Big Tech Has an Energy Problem

How tech firms reconcile their desire for endless growth with bold climate goals.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

As climate change looms ever larger, the climate goals of many tech firms seem to get loftier.

Almost every tech titan seemingly has a goal to drastically cut carbon emissions by the end of the decade. Microsoft wants to be “carbon negative” by 2030, and remove the amount of carbon the company has emitted during its lifespan by 2050. Google and Meta have similar goals, aiming to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030. Nvidia wants to use 100% renewable energy for Scope 1 and 2 operations by 2025.

Even companies focused heavily on consumer products are looking at how to slash products, such as Amazon’s goal to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2040 and Apple’s plan to become carbon-neutral by 2030 by pressuring isuppliers to clean up their processes.

These companies are touting a variety of ways they plan to cut their carbon footprints, ranging from clean manufacturing to carbon capture to internal initiatives like “all-electric kitchens.” But Big Tech’s ambitious climate goals face a reckoning with their sky-high power usage, experts told Patent Drop.

“Ultimately, Big Tech is using a lot of energy,” said Dr. Daniel Stein, founder of Giving Green. “Data centers are energy-intensive, running these big AI models uses a lot of computing. They are just in an energy-intensive industry.”

The Data Center Problem

A major energy hog is the tech industry’s demand for data centers. These massive server facilities need a huge influx of energy to stay cool and keep cloud services running. According to the Department of Energy, data centers take up 10 to 50 times more energy than an average commercial office building, representing 2% of all energy usage in the US.

The AI boom only serves to worsen the problem, said Greg Smithies, partner and co-lead of the climate technology investment team at Fifth Wall. The push for AI is leading to growing demand for data centers: A report from commercial property consultancy Newmark found that data center energy usage is likely to more than double in 2030 from 2022.

This demand has “basically thrown that entire (net-zero) equation out the window,” said Smithies. “I would not be surprised if we see a lot of these firms actually have to re-evaluate their ESG goals. I don’t actually see any way that the back-of-the-envelope math works out so that they can get there and in an AI growth scenario.”

Patent activity over the past year signals that tech firms seem aware of the obstacle that these server farms pose to their climate goals:

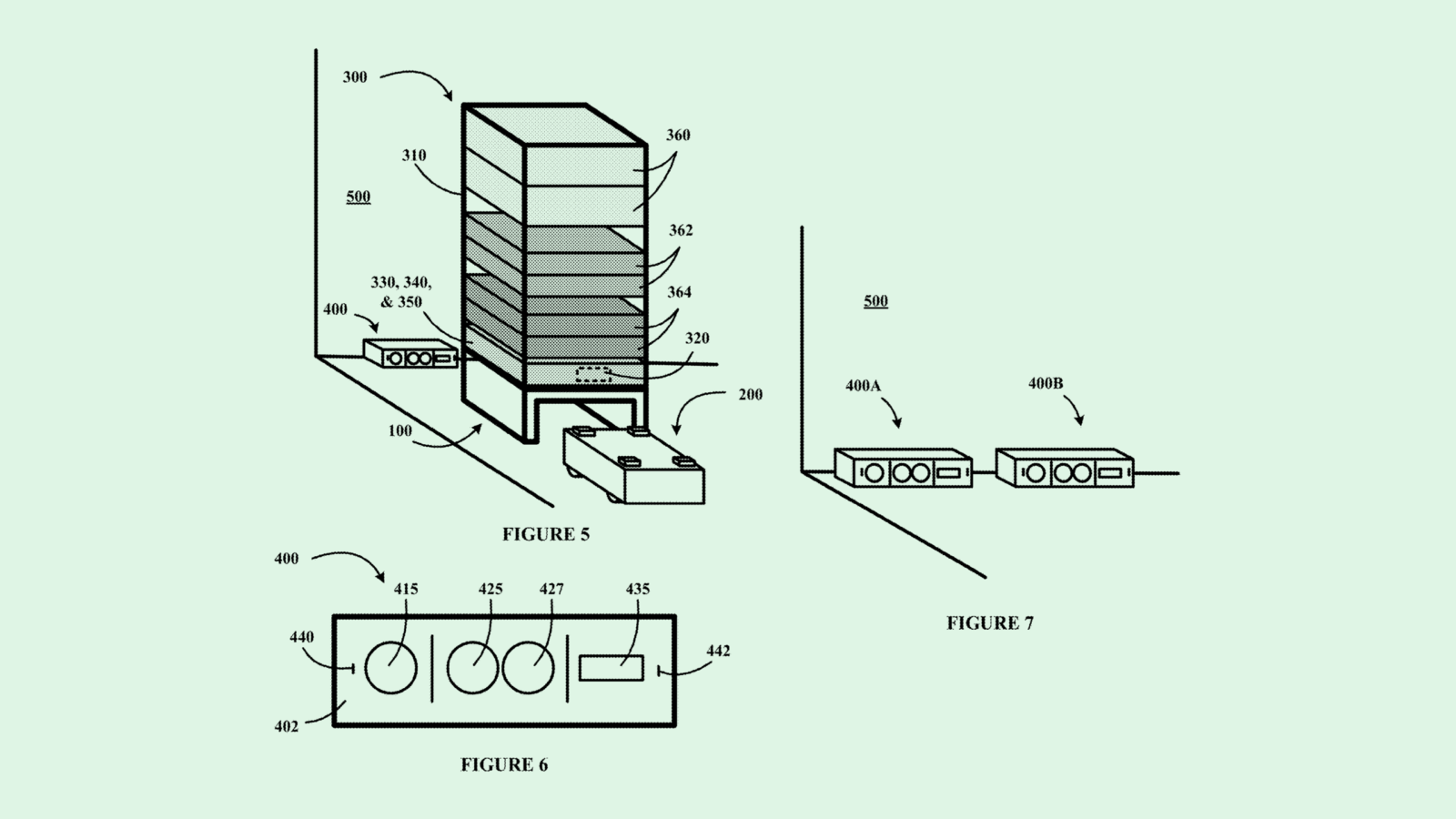

- Nvidia wants to patent a way to identify and power down “idle cores,” or underutilized servers that are wasting power in a data center;

- Intel wants to patent a system for “renewable energy allocation,” which budgets clean energy to specific high-intensity workloads;

- Microsoft similarly has sought to patent “sustainability-aware” device management, which measures how carbon-intense certain computing tasks may be;

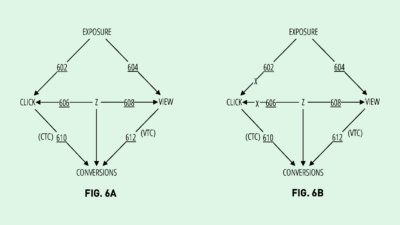

- And Google filed a patent application for its own system for “managing power in data centers,” which forecasts and mitigates certain operations that require lots of carbon-intensive energy consumption.

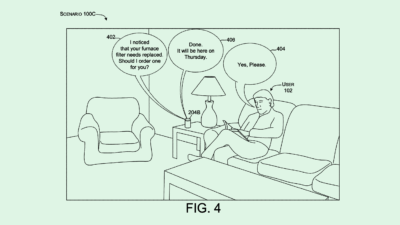

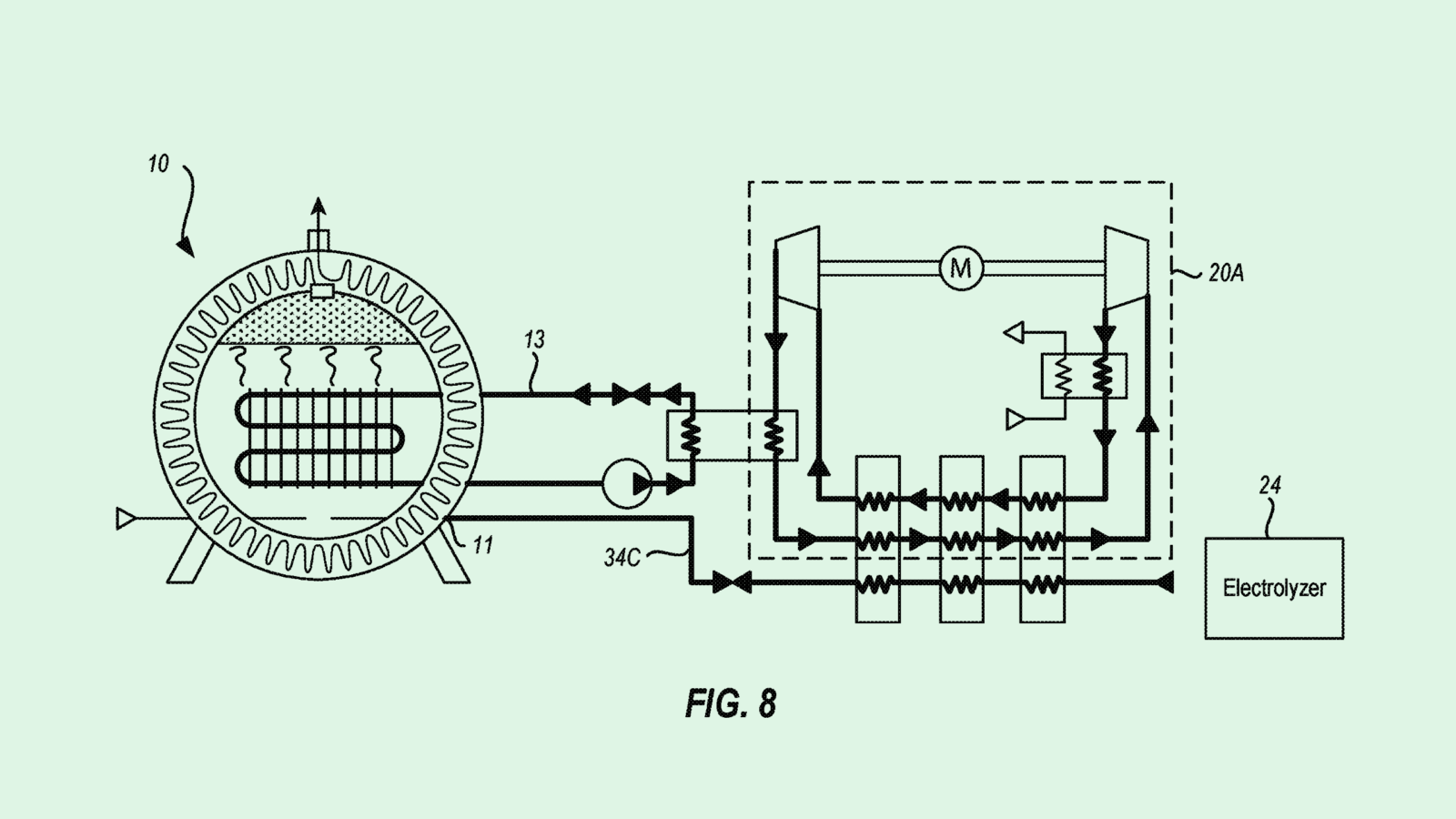

Microsoft may even be seeking ways to bring carbon capture into managing its data center emissions. Several of the company’s patent filings show research into using cryogenic energy both for “direct air capture” carbon removal and as a backup energy source in data centers.

Looking at energy optimization in this way can make a major difference to companies like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google that operate hundreds of data centers, said Evan Caron, co-founder of Montauk Climate. “I think there are a lot of process efficiency opportunities coming out.”

“No Silver Bullets”

The main options for renewable energy are solar, wind, hydroelectric, geothermal, and nuclear, none of which beat out nonrenewables which account for roughly 80% of all energy in the US. While energy management solutions aim to keep each of their own data centers in check, the bigger problem is that there simply isn’t enough renewable energy to reliably power these facilities at a constant rate. “The core technologies that exist today need to be scaled,” said Caron.

One option to support renewables is the classic battery. These are often only used as a backup in cases where few clean energy resources are available, Stein noted. But most of the batteries on the market only last around four hours, he said. And during a winter with little sun or wind, batteries may simply not cut it, leaving a data center without power and customers without service until the sun shines again.

A further backup for this is clean hydrogen, said Smithies. On a seasonal cycle, this kind of energy would be created during the summer when there is an excess of solar energy, which is used behind the scenes to split water molecules to create hydrogen to “throw into your tanks for the middle of winter.” The farther-out version of this is geologic hydrogen, in which hydrogen is pulled directly from the earth and used as green fuel, Smithies said.

Finally, there’s the nuclear option. While large-scale nuclear facilities have been around for decades, several in the clean energy space have talked about building small ones the size of a few shipping containers, known as small modular reactors. However, building these reactors at scale is still several years off due to the high price tag, complex design, and a lack of engineers focusing on the issue, Caron noted. Compared to when nuclear first came into the fold in the mid-20th century, “We just don’t have the same level of attention to education around (nuclear) engineering.”

Every option to bridge the gap between clean and dirty energy has its pitfalls, said Smithies, “Unfortunately there’s no silver bullets here,” he said. “We’ve kind of got to do everything.”

Net-Zero Tunnel Vision

Big Tech firms have the resources to make massive changes by investing in these technologies, said Stein, but it may require them “doing things beyond just their value chain.”

A common option is plowing money into carbon credits. But carbon offset markets are often unreliable, said Stein. And at the end of the day, carbon credits don’t reduce the amount of carbon that a company actually emits – it just reduces their responsibility for that carbon. “We need to get down to zero emissions as a globe,” said Stein. “So at some point, if you have a company that’s emitting there’s going to be no one to pay (for carbon credits).”

Companies could do a lot more by looking beyond the net-zero paradigm. Putting their money towards decarbonizing their operations and suppliers with green technology, investing in high-impact funds focused on scaling climate tech, or getting involved in climate policy stands to make a much bigger difference, Stein said.

“You could have an impact way beyond your little net-zero footprint,” said Stein. “You could do much better than buying carbon offsets.”