Into the Future: The Patent Drop Highlight Reel

What the years of writing about Big Tech’s IP has taught us.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

We’ve learned a lot writing about the IP landscape of Big Tech the past few years. In tearing through thousands of patent applications, a few common themes have stuck out. To put it simply, everything – from consumer tech to logistics to enterprise to vehicles – is getting smarter. And everyone – from Google to Microsoft to Nvidia to Meta to Ford – wants a piece of this future.

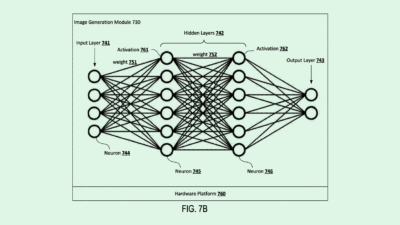

AI every which way

You’ve probably heard about this crazy little thing called artificial intelligence. If poring through patent applications has revealed anything, it’s that every big tech firm wants in.

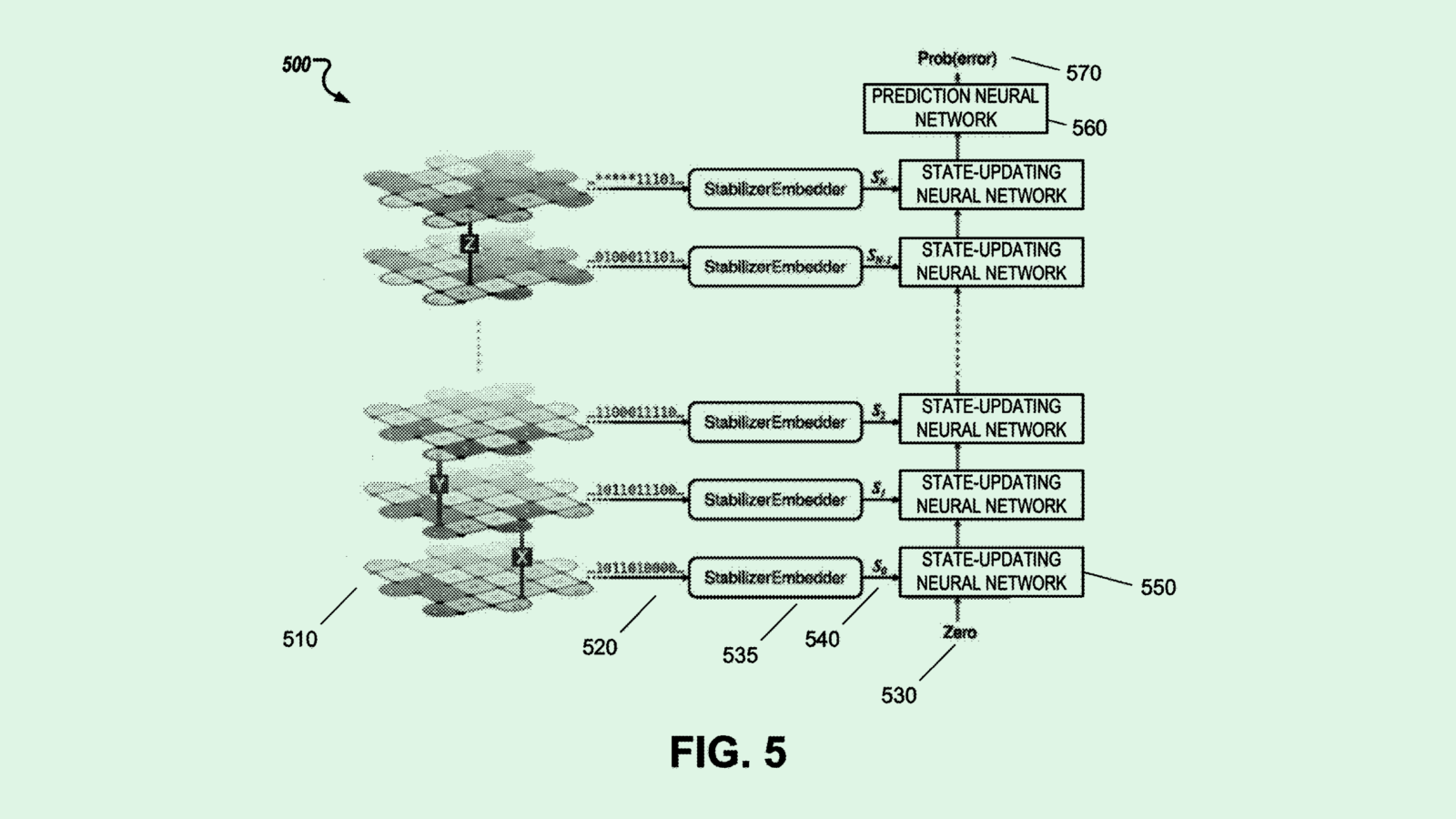

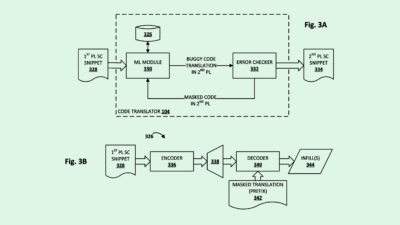

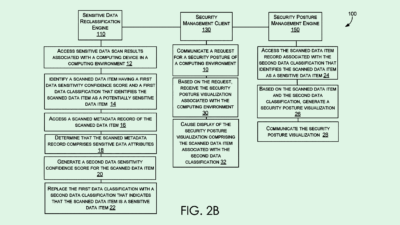

Often, their innovations focus on ways to fix AI’s fundamental problems. For example, Adobe, Microsoft, and Nvidia have sought to patent different ways to minimize hallucination and inaccuracy, a problem that continues to plague AI developers. Patent requests from IBM and Intel have taken on the issue of bias, while Google, Meta, and Palantir have applied to patent solutions to AI’s data-security problem.

Additionally, these inventions often aim to make adoption safer and easier, tackling ethical risks, explainability, energy efficiency and low- to no-code development.

Taken together, these patents offer a snapshot of companies scrambling for an edge in an industry growing at a breakneck pace.

Eyes on the Enterprise

After plunging millions into AI, lots of companies are still navigating how, exactly, to monetize it. Patent applications like these have revealed that many tech firms have their eyes on enterprise integrations as a means of doing so.

Companies often target cybersecurity, with patents tracking dysfunctional devices or cloud breakdowns putting AI’s talent for rapid pattern recognition and monitoring to work. Productivity is another major niche, as demonstrated in Deepmind’s patent for a generative AI coding tool; Microsoft’s customized data analysis tech; and Oracle’s AI model-generating chatbot.

Sometimes, however, these inventions walk a fine line between keeping tabs on the workforce and over-surveillance, like Zoom’s engagement analysis tech; Snap’s emotion detection patent; Google’s burnout-tracking keyboard and Microsoft’s email “tone detection and suggestion” patent.

Privacy versus Convenience

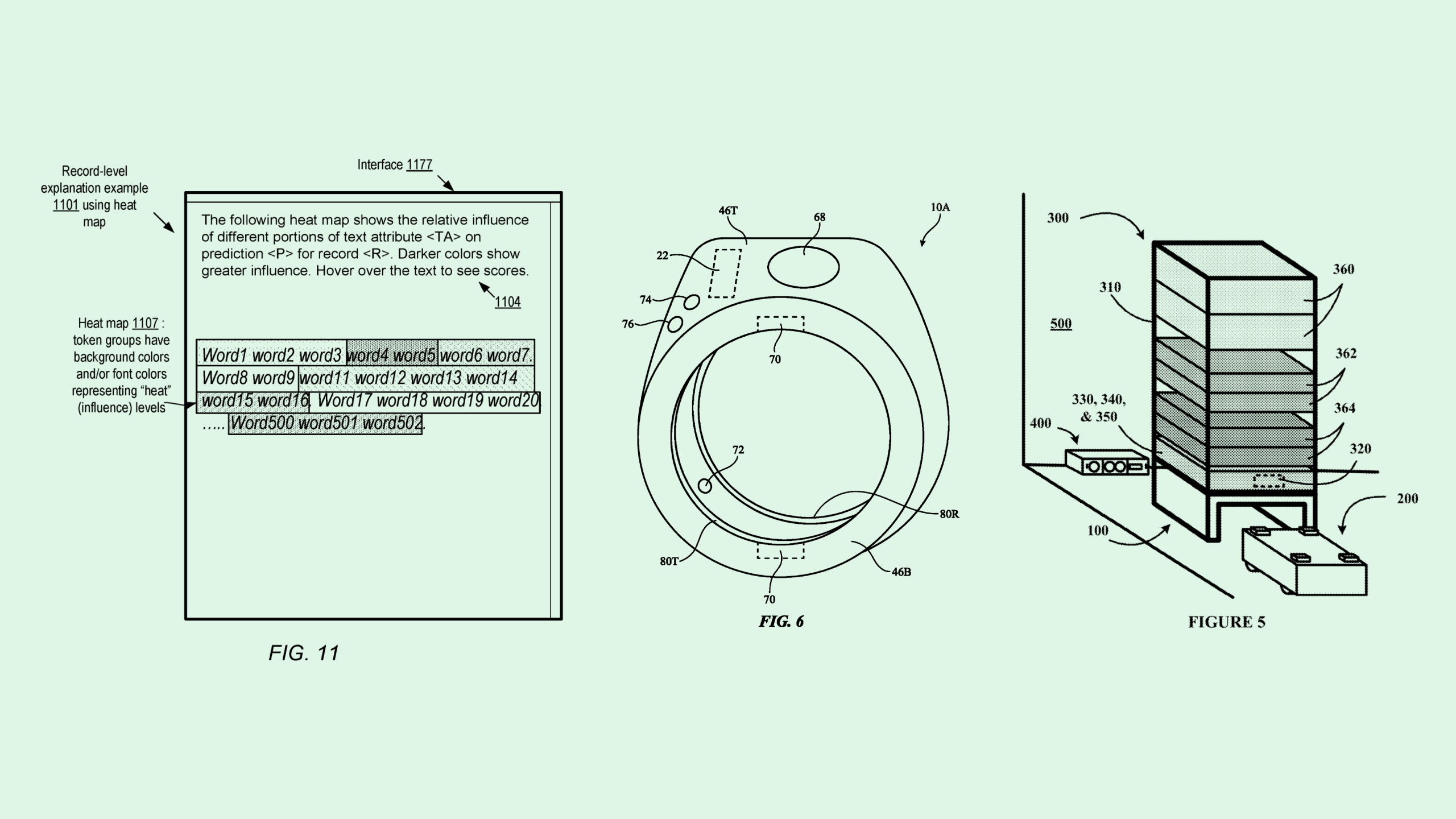

When looking at the world of consumer technology, one of the biggest trends that patents highlight is a focus on wearables, running the gamut from smart watches to rings to AR and VR headgear to chest-worn pins. The common thread is that they’re inching closer and closer to users with each innovation.

Meta’s patent history, for example, includes IP for “skin vibration” tracking and brain signal reading. Apple, meanwhile, has sought to patent a biometric tracking ring and a health-sensing band for the Vision Pro, and Snap has filed a patent application for AR/VR-enabled contact lenses.

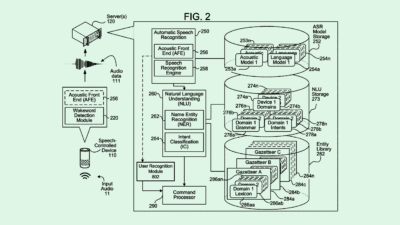

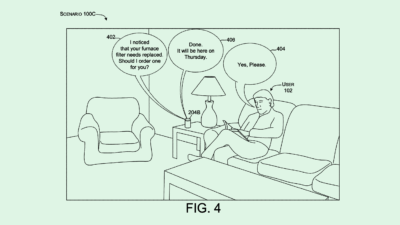

Beyond wearables, companies are keenly interested in getting to know us better via our Internet-of-Things devices like smart home speakers, appliances, phones, and laptops. Amazon has filed a number of patents to make its Alexa smart speakers more contextually and emotionally aware. Google has patent applications that have sought to get rid of wakewords by making its AI assistants more observant. Microsoft previously filed a patent for an observant, AI-powered backpack, and IBM tinkered with a way to track users via their appliances to time ads.

The innovations let these companies get to know their users, which of course cuts two ways. While this is certainly a benefit for a consumer interested in getting a more personalized experience out of their tech, it begs the question of where the average user would draw the line between privacy and convenience.

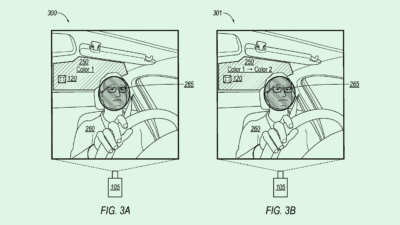

Autonomous Everything

From drones to robotics to vehicles, tech firms of all shapes and sizes really seem to care about making machines that can operate themselves, both in enterprise and consumer contexts.

These patents often pitch ways to support (or supplant) human labor, such as Amazon’s factory logistics robots, Ford’s automated vehicle maintenance tech, eBay’s drone delivery, or Intel’s adaptable “collaborative robotics.”

A lot of autonomous IP, however, focuses on giving these machines better eyes, such as Tesla’s fix for phantom braking, Google’s patent for robotic attention estimation, or Nvidia’s tech to make robots more proactive. Why? Because in order to actually integrate these machines into our everyday lives, developers need to get accidents and mistakes down to a minimum.

Improving reliability of autonomous machines could be the key to unlocking higher adoption rates. For self-driving vehicles, this may mean easing pressure from regulators like the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which has brought the hammer down on Tesla, General Motors, and Ford in recent years. For enterprises, this could help get closer to a “lights-out” production model, replacing human labor on factory floors.

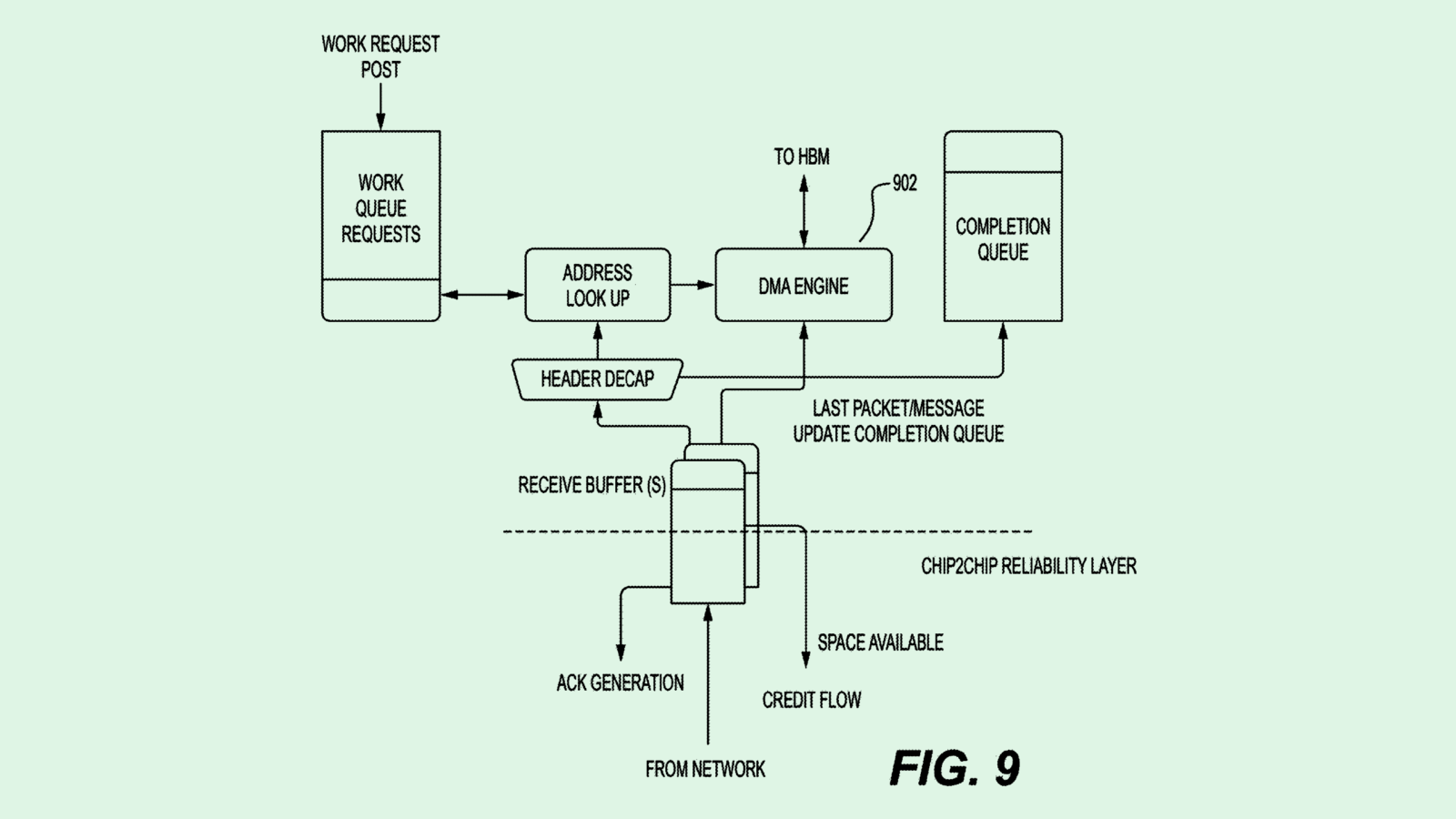

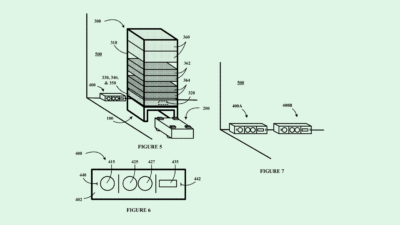

The Next Data Center

Amid the AI boom, the rapidly growing need for computational power has taken center stage. That has sparked a desire from big tech companies to reimagine data centers.

Lots of these innovations target data-center energy efficiency as AI development continues to gobble up power: Intel sought to patent a way to assign tasks based on emissions estimates; a filing from Google details a way to forecast carbon-intensive demand periods; and Nvidia filed for a patent on technology to power down underutilized resources to save energy. A few filings from Microsoft are even more outlandish, pitching direct air capture and cryogenic cooling in conjunction with these server farms.

Energy efficiency and emissions aside, many filings seek to innovate the way that data centers operate, such as Google’s patent request for environmental-sensing drones; Nvidia’s patent application to use robots to manage server racks; Microsoft’s plan to sublet computing power to spin up on-demand “cloudlets;” or IBM’s pitch to utilize the computing resources of autonomous vehicles.

Each of these patents could allow companies to shape what the next generation of data centers may look like – whether these ideas be implemented in their own facilities or used to show thought leadership (and sell more chips).

Blockchain ≠ Crypto

While blockchain is the core technology that makes crypto run, the tech itself is capable of a far wider array of use cases than digital currency.

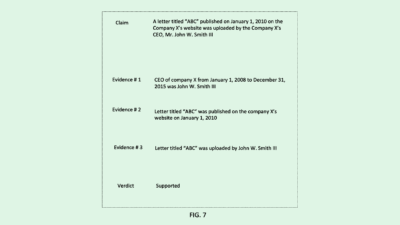

The transparent and immutable nature of blockchain makes it a great fit for security and fraud-tracking applications. For example, a JPMorgan Chase patent seeks to use the tech for fact verification; Sony may use blockchain to trace deepfakes; and Mastercard looked into blockchain as a means of reducing ticket scalping.

Other companies’ patents rely on this tech as a means of record-keeping and identity security. Visa, for instance, sought to patent a blockchain-based “universal record” system for any personal information a user may need. Okta, meanwhile, researched ways to use blockchain for one-time passwords.

Interest from major tech and finance firms could help separate core blockchain technology from crypto’s volatility in the public eye.