Meta Patent Seeks to Track Users’ ‘Biopotential’ Signals

While wrist-worn controllers may be the next frontier of artificial reality technology, it’s likely not the end goal for AR control.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

Meta wants to take the friction out of artificial reality.

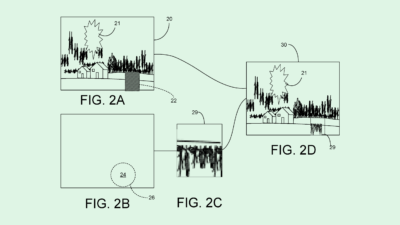

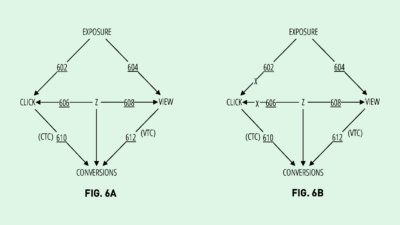

The tech firm is seeking to patent what it calls an “easy-to-remember interaction model” for using artificial reality headsets, relying on in-air hand gestures for control. Meta’s tech tracks “biopotential signals” from a user’s movements and body to interpret gesture data with higher accuracy.

“Techniques for interacting with wearable electronic devices can be cumbersome and/or impractical at least because they cause inefficient use of computing resources and/or energy capacity at the wearable electronic devices,” Meta said in the filing.

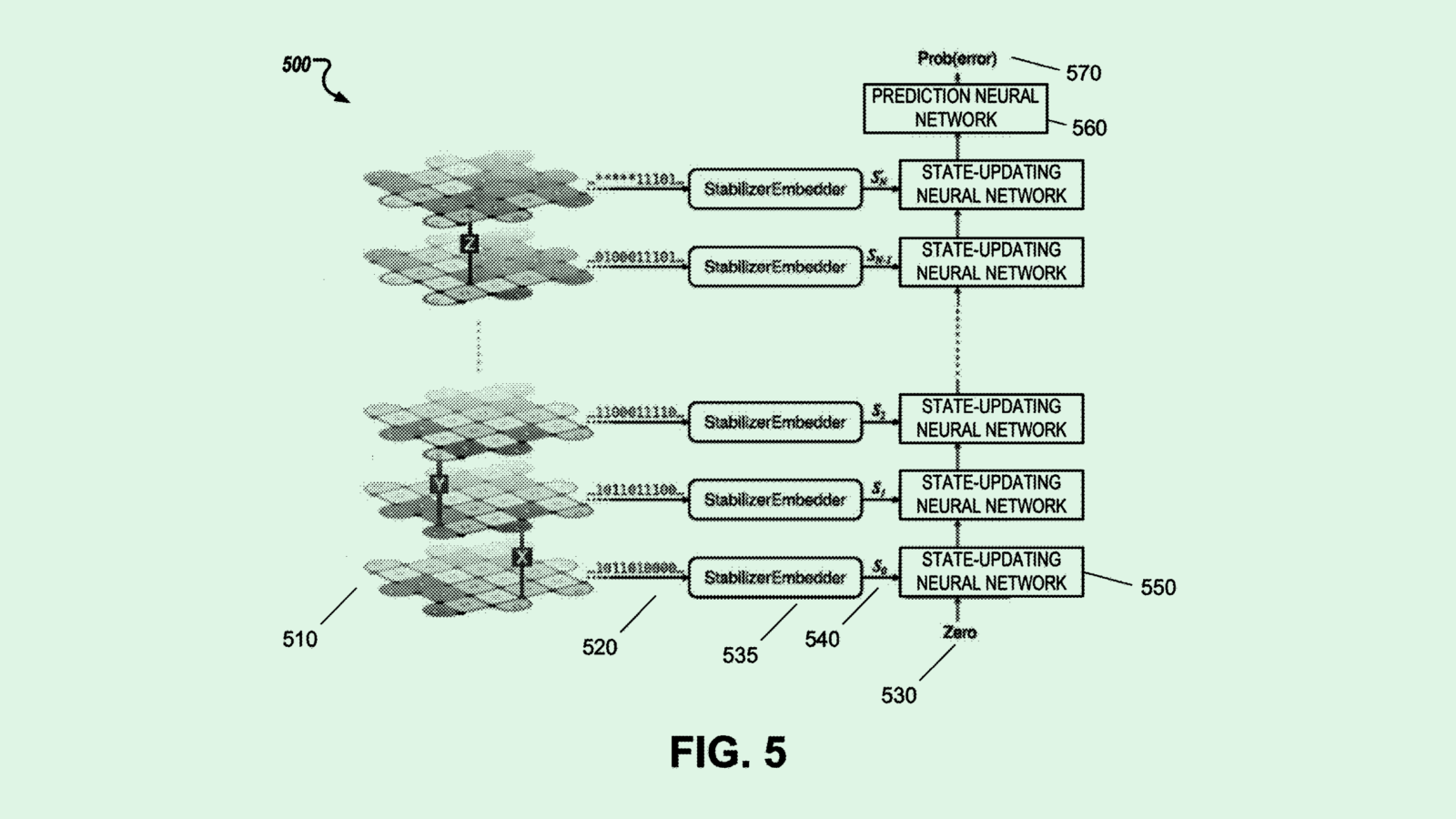

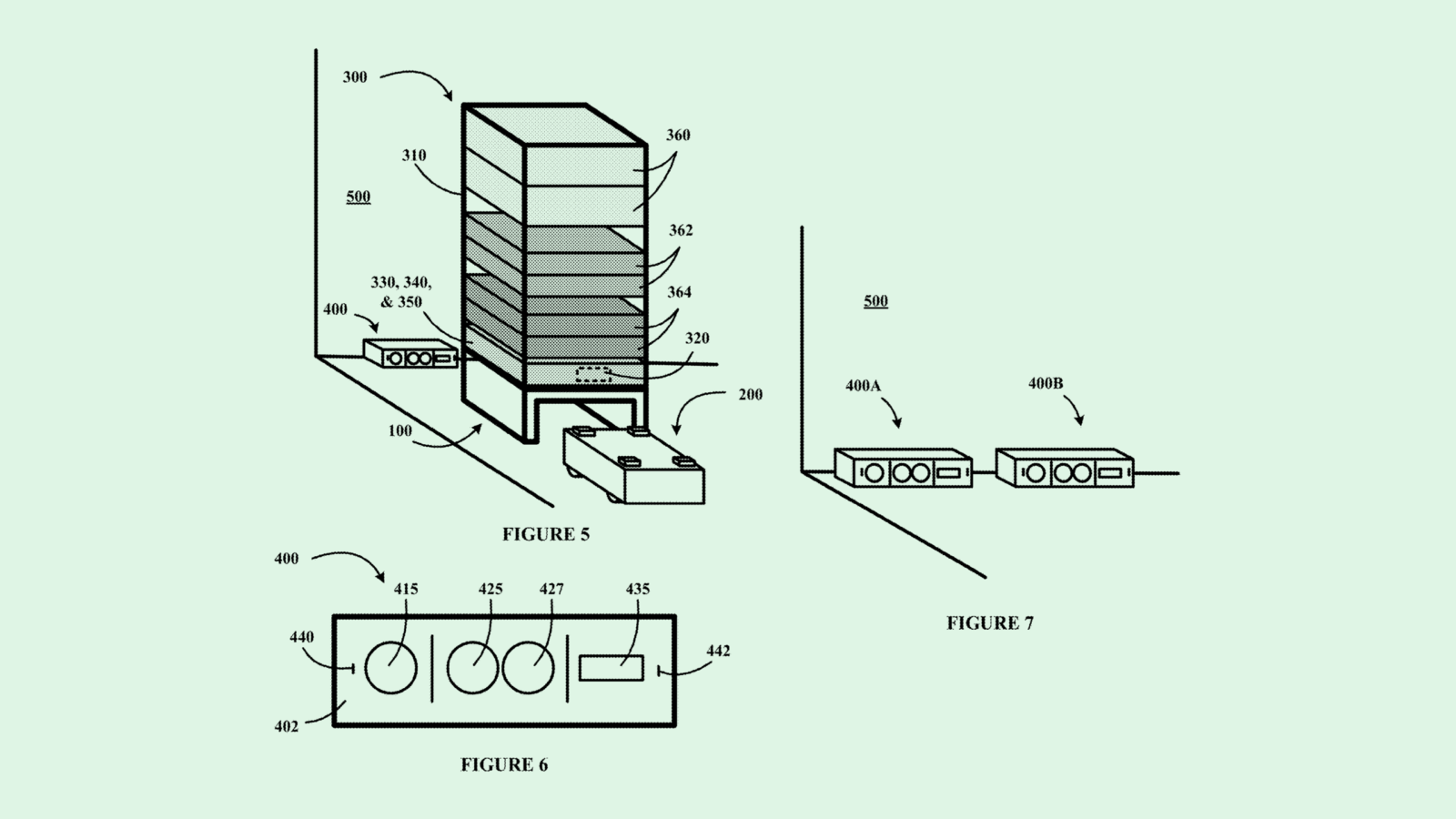

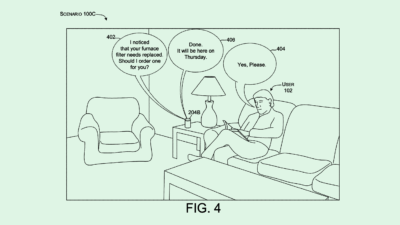

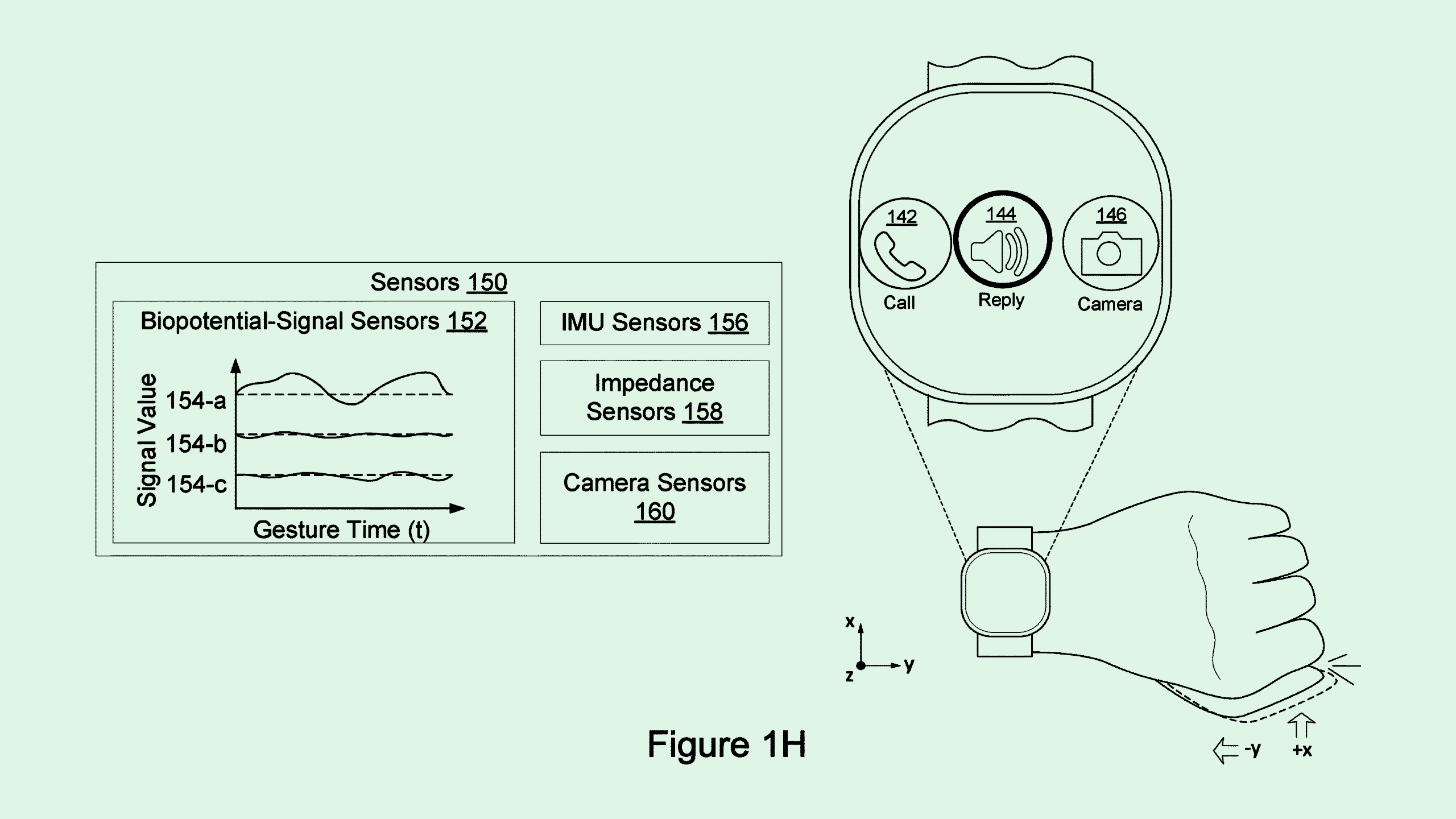

Meta’s patent details a system that uses both an artificial reality headset and a wrist-worn device, such as a smart watch, to more easily track a set of gestures used to control an AR environment.

These devices use internal sensors to track biopotential signals. While, in the patent, these are primarily referring to neuromuscular signals in the wrist, the filing noted that biopotential signals could include a wide swath of metrics, including those that read brain or heart activity.

Using these signals (rather than relying on gesture recognition via cameras on the AR devices themselves) could make interacting with these devices more efficient and intuitive.

This patent falls in line with several we’ve seen from Meta lately, such as filings for smart watch health tracking and blood pressure monitoring, as well as AR environmental control using a wrist-worn device.

It also lines up with Meta’s recent debut of Project Orion — its long-awaited “first true augmented reality glasses” — at Meta Connect in September. In the demo, these glasses were controlled with a “neural” wristband; it’s similar to what’s seen throughout its patents, but missing a screen.

“The value of that is the convenience,” said DJ Smith, co-founder and chief creative officer at The Glimpse Group. “You don’t have to hold your hand up, there’s efficiency in movements.”

However, “the bad side of it is, this is still another thing that the person has to go and attach to their body,” he added. While it aims to take away friction, it may do the opposite by creating an additional device that a consumer needs to consider, he said. “Extra hindrances” could make consumers hesitant.

While wrist-worn controllers may be the next frontier of AR technology, he said, they’re likely not the end goal. These devices are probably moving toward better sensors and tracking within the headset itself, such as the brain wave or “neural signal” tracking that we’ve seen in previous filings.

“I think it all goes back to what is the best user experience,” said Smith. “The trends are very, very clear. I’m sure that as these sensors get more popular in different use cases, their capabilities are going to continue to expand over time.”

Regulation, however, may already be preparing for that reality: Both California and Colorado have passed laws this year that classify “neural data” as protected personal information, restricting tech firms’ access and allowing customers to opt out of this data collection.