Amazon AI Alexa Patents Highlight Data Collection Domino Effect

Two patents from Amazon signal Big Tech’s desire to give consumers the benefits of AI by getting under their skin.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

Amazon may want Alexa to hear and do more.

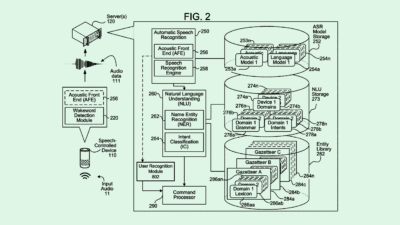

The company filed two patent applications detailing ways to make its virtual assistant more useful. To start, Amazon is seeking to patent a way to collect “multi-session context.”

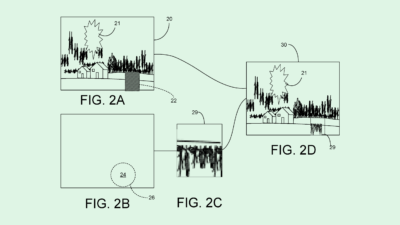

Amazon’s tech stores user data upon initial interactions, including “action data,” or information about user behaviors, “entity data,” or data related to the user, and a profile identifier. The system then holds onto that data for subsequent interactions and uses it to modify responses.

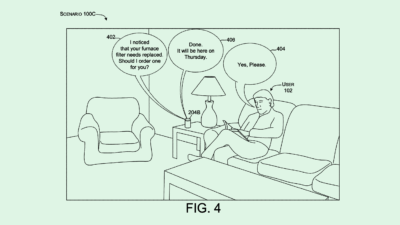

For example, if you ask Alexa to place an Amazon order for a certain product, it may access stored information from previous discussions relating to brands, sizes, or product details. If a user requests that Alexa play “party music,” it may access stored data relating to previously requested songs. Storing previous dialog information in this way may help in “moving the dialog along in a manner that results in a desirable user experience,” Amazon said.

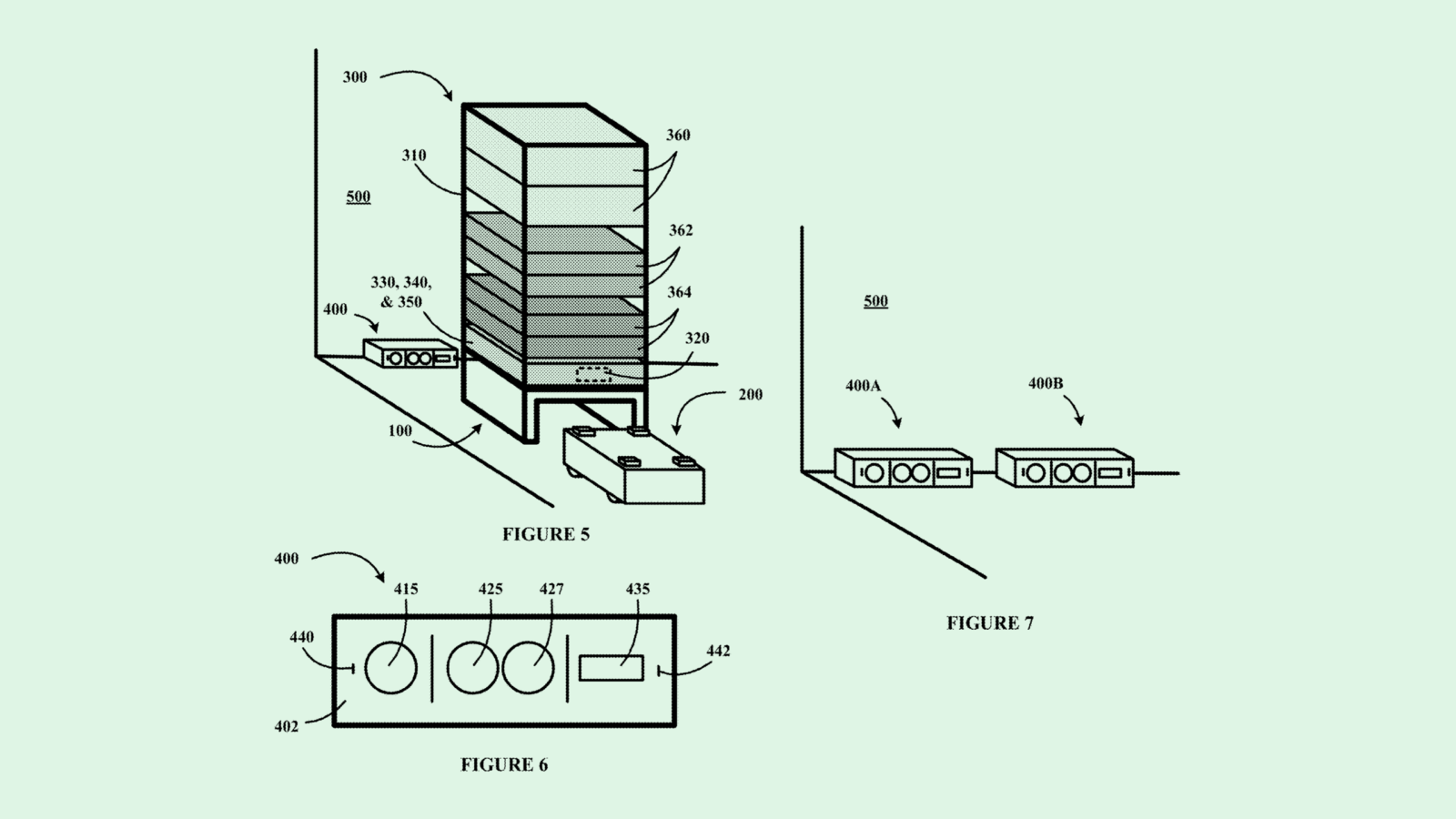

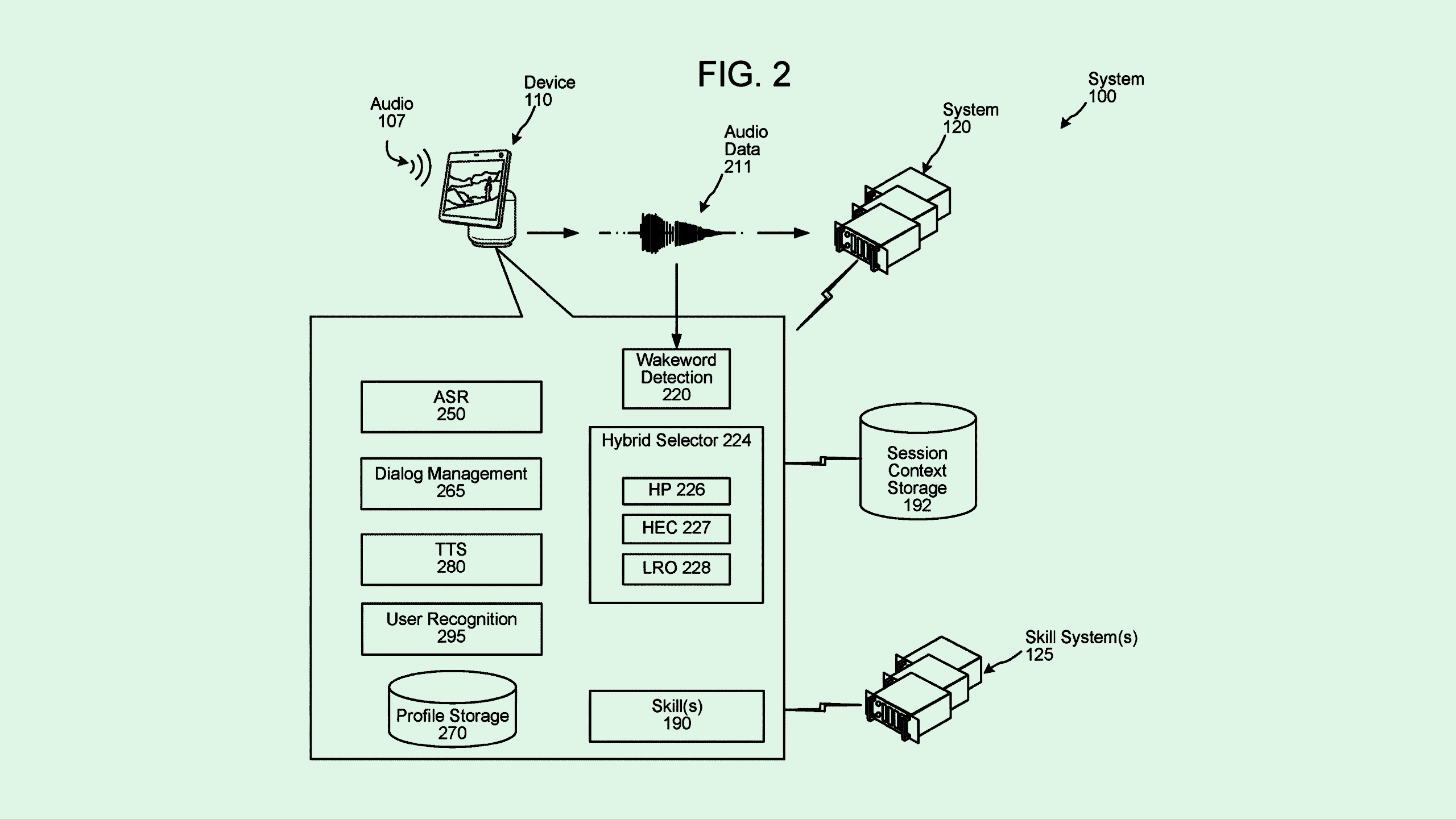

Along with teaching its virtual assistant active listening, the company may want Alexa to multitask with a patent for “multiple skills processing.” As the title of this patent implies, Amazon’s patent aims to help its assistant perform “complex goals” using multiple skills and applications.

With a user’s permission, data is forwarded between applications to perform different requests, “even if the other action for the other skill was not necessarily requested by the user,” the company said. “Thus the system enables the system to perform multiple actions and the user to initiate multiple skills with fewer user inputs.”

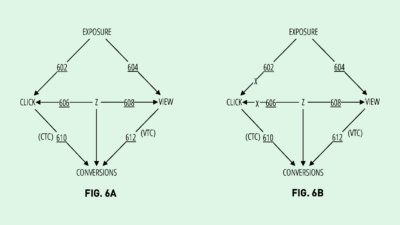

Amazon’s patents point to a common theme as AI adoption continues to ramp up: Context is key. The more user context an AI model has to work with, the more it can do, said Bob Rogers, PhD, co-founder of BeeKeeperAI and CEO of Oii.ai. “The most annoying thing is an AI recommendation that really doesn’t make sense,” he said.

Obtaining more context allows a system such as a virtual assistant to better connect the dots, understanding the patterns of a user’s day-to-day life. That data ultimately could be used for Amazon’s financial benefit, said Rogers, allowing it to find gaps in user’s lives and make recommendations accordingly.

“If they are able to create a sort of ongoing series of meaningful threads and context about the people who are using these systems, they’re going to have something very powerful,” he noted.

Plus, giving these tools more insight ultimately makes them more useful, said Rogers. And with competition from the likes of Google (and now Apple) in the consumer AI market, adoption is likely front of mind for Amazon.

However, the question of privacy versus utility always looms when discussing consumer AI. Though the average consumer struggles to trust AI, these tools are often not explicitly marketed as such. Plus, Rogers said, if the convenience matches or outweighs the data trade-off, consumers aren’t likely to care. “(Amazon) knows about what we watch on TV, they know what we buy, they know when we’re home,” he said. “I don’t think privacy concerns are going to stop people from adopting the tech.”

“If you ask someone if they’re concerned about data privacy, they’ll say yes, but when it comes to making a decision about clicking ‘yes’ on an end-user license agreement, they don’t really read the details,” Rogers added.

These patents also highlight the growing level of automation that tech firms want, said Rogers. Think of it like a domino effect: While the tech may start by collecting one kind of data or accessing just a few apps, it may be hard to tell where the line is drawn if that convenience grows. “(The patent) feels like they’re thinking about Alexa capabilities, but truly, these things always ended up being ecosystems,” said Rogers.