My Kingdom for a Sport: Saudi Arabia Goes All in on Athletics

Why is Saudi Arabia spending a king’s ransom on sports? The Middle East powerhouse doesn’t care if you call it sportswashing.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

Sports are among the biggest revenue-generators on Earth. It’s why companies like Apple, Disney, and Amazon are shelling out a king’s ransom to obtain exclusive pro-sports broadcast rights. It’s why the Washington Commanders, one of the worst teams in the NFL, recently sold for a record $6 billion. And it’s why Saudi Arabia is quickly building a domestic athletic empire and expanding across the globe.

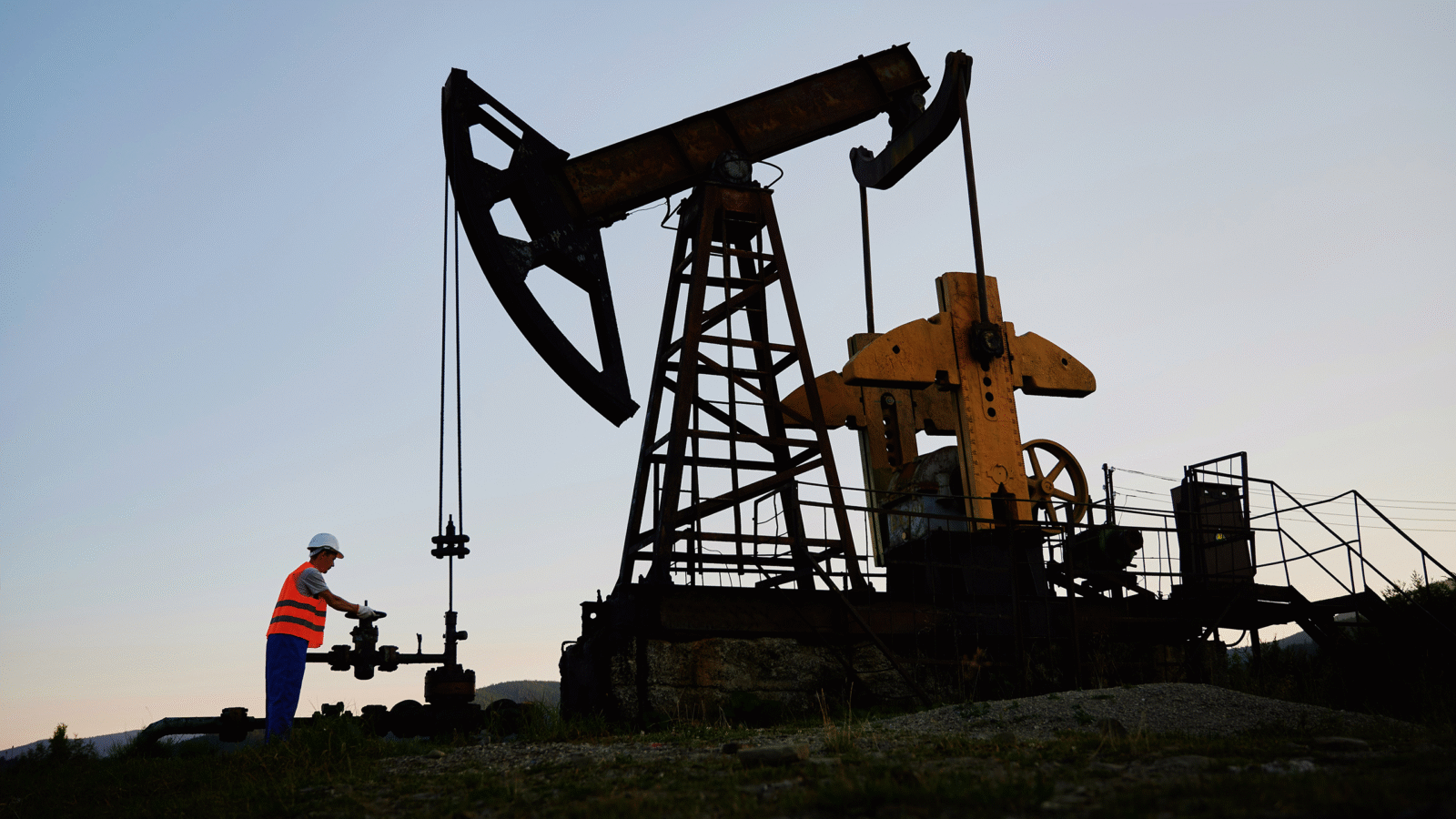

Established in 1971, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund was originally a way for the kingdom’s government to invest in all sorts of business ventures both at home and abroad — real estate, banks, transportation, cruises, retail, energy, and cars. It’s largely funded by the country’s massive oil operations and manages more than $775 billion in assets, with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman at the top of it all.

Having spent at least $6 billion across multiple sports since 2021 — that’s more than four times what it spent in the six years prior — PIF is looking to smoke the competition.

Put Me in Coach

PIF started making moves into sports soon after it formed. For many decades, those investments went toward soccer, as popular in the Middle East as it is elsewhere. In 1978, World Cup star Rivellino signed with the Al Hilal soccer team, making the Brazilian the first major player to head to Saudi Arabia. In 1992, the Gulf nation created the King Fahd Cup, a soccer tournament that was later taken over by FIFA as the Confederation Cup before being terminated in 2017.

Saudi Arabia’s biggest and splashiest sports investments have come in the last decade:

- In 2018, US-based pro wrestling powerhouse WWE penned a 10-year deal with Saudi Arabia to host pay-per-view events like Crown Jewel, the Greatest Royal Rumble, and Elimination Chamber.

- Two years later, the kingdom struck a 10-year deal with the international auto racing circuit F1 for $55 million a year to host its own Grand Prix. Shortly before that, the government-run oil company Saudi Aramco agreed to a separate 10-year sponsorship deal with F1 worth $450 million. The wealth fund even attempted to buy the whole F1 Group for $20 billion but the deal fell through.

GOOOOOOOOAL!!! Despite its multisport expansion, PIF hasn’t lost its love of soccer.

In 2021, PIF purchased a majority stake in Newcastle United FC, an English Premier League team, for more than $400 million. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s Al Nassr team signed Portuguese star Cristiano Ronaldo, one of the sport’s top and most popular players, to a two-and-a-half-year contract reportedly worth about $220 million. PIF later bought a majority stake in Al Nassr and three other of the country’s biggest clubs.

So far, the results have mostly paid off for Saudi Arabia. Attendance at its local teams’ games is down this season, but luring name-brand international stars has helped secure broadcasting rights in plenty of markets, and Newcastle FC’s progression to the UEFA Champions League in the first season following the deal likely boosted the team’s value above the purchase price, Bloomberg reported.

The biggest return on its soccer investments may be this: The country will host the FIFA World Cup in 2034. It’s not yet clear how much the kingdom will spend on hosting the event, but it’s likely to eclipse the $220 billion Qatar spent to host the tournament in 2022.

Clean Yourself Up

To critics, the mega investments in sports has an objective that goes beyond making money. Amnesty International and other groups say the kingdom is trying to change the subject from its dreadful human rights record.

The Saudi Arabian government has been known to severely limit freedom of speech, assembly, religion, and the press. Even lifestyle choices — same-sex relationships, cross-dressing, and cohabitating before marriage — can result in imprisonment, torture, or even death:

- In the past two years, Saudi border guards have allegedly bombed and killed hundreds of Ethiopian asylum seekers crossing the Yemen-Saudi border. Many of the atrocities were described in an investigation by Human Rights Watch called “They Fired on Us like Rain.”

- In the fall of 2018, Jamal Khashoggi, a columnist for The Washington Post who was often critical of Saudi Arabia and the royal family, entered the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul and was never seen again. The Saudi government tried to distance itself from Khashoggi’s death, first denying he was dead at all then later claiming he was the target of “rogue” operatives who were never given orders to kill him. But the CIA argues the assassination plot went all the way to the top and was ordered by Bin Salman.

If the Crown Prince is bothered, he’s not showing it. In an interview with Fox News last year, he said, “If sport washing is going to increase my GDP by way of 1%, then I will continue doing sport washing.”

Steven Cook of the Council on Foreign Relations said in a 2023 report that sports are just one of many investments Saudi Arabia is making as part of Vision 2030, the kingdom’s plan to diversify its economy beyond oil. “There’s something to the fact that Saudi Arabia wants to be known for something other than oil, religious extremism, and the past in which women couldn’t drive,” he wrote.

A Match Made in Match Play

Despite the criticism and attempts by many leagues and athletes to stiff arm the country, money still talks — and it was practically shouting in professional golf.

Saudi Arabia created the LIV Golf tour in 2021, the first real challenger to the US-based PGA Tour, which had somewhat of a monopoly as the most lucrative pro tour and subsequently barred their golfers from playing in LIV tournaments and barred LIV golfers from playing in PGA Tour events. LIV soon started poaching the PGA Tour’s top names — Dustin Johnson, Phil Mickelson, and Brooks Koepka to name a few — with contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars each just to join the tour, regardless of success in individual events:

- The inter-tour battle intensified with a series of suits and countersuits. In one filing, the PGA Tour accused LIV Golf of offering players “astronomical sums of money” in an attempt “to use the LIV Players and the game of golf to sportswash the recent history of Saudi atrocities.”

- But by last summer, to everyone’s surprise — including the pro golfers at the center of the rivalry — the bayonets were dropped and the olive branches extended. The two tours announced they agreed to a merger.

PGA Tour Commissioner Jay Monahan told CNBC, “Together we can have a far greater impact on this game than we can working apart.”

While that deal still needs to be finalized and could face pushback from the Federal Trade Commission, it has spurred other investments. In January, the Strategic Sports Group — a consortium of American billionaire team owners — announced it will pump $3 billion into PGA Tour Enterprise, a new for-profit entity that will oversee the circuit’s commercial properties.

Coming to America?

Saudi Arabia still hasn’t cracked popular American sports like baseball, hockey, basketball, or football… yet.

With so much money at its disposal, it’s not wild to think the PIF might want to venture onto the diamond or the gridiron sometime soon by either investing in an established professional team or creating its own league similar to LIV Golf.

“The major US sports leagues all prohibit sovereign wealth funds from purchasing majority ownership stakes in franchises,” investor and sports personality Joe Pompliano told The Daily Upside. “However, team valuations have climbed significantly over the last several years, and some of these leagues, primarily led by the NBA, now allow pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments, and other investment vehicles to own passive, minority stakes. It’ll be interesting to see how these rules change over the coming years.”

Sean Donnelly, a former lineman for the New York Giants, told The Daily Upside he understands why some athletes might be hesitant to jump ship to the Gulf nation, but he also sees it as an interesting opportunity for many sports stars if Saudi Arabia did make its own football or basketball promotion.

“I can see it happening, and it could be good for the athletes,” he said. “They would get an alternative, they can get paid better, there wouldn’t be a monopoly on their sport, and it would create more leverage against all these crazy US owners.”