Google’s Watchful Doorbell Patent Highlight Tech Companies’ Interest in Surveillance

Google’s Nest doorbells might be joining the neighborhood watch. The patent signals that people are growing more comfortable being watched.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

Google may be getting into the neighborhood watch.

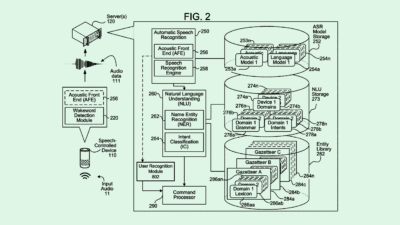

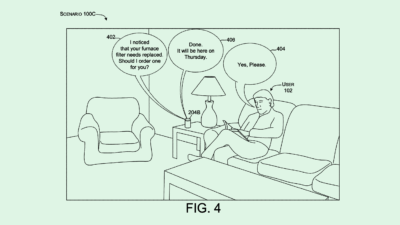

The company is seeking to patent a system for “detecting and responding to a visitor in a smart home environment.” Google’s tech is essentially an everything doorbell, with the ability to recognize who’s at your door, why they’re there, and perform actions while the occupants are safely tucked away inside.

While existing technologies offer a single alert for users at the door, “a single type of alert is not appropriate for all detected persons,” Google said in the filing. “Some persons may be welcome guests, occupants, unwelcome visitors, or merely persons passing by the entryway.”

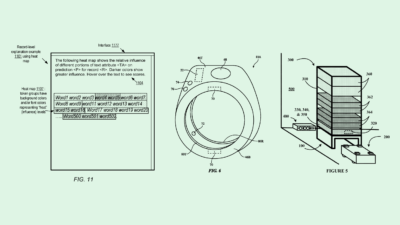

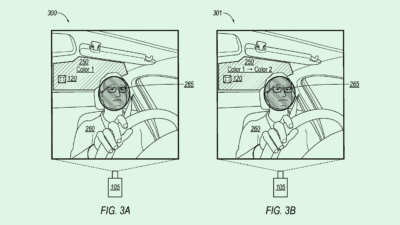

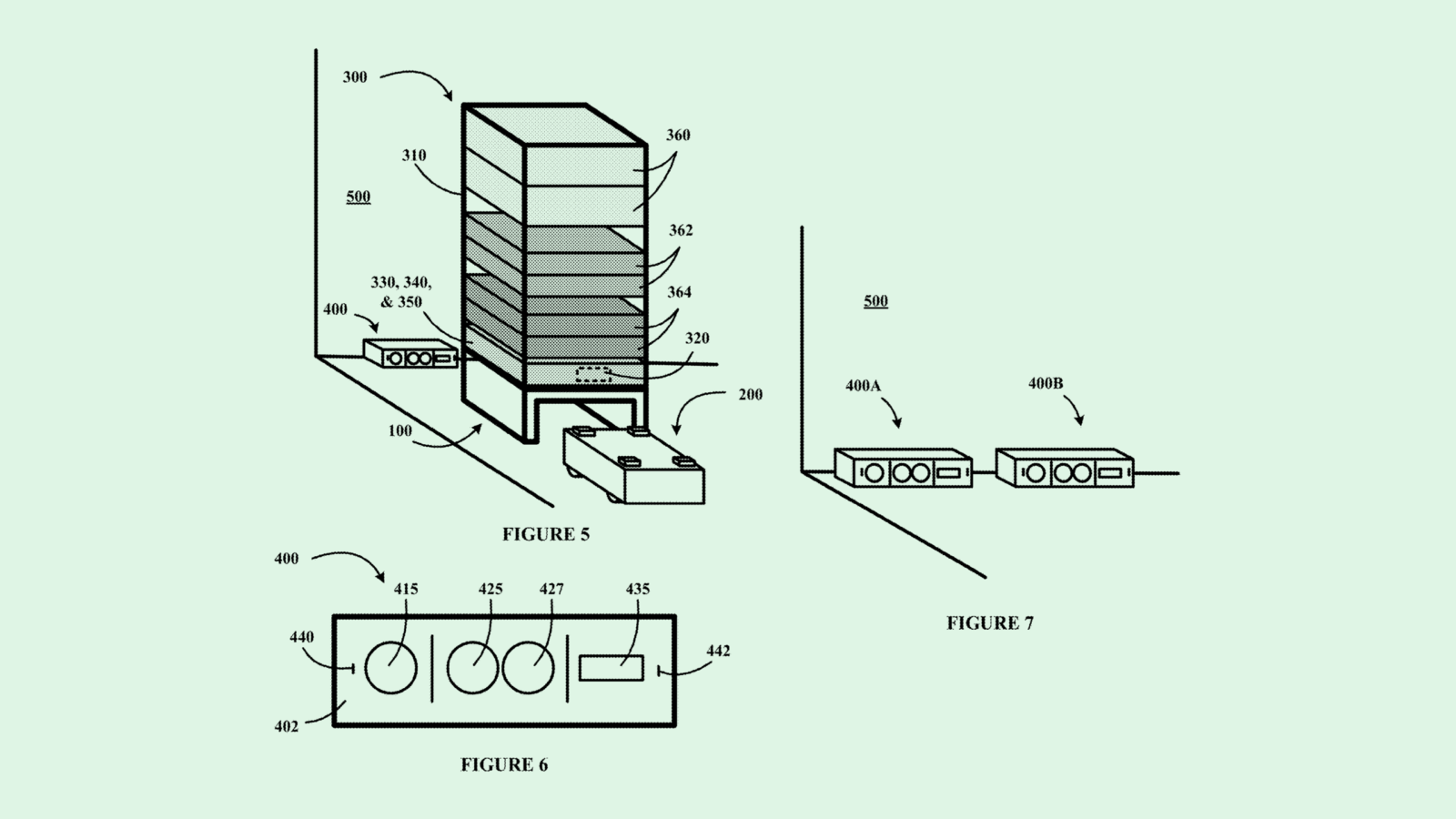

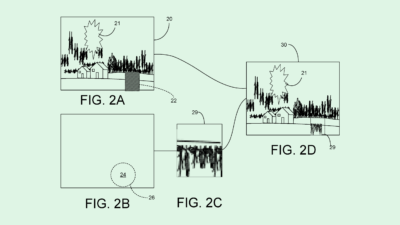

Here’s how it works: When a visitor first approaches a home, Google’s robo-doorbell starts by initiating facial recognition on the visitor to determine if they are known to the occupant, and launches what’s called an “observation window” before a user reaches the “physical interaction area” of the entryway. The doorbell learns familiar faces over time through facial recognition of common visitors.

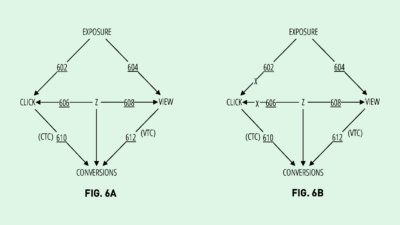

During that observation window, Google’s system obtains “context information” about why a user may be there, using physical, behavioral, motion and timing information. From this, the system either initiates actions or gives the occupants recommended actions to take.

For example, If a delivery person comes to the door, Google’s system can either say “leave the package on the porch,” or give the occupant the opportunity to speak to the deliverer through a speaker on the doorbell. If a stranger approaches that Google’s system deems dangerous, the system can automatically say “warning: you are under surveillance,” and offer a quick action button on the user end to call the police.

Google’s system can also determine that someone is simply walking past the door without meaning to approach the house, so as to not bombard the occupant with motion sensor alerts.

Google offers familiar face recognition as a part of its Nest doorbell system, but this patent seemingly goes beyond its current capabilities. And these devices highlight a troubling trend seen with a lot of different inventions tech companies are researching: People are getting more comfortable with increased surveillance for the sake of perceived security and convenience, said Calli Schroeder, senior counsel and global privacy counsel at EPIC.

“I think we’ve stopped really taking stock of whether what we’re getting for this surveillance is worth what we’re giving up,” Schroeder said.

Determining intent and context, especially for in-person interactions, is not an easy task for an AI-based system to do and hasn’t yet been done flawlessly, Schroeder said. And, as is the nature of AI, it can take on the characteristics and biases of both the people that train it and the people that use it. Plus, Schroeder said, facial recognition is particularly bad at accurately identifying people with darker skin tones, as well as gender recognition with transgender and nonbinary people.

“The populations that are most likely to be misidentified or wrongly identified by these systems are some of the most vulnerable populations to violence and aggression already,” she said.

While the tech in this patent has some good use cases, those circumstances are “extremely limited,” Schroeder said, and it could do more harm than good. Along with potentially targeting people with biased facial or intent recognition, this tech may lead to unintended surveillance of non-consenting passersby, especially if placed in apartment buildings where people are constantly walking past.

Big Tech’s stake also shouldn’t be ignored, Schroeder noted. Google has had a number of run-ins with data privacy issues in the past. And Nest competitor Ring, owned by Amazon, has gotten in trouble for employees spying on customers.

“Those recordings don’t just go into the ether,” said Schroeder. “I’m sure Google and many other companies would say they have internal policies about who can access these systems, but as we’ve seen in other circumstances, that can be misused.”