Twilio Makes Your Data Less Personal

Twilio wants to keep your identity out of voice data.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

Twilio wants to make sure your data is hush-hush – literally.

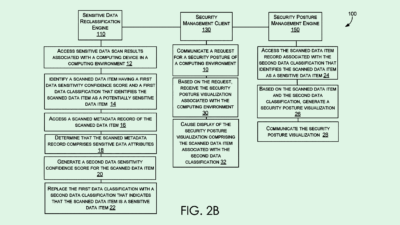

The communications tech company is seeking to patent a system for “personal information redaction and voice deidentification.” As the title implies, this tech uses the concept of data anonymization, or obfuscating customers’ identities in audio clips, to allow audio from conversations to be reviewed without sacrificing customer privacy.

“Protecting privacy of people is an important concern, so before the data is used for business or government purposes, there may be a need for the data to be anonymized to enable the use of the data without compromising privacy,” Twilio said in its filing.

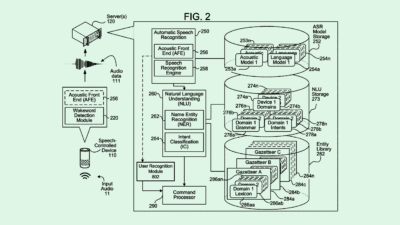

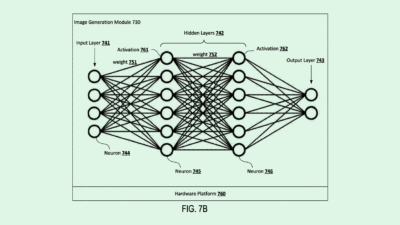

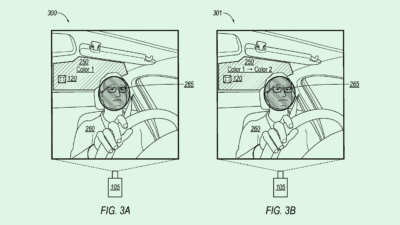

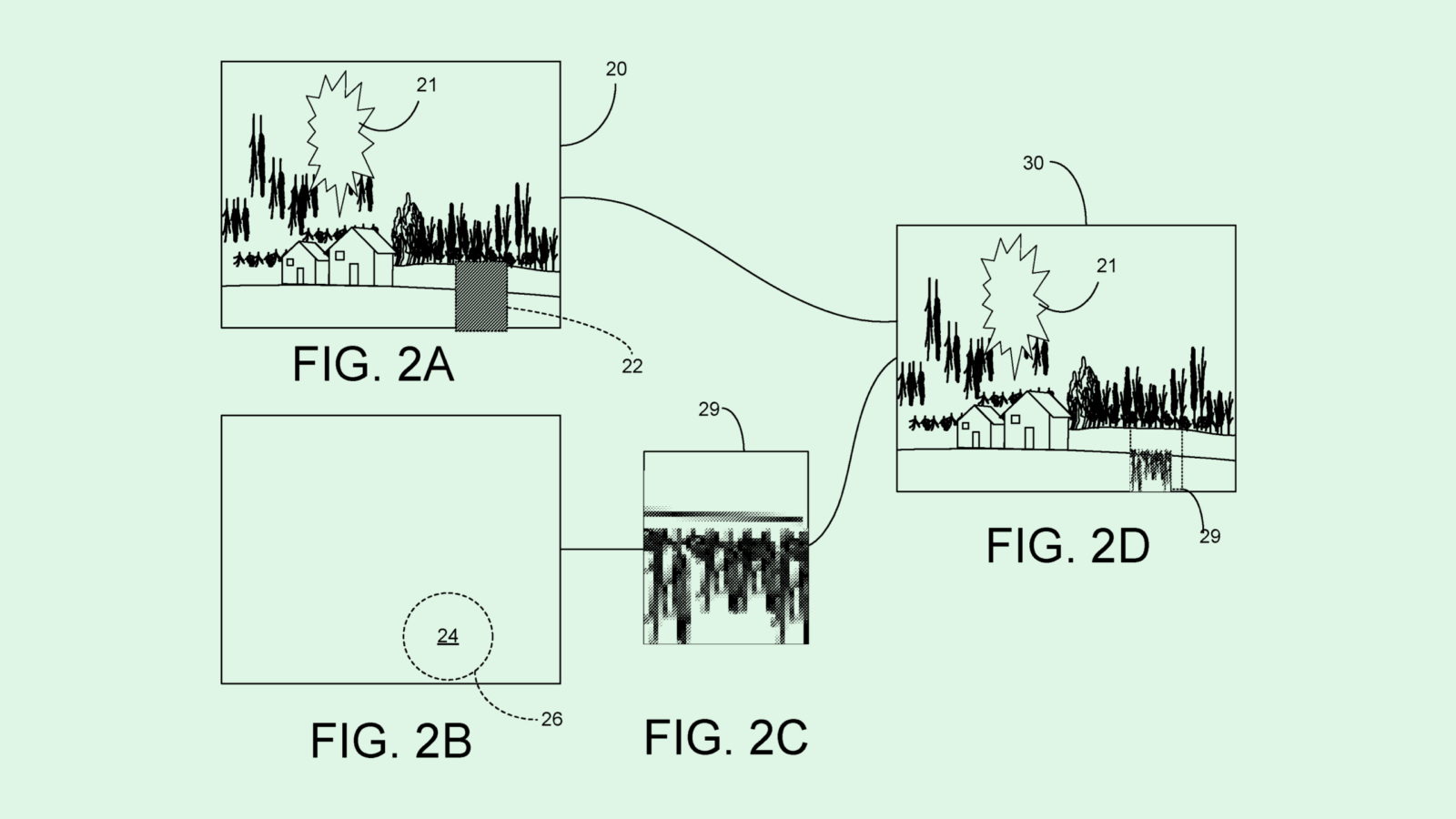

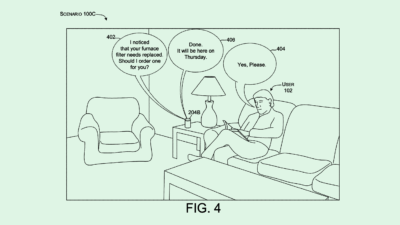

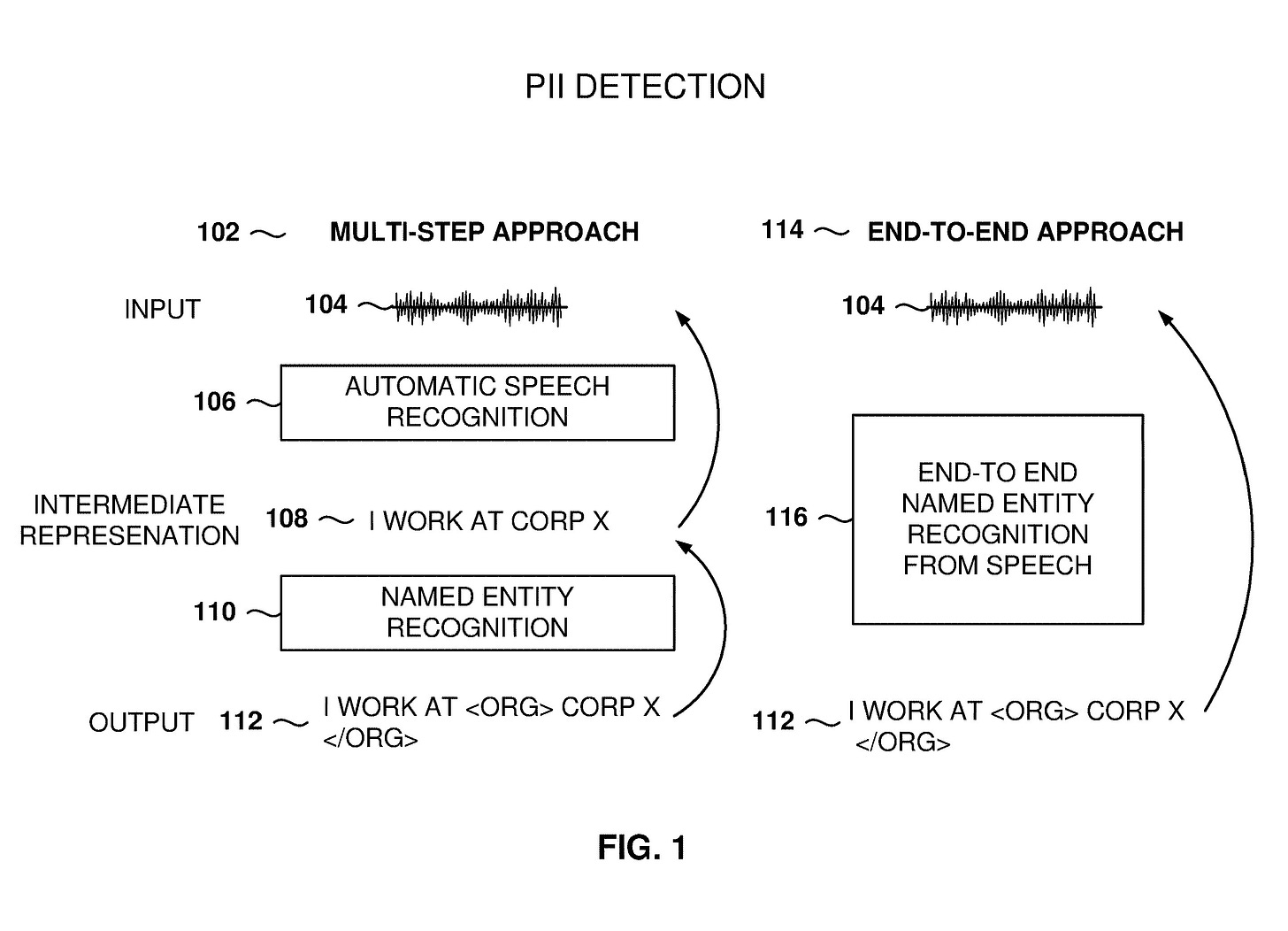

Twilio’s system works in two parts: First, it identifies and redacts any form of personally identifiable information within an audio clip. (this can be anything from a full name to an address to a social security number.) Using a machine learning algorithm trained on audio data, transcript data and redacted transcripts, the system automatically picks through audio data to obscure any personal or sensitive information in the clip and replaces it with “beeps or silence,” without a reviewer needing to analyze the transcript themselves after the fact.

Twilio’s system then takes it a step further by modifying the entire clip itself to change the voice of the customer to a “neutral voice” to avoid “the possibility that the voice of the user may be recognized.”

Along with keeping personal data safe, Twilio notes that the anonymized data could be used for a number of business solutions, including using it to train other AI algorithms without putting customer privacy at risk.

Taking a less-is-more approach is generally one of the best ways to protect customer privacy, because you can’t lose what you don’t have. Twilio seems to be taking this approach: By replacing and redacting sensitive information from its audio data altogether, the company is removing the possibility of customer exposure via security breach from the equation all together.

Data minimization, however, isn’t exactly new. Plenty of companies use this technique to cover themselves in the event of a breach. We’ve seen patents for similar tech, too: PayPal filed to patent a system to mask sensitive information in unstructured data (photos, video or audio); and Ford is seeking to patent a way to anonymize speech data by getting rid of “speaker-identifying characteristics.” While Twilio’s use case is somewhat narrow, it’s uncertain the company will be able to patent this tech, said Ali Allage, CEO and president of BlueSteel Cybersecurity.

Still, this method of cybersecurity is particularly important when it comes to audio data, as it’s especially difficult to keep safe compared to other kinds of data, said Allage. For one, because unstructured data is more difficult to store, it’s more difficult to protect.

Plus, while messaging platforms often have some form of encryption that users are made aware of, said Allage, audio-based interactions often don’t offer that same assurance. “You have an operator telling you that a call is being recorded, and then it’s capturing everything,” said Allage. “There is no encryption or decryption methodology that’s being told to the end user.”

Given that Twilio’s entire business relies on the ability for its enterprise customers – which include major companies like Lyft, Airbnb and Dell – to safely communicate, keeping their data under lock and key is crucial. But the company has had issues in the past with data security, suffering two major security breaches from the “0ktapus” hacker group last summer. Using this patent’s methods could minimize the severity if breaches occur in the future.

However, the patent leaves something to be desired in regards to ownership of information by Twilio’s customers, said Allage. While the data may be protected by Twilio, he said, the big question is “How is all this (data) stored, and who holds the keys of encryption and decryption?” he said.