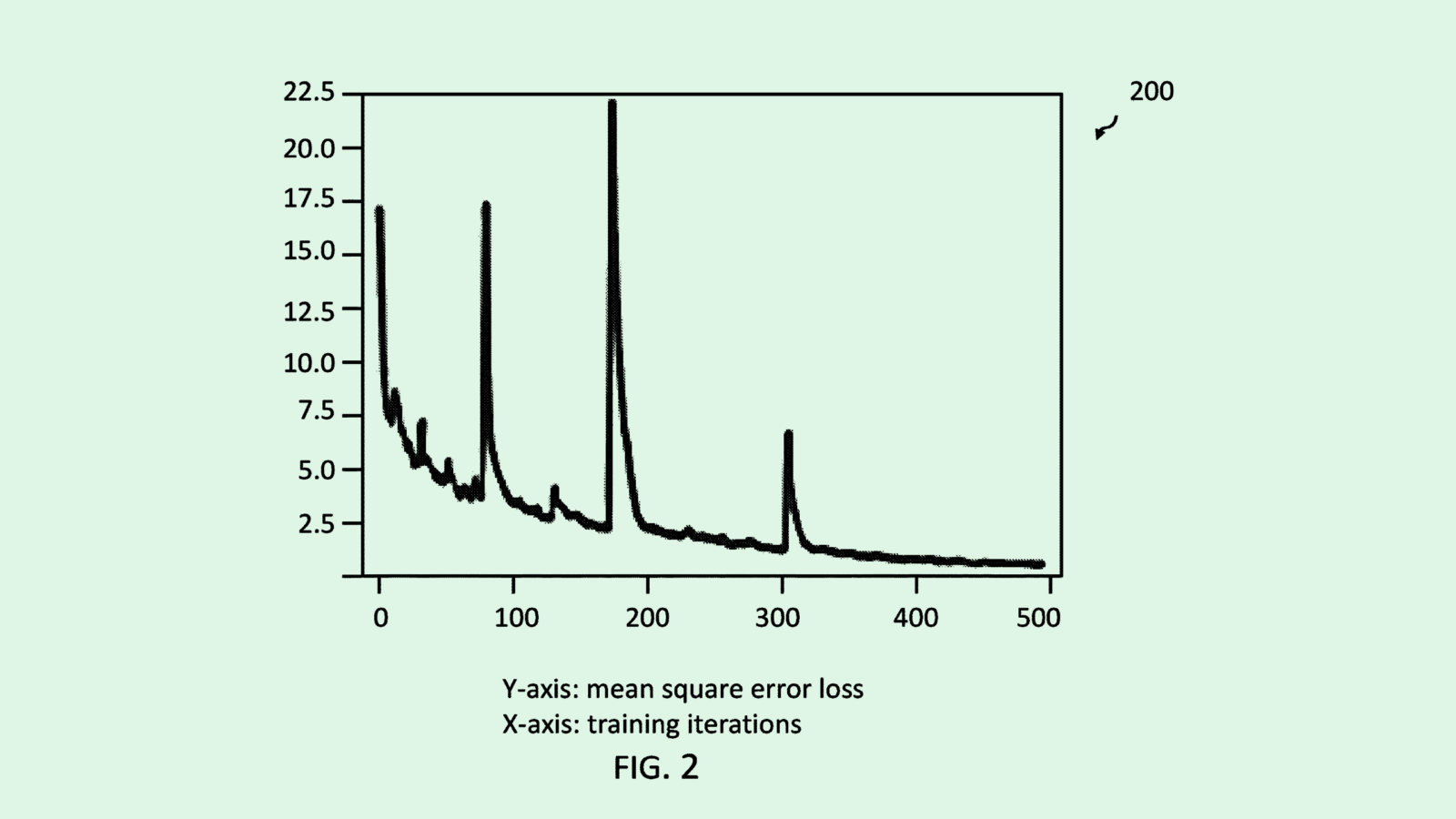

Intel’s tech relies on a generative AI model to transfer “race-specific” features from a reference image to an input image, creating a synthetic image that’s a hybrid of the two (though Intel doesn’t note specifically which facial features this tech may augment). After it’s created, the model employs what Intel calls a “discriminator network” which labels the race of the subject in the image and whether or not the image is synthetic.

Those synthetic images are fed back into the initial training dataset, aiming to create a more robust deepfake detection algorithm. “Augmenting the training dataset with the synthetic image(s) … may reduce bias and/or improve accuracy of the deepfake detection algorithm,” Intel notes in the filing.

With the widespread proliferation of generative AI, plenty of firms have sought patents to take on the deepfake problem. Sony sought to patent a way to use blockchain to trace where synthetic images came from, Google filed an application for voice liveness detection, and a Microsoft patent laid out plans for a forgery detector.

“The technology is becoming so widespread now that it’s hard to know what the future is going to look like,” said Brian P. Green, director of technology ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. “It’s definitely going to be an arms race between generation and detection of them.”

But Intel’s patent highlights an important issue with image-based deepfake detection tech: To have a model that works for all faces, you need a diverse dataset. Facial recognition systems generally already have a bias problem, often due to a lack of diversity in datasets. If datasets don’t reflect the deepfakes that need to be detected, more synthetic images may slip through the cracks as the issue snowballs.

Though this patent seemingly has good intentions, Green noted, this tech includes a system that labels images by race. However, race and ethnicity aren’t always easily detectable by just looking at an image, Green noted. For example, a system like this may fail to identify deepfakes of people who are mixed race, he said. “It’s a simplification of human diversity that could be ethically problematic.”

However, this isn’t the first time Intel has sought to patent systems to aim to make AI more reliable and responsible. Though the company’s primary business is making chips, it could be trying to give AI – and, in turn, itself – a good reputation, Green added.

“If AI in general gets this bad name because of deep fakes or other unethical behavior, then that could perhaps cause a backlash that would go all the way back to the chip industry,” Green said.

IBM’s Data Shakedown

IBM wants to keep its machine learning models from taking in junk data.

The tech firm is seeking to patent a system for protecting a machine learning model from “training data attacks,” IBM’s tech aims to keep AI models from sucking in public data that have potentially been compromised by bad actors.

“Attackers may manipulate the training data, e.g., by introducing additional samples, in such a fashion that humans or analytic systems cannot detect the change in the training data,” IBM noted. “This represents a serious threat to the behavior and predictions of machine-learning systems because unexpected and dangerous results may be generated.”

IBM’s tech aims to thwart this kind of threat by essentially applying a magnifying glass to the kind of data these models consume. To break it down: This system starts by initially training a machine learning model on a set of “controlled training data,” in which high-quality and reliable data is carefully selected for the task at hand.

After the first round of training, the system turns to the larger pool of public data to identify which of it may be “high impact,” or which data points may have a larger sway on the model during training.

Once the system identifies those data points, it creates an artificial “pseudo-malicious training data set” using a generative model. This set of data will essentially train the model on what attacks it may expect, so that it “may be hardened against malicious training data introduced by attackers.”

Data is basically the DNA of an AI model: Whatever it takes in is fundamental to what it puts out. So if a model is taking in tons of bad data – particularly data that may have a high impact on the model’s performance – then the outcome may be an AI system that spits out inaccurate and biased information, said Arti Raman, founder and CEO of AI data security company Portal26.

While smaller, more constrained models may not grapple with this issue, large foundational models that suck up endless amounts of data from the internet may struggle with this. And since the average consumer uses free and publicly available models, like ChatGPT or Google Gemini, over small ones, “It’s almost the responsibility of the model provider to make sure that those models don’t go off the rails,” said Raman.

“It’s pretty important to make sure that we have stable technology when it’s available to large populations,” she noted.

IBM’s system provides a way to defend large models from being tainted by a well of bad data, essentially acting as a vaccine against training data attacks. This method essentially builds “guardrails” into the model itself, allowing it to detect and fight against bad data when it comes across it, Raman noted.

Whether using this tech on its own models, licensing it out to others, or both, gaining control over patents related to strengthening foundational models could help IBM solidify its place among AI giants. “Everybody wants to figure out how to make models not misbehave,” said Raman. “So I think filing a patent is a pretty smart thing.”

The Future is Here – Stay Ahead of it with Gizmodo. Founded in 2002 as one of the internet’s very first independent tech news sites, Gizmodo’s free newsletter brings you comprehensive coverage on the biggest and most important businesses driving tech innovation such as Nvidia, Tesla, and Microsoft. Add Gizmodo to your media diet – subscribe for free here.

Extra Drops

- Apple wants to help its AI models see a little better. The company filed a patent application for a way to train a machine learning model to identify the “moment of perception” of a specified object in a video.

- Block wants you to cash out. The Square parent company filed a patent application for a system for “rewards for a virtual cash card.”

- Google wants to take a poll. The company is seeking to patent a system for “recognizing polling questions from a conference call.”

What Else is New?

- Google fired 28 employees after several protests over the company’s cloud contract with Israel and labor conditions.

- Startup Stability AI cut 10% of its staff, or around 20 employees, as a way to “right-size” the business.

- Cisco debuted a new AI-powered security system called HyperShield, aimed at protecting data centers and cloud computing.

Patent Drop is written by Nat Rubio-Licht. You can find them on Twitter @natrubio__.

Patent Drop is a publication of The Daily Upside. For any questions or comments, feel free to contact us at patentdrop@thedailyupside.com.