Intel Patent Takes on Privacy at Eye Level

The patents highlight the data privacy issues to come with the metaverse and its headsets.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

Intel wants to keep your artificial reality experience your own business.

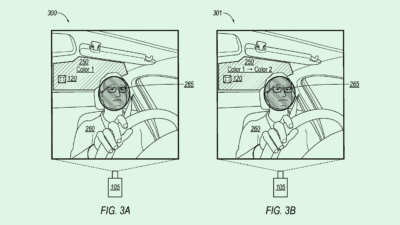

The company is seeking to patent “privacy-preserving augmented and virtual reality” relying on homomorphic encryption. Intel’s tech aims to encrypt the data that’s generated with artificial reality headsets, such as location, image data of user environments, audio data of user voices, or even biometrics like gaze or iris scans.

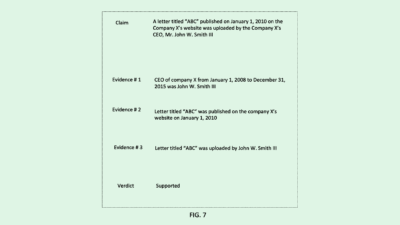

Artificial reality requires a certain degree of trust from users, Intel noted in the filing. “However, service providers can use the user’s personal data for their own purposes (e.g., sell the data or mine the data). The AR/VR applications may also be the target of cyberattacks that result in data leaks in the worst case.”

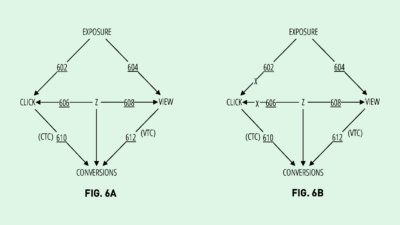

Intel’s system seeks to surpass this with homomorphic encryption, which allows the processing of encrypted data without decrypting it and revealing its content. This data is encrypted on the headset before being sent to the service provider, such as the app or program that’s running on the device.

After processing, the information is sent back to the device, where only the user can decrypt it to update their AR or VR experience accordingly. This, Intel noted, “reduces the service provider’s ability to track, spy, and target users, and reduces the risks of data leaks.”

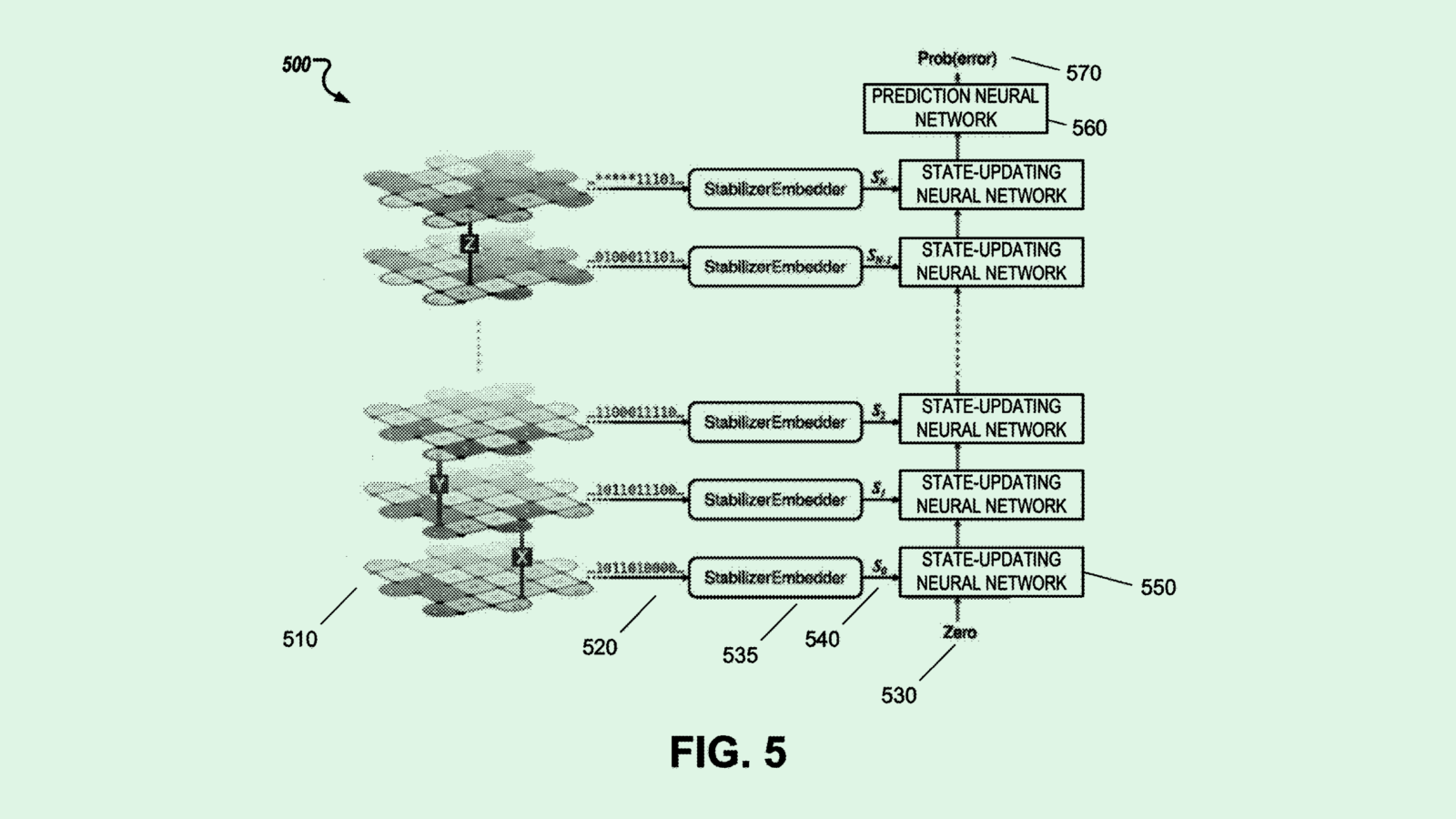

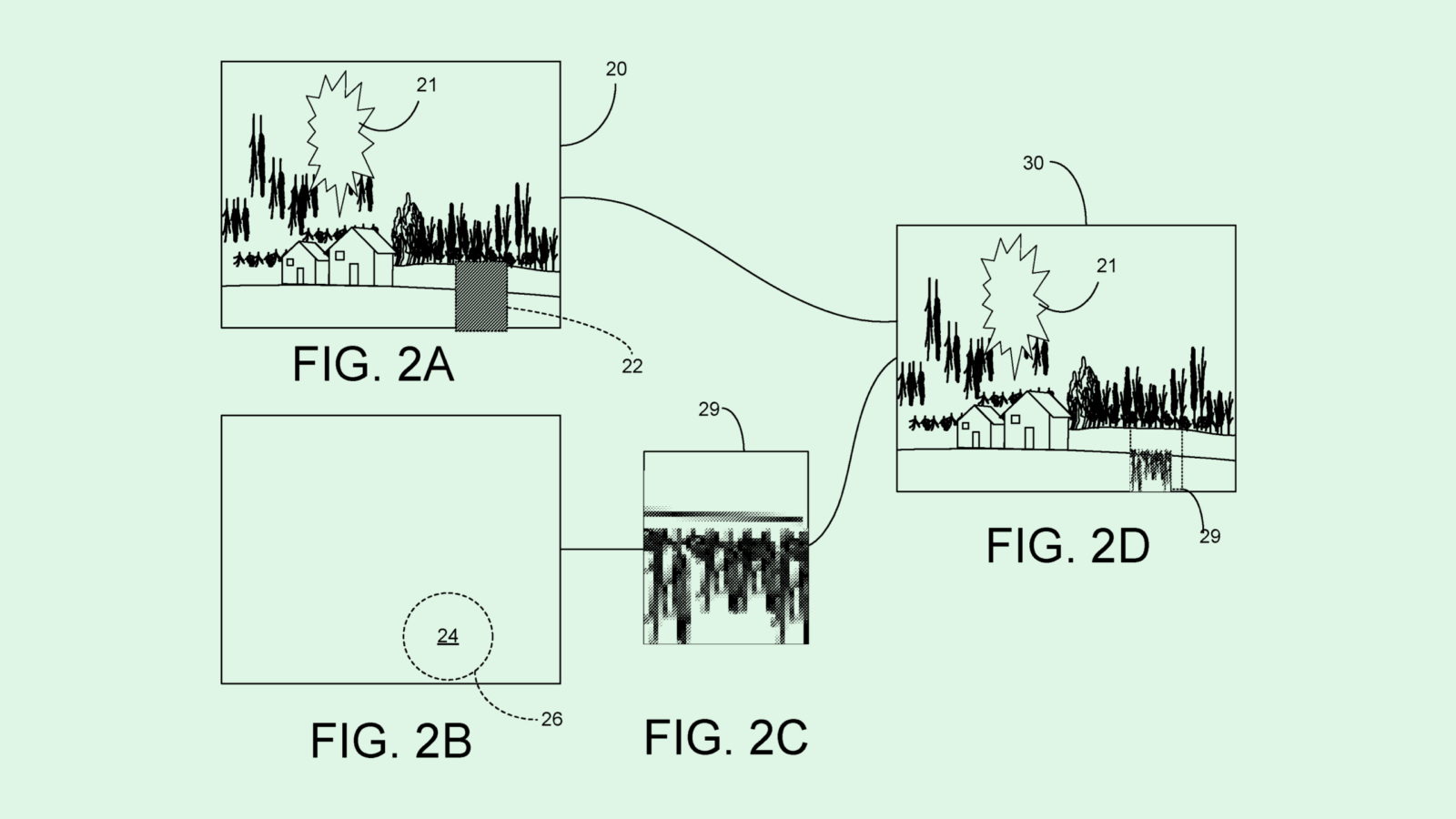

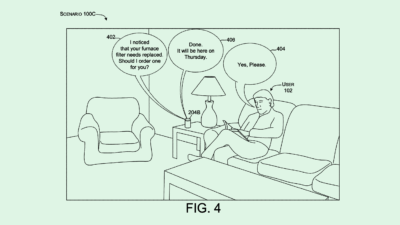

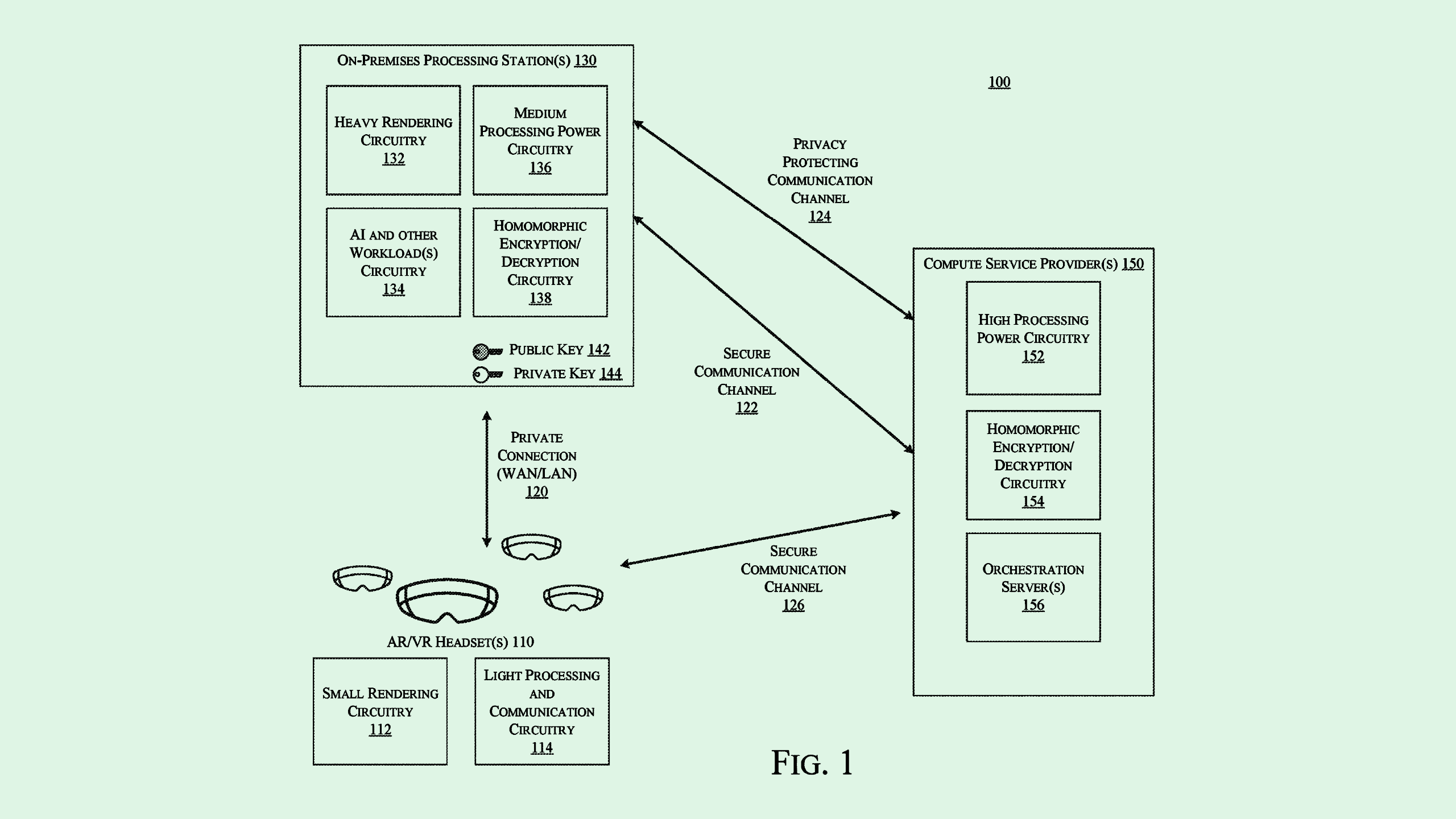

Intel’s investigation into artificial reality privacy doesn’t end there. The company also filed a patent application for “on-premises” AR and VR processing with “privacy preserving infrastructure.” This tech uses audio and video signals in a headset to identify what may be a “sensitive object,” such as speech data, biometrics, or anything personally identifiable.

If that sensitive data is needed for processing or storage on an application running on a headset, Intel’s system prioritizes processing it locally on the device itself. If the data processing is too heavy of a workload for the headset, the sensitive data is instead homomorphically encrypted before being sent to the service provider.

Intel’s patent highlights a major concern amid the growing popularity of artificial reality devices: they collect a lot of personal data, said Calli Schroeder, senior counsel and global privacy counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center.

A study from the Stanford Virtual Human Interaction Lab found that 20 minutes in VR could create almost 2 million unique impressions of a user’s body language. Because of this, privacy issues are often “built into the technology itself,” said Schroeder.

“Augmented reality and mixed reality both … have to absorb your real-world environment and sometimes that can include (personal) information,” said Schroeder. “Because you have such a high volume (of data), you’re able to draw really specific inferences from that.”

Not only do these devices present privacy issues for the wearer, but also to anyone in their periphery, Schroeder noted. If you have a roommate, live-in partner, or children, their data automatically becomes part of the scenery picked up by an augmented reality headset. Wearing one of these devices in public, meanwhile, may unwittingly subject bystanders to this data collection, Schroeder noted.

Intel’s patents may offer a solution by automatically encrypting any sensitive data before it even leaves the device – or by selectively keeping private data from leaving the device at all. And if these devices consider the identities of others to be “sensitive objects” mentioned in the filings, that provides a safeguard for those in the surrounding environment.

These privacy sticking points are even more concerning when you consider that practically every big tech company is working on extended reality in some form or fashion, Schroeder said. Meta has long been plugging away at the metaverse, Apple recently released the Vision Pro, Microsoft has the HoloLens, and Google and Samsung are partnering on an offering. “It’s really solidifying an information monopoly in a lot of cases,” Schroeder noted.

Intel, meanwhile, isn’t a force in the extended reality space, having scrapped plans for an all-in-one “merged reality” system called Project Alloy back in 2017. But patents like this could still prove lucrative, allowing it to “corner the market” on extended reality privacy while other tech companies continue to do the opposite.