Sign up to unveil the relationship between Wall Street and Washington.

The American dream is not an elusive unicorn, tossing its mane, fobbing us all off and retreating devilishly into the mists.

Yet you could be forgiven for feeling that way, as the nation’s economic headwinds are starting to look a lot like a Hieronymus Bosch hellscape.

Want to buy a home, or perhaps just upsize your living quarters? Prices are slowly easing from their pandemic peak, but the nation’s median home price still clocked in at a frothy $363,000 last month, according to the National Association of Realtors. That’s down from the high of $412,700 for a single-family home in the second quarter of 2022, but as median home prices go it is still likely to give sticker shock to an average American with a median salary of just above $56,000 a year according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Maybe you live in a city. The consumer price index for urban dwellers from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows the cost of shelter in U.S. cities pointing straight up to peak levels in the latest data. Shelter costs accounted for more than 60 percent of the increase seen in the latest CPI data, climbing at the fastest annual pace since 1982.

No matter how generous your salary, it is highly unlikely that it can match the upward trajectory of these historic spikes. Even if it did, the boost seen last year in employee wages is cooling down, moving back toward pre-pandemic levels. “Workers are losing the battle to get a better deal out of prices and wages,” proclaimed Quartz at the start of the year.

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve has continued to prioritize price stability above growth, hiking interest rates at the swiftest pace in decades in a bid to break the back of searingly high inflation – a move that also increases the chances of recession this year. Until inflation eases, this puts many Americans in a financial bind.

Setting aside the implications of the recent banking scare and all that comes with it, rising interest rates mean Americans will be forced to simultaneously pay higher prices on goods, services and housing, while facing higher credit and borrowing costs. And if a recession comes, it could get worse before it gets better. It’s no wonder Americans are clamoring for change from their elected leaders. But what can they do to empower themselves in the meantime?

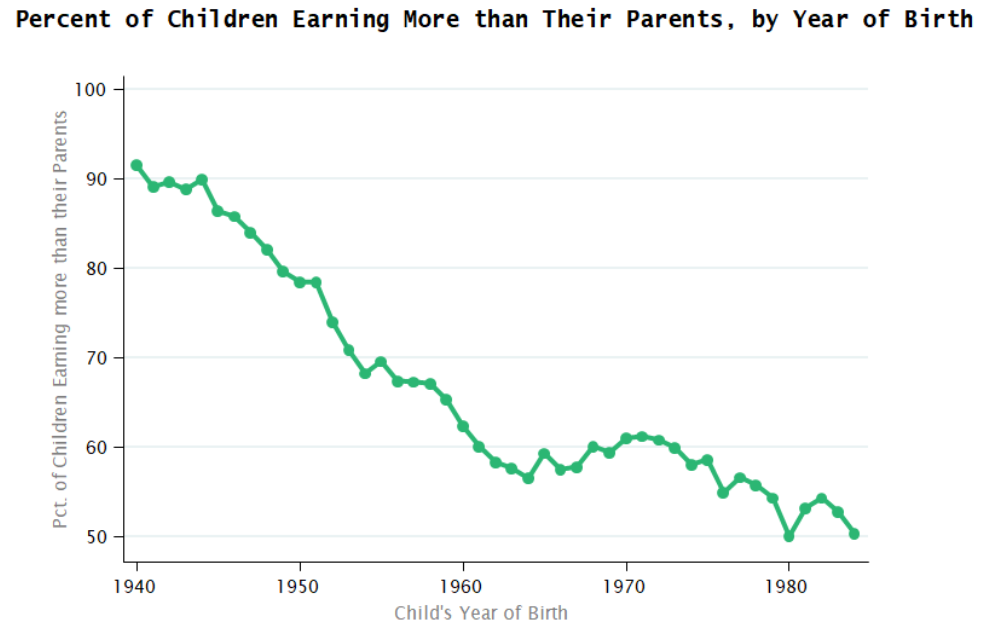

Enter a team of researchers at Harvard University with the Opportunity Insights project who have closely studied the American Dream and define it as “the fraction of children who grow up to earn more than their parents.”

Using big data, census records, anonymized tax returns and deeply granular information from cities, towns and neighborhoods across the nation, Opportunity Insights has learned that the American dream is, indeed, in serious trouble, with the data showing a particularly steep drop in the ability of children to earn more than their parents since the mid-1980s.

“We find that more than 90 percent of children born in the 1940s grew up to earn more than their parents,” the group notes. “But over the past 50 years, this measure of the American dream has been in decline. Today, only half of children grow up to earn more than their parents.”

From the high watermark of more than 90 percent in 1940, the number of children born in the 1950s who grew up to earn more than their parents fell drastically from just below 80 percent to just above 60 percent. From there, it dipped below 60 percent in the 1960s, with a brief leap above 60 percent in 1970, then dropping to 50 percent again in 1980.

During the mid-80s, the number of children who grew up to earn more than their parents ticked up again to around 55 percent but, since then, has slid to 50 percent, in a downward trend that is believed to have continued.

The latest data, which are longitudinal, stem from children born in the 1990s, reflecting their earnings as adults. As children born in the aughts come of age and begin to earn adult salaries, the Harvard project plans to update the data to keep tabs on the upward mobility of children reared across the U.S.

First, the data confirm the enormous difficulty of getting ahead for many Americans. But luckily, they also offer useful glimpses into how to hack the American dream.

Because the data cover the entire U.S. and allow you to drill down into specific cities, towns and neighborhoods, they can also show you key factors proven to boost the upward mobility of all Americans. Chief among them are the neighborhoods children grow up in and their “social capital,” which refers to an individual’s personal and professional networks and the kinds of relationships they are able to forge from childhood that may give them a leg up in life.

Labor market factors, quality of education, job markets, the upward mobility of neighborhoods, social capital and economic connectedness are major areas of inquiry for the Harvard research team. The goal: To use big data to gather powerful insights into what allows a child to achieve the American dream and to draw conclusions from strong statistical evidence that will help future generations, one of the researchers tells Power Corridor.

To illustrate which parts of the U.S. offer the greatest upward mobility for children born and living in those locations, Opportunity Insights built an interactive map called the “Opportunity Atlas.” For anyone rearing children, this is an excellent way to identify which parts of the country are historically the most upwardly mobile, depicting the likelihood of children born from parents of various income levels achieving the American dream in every part of the nation.

As a rule, children born from lower-income parents and reared in parts of the U.S. with lower historic mobility will have a harder time earning more than their parents and achieving the American dream. This is a primary focus of much of Harvard’s research, which is already putting the data to use, working with communities, practitioners, and policymakers to give lower-income families access to parts of the county identified as “higher-opportunity areas.”

One such project between academic researchers and public housing authorities in the Seattle area is conducting a program that has greatly increased the share of families able to move to higher-opportunity areas. While just a few years old, the project will be assessing how these families and their children make out over time, which could help inform other programs seeking to reduce the barriers lower-income families face and increase upward mobility.

The interactive map shows sweeping implications for middle-class and upper-income families as well, allowing users to get a detailed snapshot of the adult salaries of children growing up in states, cities, and towns across the country from a historical perspective. While such data cannot immediately undo the plight of many Americans, what it can do is empower them by providing the tools to determine the best places to live and rear a family from a statistical standpoint.

Among the most important characteristics of higher-opportunity areas known to help Americans achieve greater upward mobility include quality schools, outdoor spaces, access to resources, abundant transit options, and a thriving jobs market. How these characteristics might be manifested in lower-opportunity regions in the future remains to be seen, but is an area for further study.

Another big data study by Opportunity Insights highlighting a key factor in Americans’ upward mobility measured the social capital of 72.2 million anonymized Facebook profiles, combing through individuals’ relationships and social interactions.

Assessing these against tax records, neighborhood data, and census records, Harvard researchers were able to track cross-class integration and chances for forming meaningful relationships among people of varying incomes.

The verdict: People with higher incomes tend to have higher-income friends, while people with lower incomes tend to also stick together.

These social networks from childhood, school, university, and beyond have a major impact on an individual’s upward mobility. Such relationships, according to Harvard researchers, determine economic connectedness, which has a high correlation to upward mobility.

So, if you want to earn more, check out the map – then dust off your black book.

Power Reads

Some of our favorite recent reads, for your weekend adulation.

Remember when Credit Suisse (before it was a recently collapsed bank forced to merge with UBS) entered a plea deal in 2014 with the U.S. government to stop helping wealthy Americans cheat their taxes? Well, it looks like it had its fingers crossed. CNBC’s senior Washington correspondent Eamon Javers uncovered an excellent scoop on how Credit Suisse, in violation of its agreement, went right back to helping rich Americans dodge their taxes by hiding their accounts under the names of Italian cities (in one instance) and even encouraging Americans to get alternative passports and citizenship to avoid paying their fair share. A great, infuriating read.

In a perfect corollary to the Credit Suisse story, Quartz’s Tim Fernholz writes about an unusually large, $7 billion tax payment made under the category of “estate and gift” taxes to the U.S. Treasury following what appears to be the death of a mysterious, unnamed billionaire. He asks, in this money-obsessed culture we all live in, “Can a billionaire die without anyone noticing?”

A mind-expanding piece out from the Atlantic’s Marina Koren examines the ongoing quest of astronomers to find a planet like our own and any signs of alien life. “One promising planet turned out not to have an atmosphere. But there are six more where it came from,” she notes. It also seems certain parts of the solar system have been identified as more promising for sustaining life than others, so the hunt may be narrowing. Another sign the odds might be in our favor that life exists off Earth. (My question: Are we ready for it?)

Power Corridor is written by Leah McGrath Goodman. You can find her on Twitter @truth_eater. You can also find Power Corridor @PowerCorridor_. Power Corridor is a publication of The Daily Upside. For any questions or comments, feel free to contact us at admin@thedailyupside.com.

The views expressed in this op-ed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of The Daily Upside, its editors, or any affiliated entities. Any information provided herein is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as professional advice. Readers are encouraged to seek independent advice or conduct their own research to form their own opinions.