Google’s Video Moderation Patent Highlights AI’s Role in Tracking ‘Objectionable’ Content

Using AI in this manner comes with its own set of risks, one expert said.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

Google wants to make sure that, between video essays and podcast clips, bad content isn’t leaking into your playlists.

The company is seeking to patent a system for identifying “videos containing objectionable content” uploaded to a social media or video-sharing service — in this case, probably YouTube. Google’s tech scans uploaded videos to decide which are “objectionable.”

“It can be difficult for a video sharing service or a social media service to detect an uploaded video that includes objectionable content and it can be difficult to detect such objectionable content quickly for potential removal from the service,” Google said in the filing.

Google’s definition of “objectionable” is somewhat wide: It encompasses “violence, pornography, objectionable language, animal abuse, and/or any other type of objectionable content.”

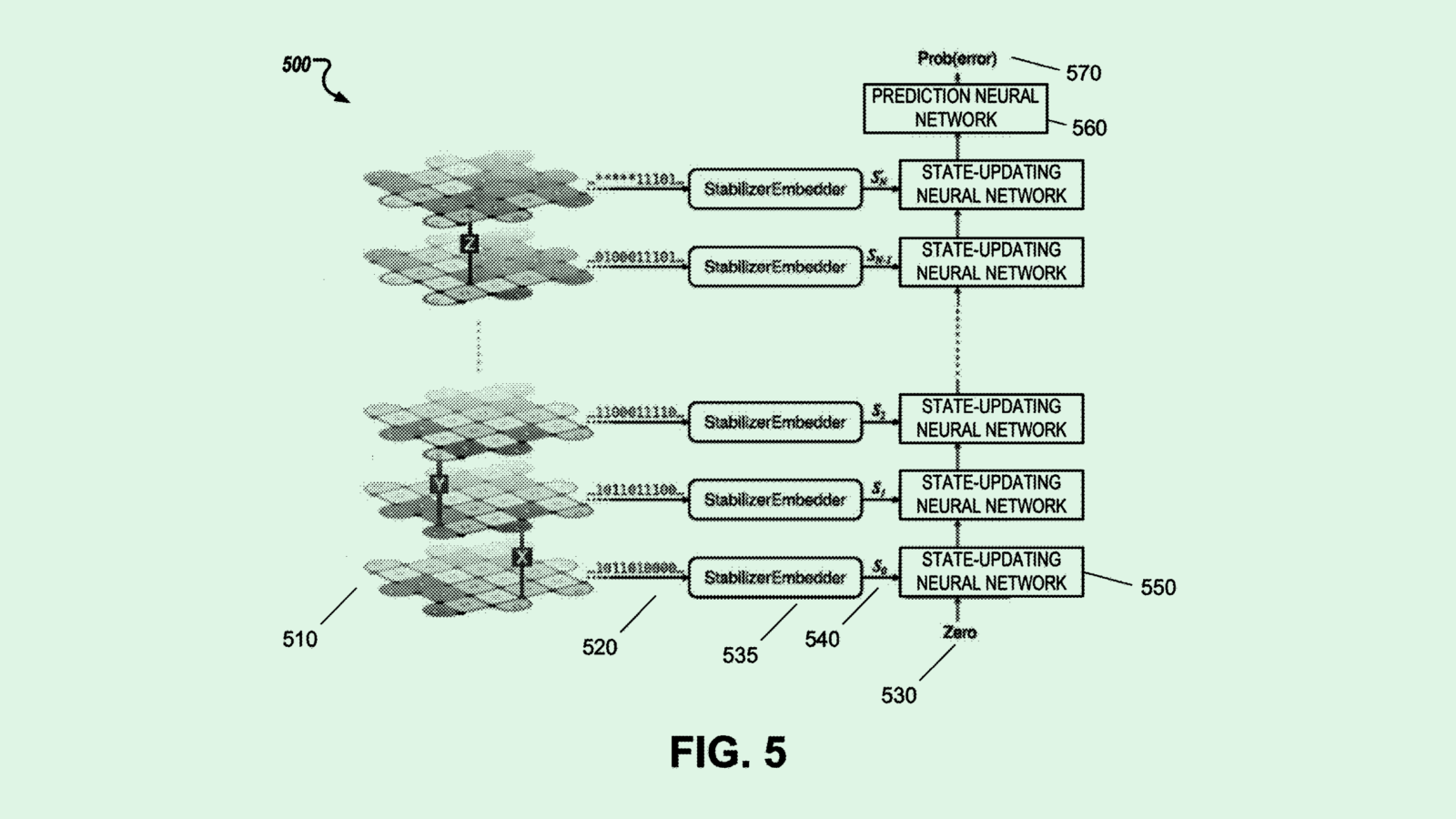

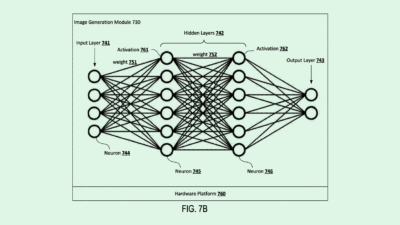

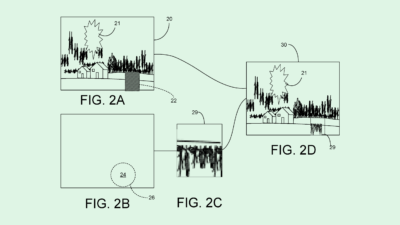

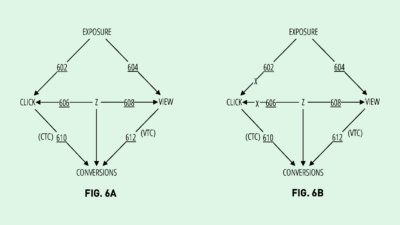

When a video is uploaded, Google’s system uses a neural network to take in its features — such as content or metadata — and create an “embedding.” To put it simply, an embedding is a numerical representation of the video’s features, which is then placed in a “multi-dimensional space,” or a highly complex graph filled with other video embeddings.

To determine if its contents are objectionable, the system compares the location of a video’s embedding within this multi-dimensional space to that of others known to contain objectionable content. The closer a video lands to other videos of that type, the more likely it is to include bad content.

Finally, if the system concludes that the video includes bad content, Google will block it from being shared.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen filings from Google that aim to mitigate the spread of so-called objectionable content. The company has filed several patent applications for spam, fake news, and abusive content detection, often involving machine learning models as part of this process.

These patents signal that tech firms see AI as a vital piece of the puzzle in tamping down whatever they deem objectionable, whether that be violence, hate speech, or misinformation, said Brian Green, director of technology ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.

“One of the great things about AI is that it does give people the ability to expand their observation of what’s going on,” said Green. “It’s not possible for human beings to watch all the content that’s uploaded to YouTube.” Stymieing the spread of this kind of content is even more important during election season, when these campaigns tend to be pushed at a higher rate.

Google’s interest in this kind of technology adds up, said Green. Along with easing the burden on content moderators themselves, effective moderating can keep the watchful eyes of regulators and the public at bay. “[Google] recognizes that if they start doing a bad job, that invites more laws, and invites legal regulation,” Green said. “That it damages their reputation.”

But using AI in this manner comes with several risks, he said. In many contexts, AI is prone to amplifying biases and hallucinating information. Google’s own AI tools have experienced this in the last several months: It had to backtrack the rollout of its AI Overview in search and is facing backlash for incorrect historical images created by its Gemini image generator.

When AI is responsible for tracking down and blocking misinformation and hate speech, Green said, this tendency may lead to false positives and negatives. And striking a balance to mitigate either can be tricky. “Very often, false positive and false negative rates or trade-offs, if you minimize one, the other tends to go up. They’ll have to figure out what the balance is.”