Zoom May Use AI to Tone Down Accents

Though this could be a stepping stone for live voice translation, it may come with a few ethical issues.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

Zoom wants to help you roll your R’s.

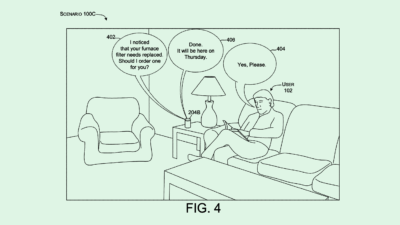

The company is seeking to patent “accent conversion” for speakers in virtual conferences. Zoom’s system uses AI to essentially translate the accent of a speaker so that it sounds “as if it was spoken by the speaker, but with a different accent.”

“The common language can sound markedly different depending on which speaker is talking,” Zoom said in the filing. “Further, different participants may have difficulty understanding the common language when it is spoken with an unfamiliar accent.”

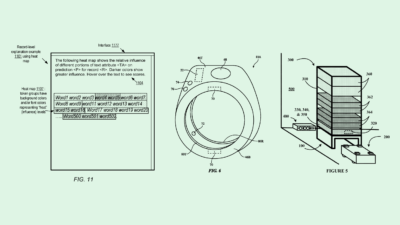

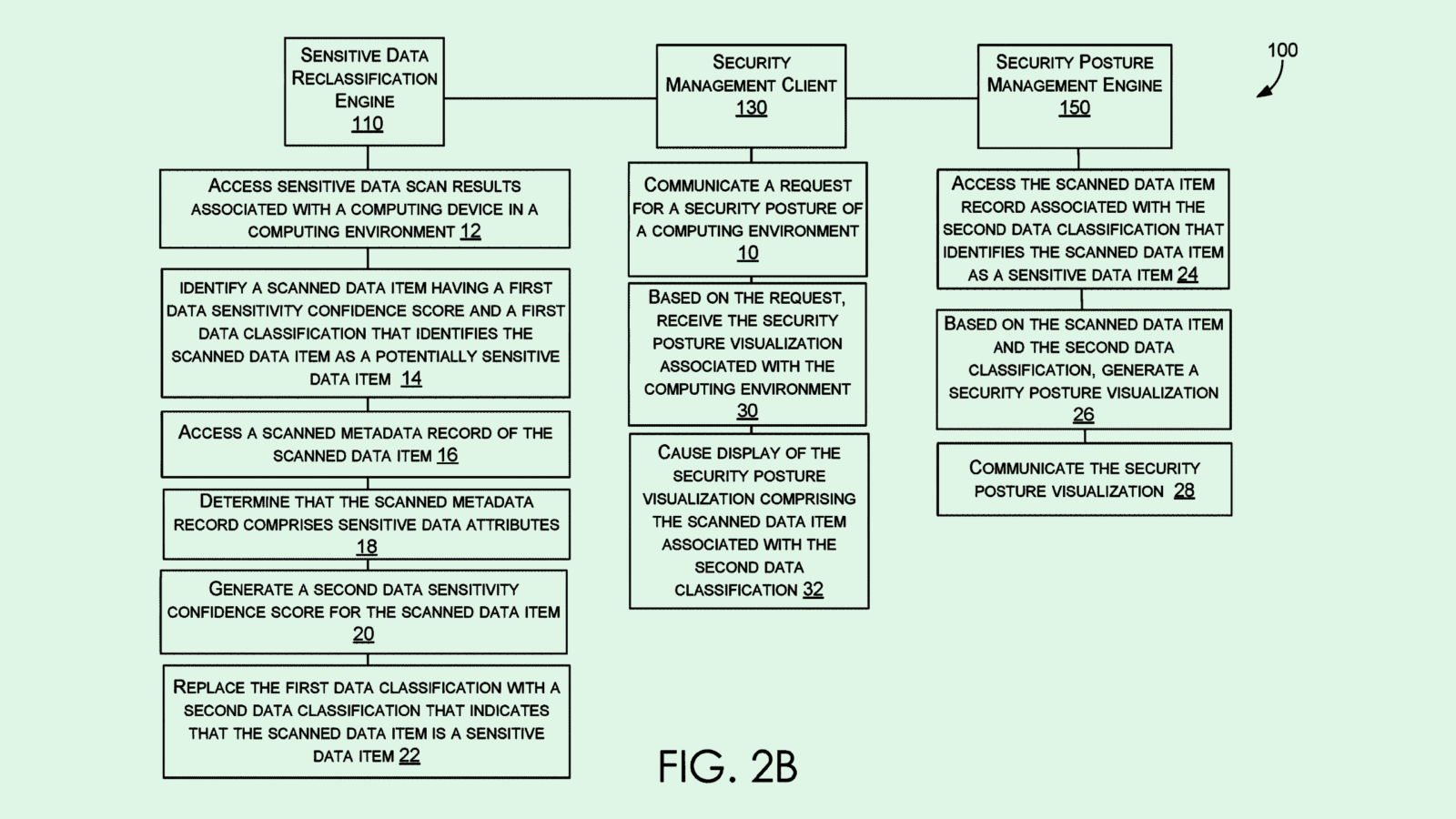

This system relies on a machine learning model trained for what Zoom calls “voice conversion.” The system collects speech samples from people with a bunch of different accents to create training datasets that represent accents from different groups or regions.

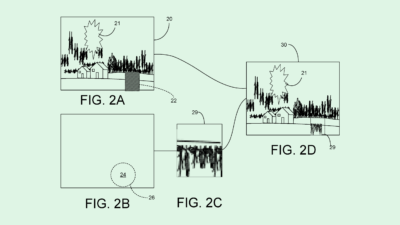

Once trained, this system takes in speech from one accent and converts it to another while maintaining both the content and the “identity characteristics of the original speaker’s voice,” such as pitch or timbre. To perform the conversion, Zoom’s model listens for speech patterns in one accent, such as different pronunciation patterns, cadences, or rhythmic patterns, and changes them to fit the accent of the native speaker of that language.

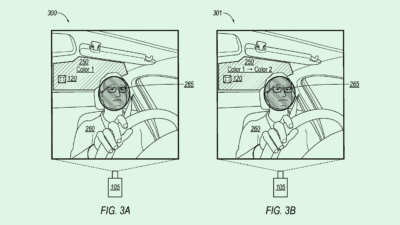

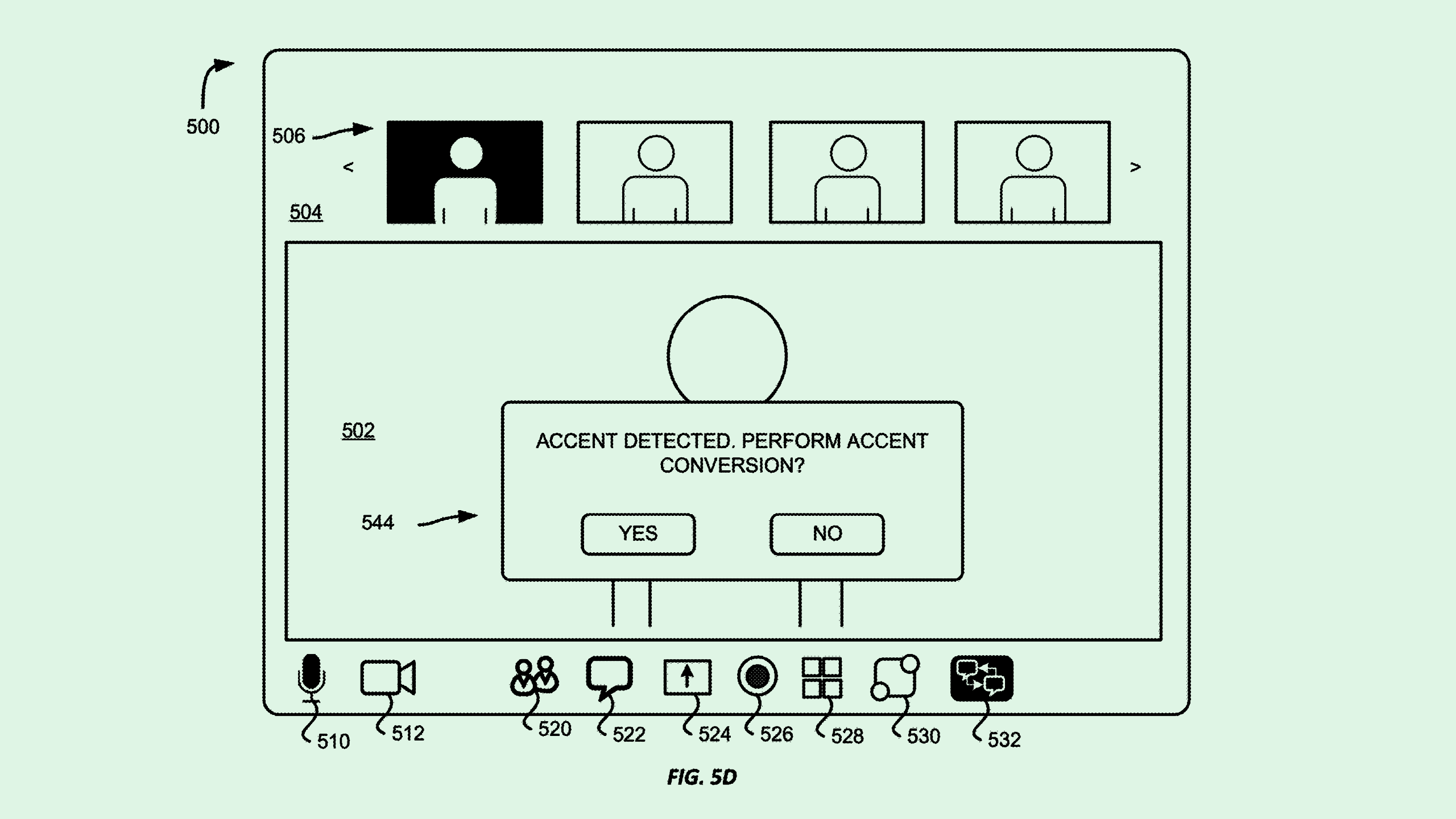

On the user end, if a participant is having trouble understanding someone in the call, they could select an option that allows their accent to be converted just for their output, which may “enable participants in a virtual conference to more easily understand each other,” Zoom said. “Multiple participants can each receive a speaker’s speech but with different accents, allowing for better collaboration.”

Though this patent seems like a well-intentioned way of easing cross-cultural communication, there are certainly ways that this tech could go awry, said Brian P. Green, director of technology ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.

For starters, depending on the language, there may be bias in how well it translates one accent versus another, said Green. For example, the company’s tech may work far better with American English than with other accents or languages due to data availability.

The source of this accent data itself may also prove to be a privacy issue. Zoom caught heat last summer for data privacy concerns over its controversial terms of service update that allowed it free rein over user data to train its AI products. The company later reversed that decision and gave users the ability to opt out after a major backlash.

But even if this tool is trained with ethical data privacy practices and is bias-free, it could still reinforce “value judgments” for certain accents, said Green.

“In some cases, having an accent does make a person more difficult to understand, but there’s also an aspect to it underlying value judgment here, which is that accents are bad,” he said. “Voice is highly connected to a person’s identity … because it’s very tied to identity, It’s kind of a sensitive topic.”

However, one positive is that this could be a stepping stone to live translation of people’s voices from one language to another, said Green. Though this patent comes with risks, he added, if it leads to people being able to overcome language barriers, it could be a “huge positive for communication.”