Patent Drop Wrapped: A Year in Review

What a year in patents from Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and more taught us.

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

It’s been quite a year in tech. We’re remembering some of the most interesting, outlandish and significant filings that Patent Drop had the pleasure to dissect this year.

AI gets emotional

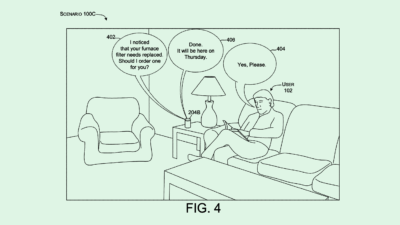

Earlier this year, we reviewed a filing from Amazon for “sentiment detection” for audio input. This system essentially trains an AI to understand the emotional tone of your voice, with the goal to “improve human-computer interactions.” The use cases included adding an emoji to a text based on your tone or recommending a certain movie or song. FYI: Amazon later announced an update to its Alexa smart speaker that makes its voice sound less robotic as well as being able to pick up on the tone and emotions in a user’s voice.

Amazon’s not the only one that looked into ways its tech could read the room. Google also sought to patent a voice assistant capable of “emotionally intelligent responses” to questions. The difference is that Google’s tech derives emotional context from the words a user says, not the way that they say them.

These patents signal a broader interest from tech companies in finding ways to integrate their tech into our lives more seamlessly. Higher adoption means higher sales, as well as more access to personal user data, which itself is highly valuable.

The next big headset

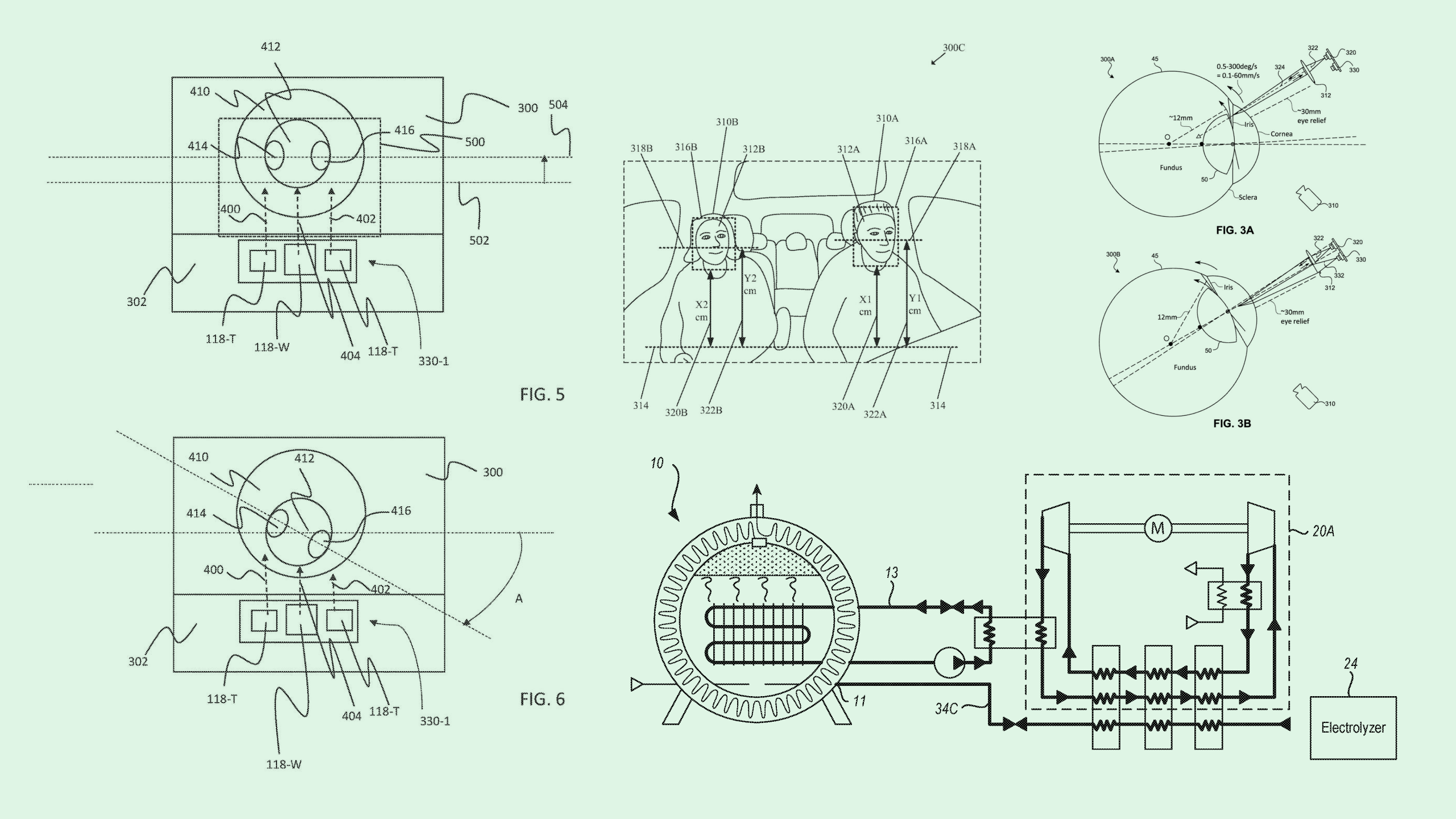

One of the biggest announcements in consumer tech this year came from Apple with the debut of its Vision Pro headset at its Worldwide Developers Conference in June. The company has sought many headset-related patents ahead of its potential February launch, including:

- Eye-tracking tech that uses “retinal reflection tracking,” which saves power by using low-power hardware in situations where advanced eye-tracking may not be needed;

- Spatial video capture and display technology, which effectively puts a user within the scene they captured;

- A digital assistant for providing “real-time social intelligence,” which actively monitors when a user is having conversations and paying attention to people in front of them.

Unsurprisingly, Meta’s patent activity included a number of patents in a similar vein, covering ways to reduce VR visual glitches while saving energy and estimate “cognitive load” by reading brain waves. Patents like these signal that tech firms are looking at ways to make headsets weigh less, track you more, and consume as little power as needed so they can stay on your face all day long.

Facing the data center problem

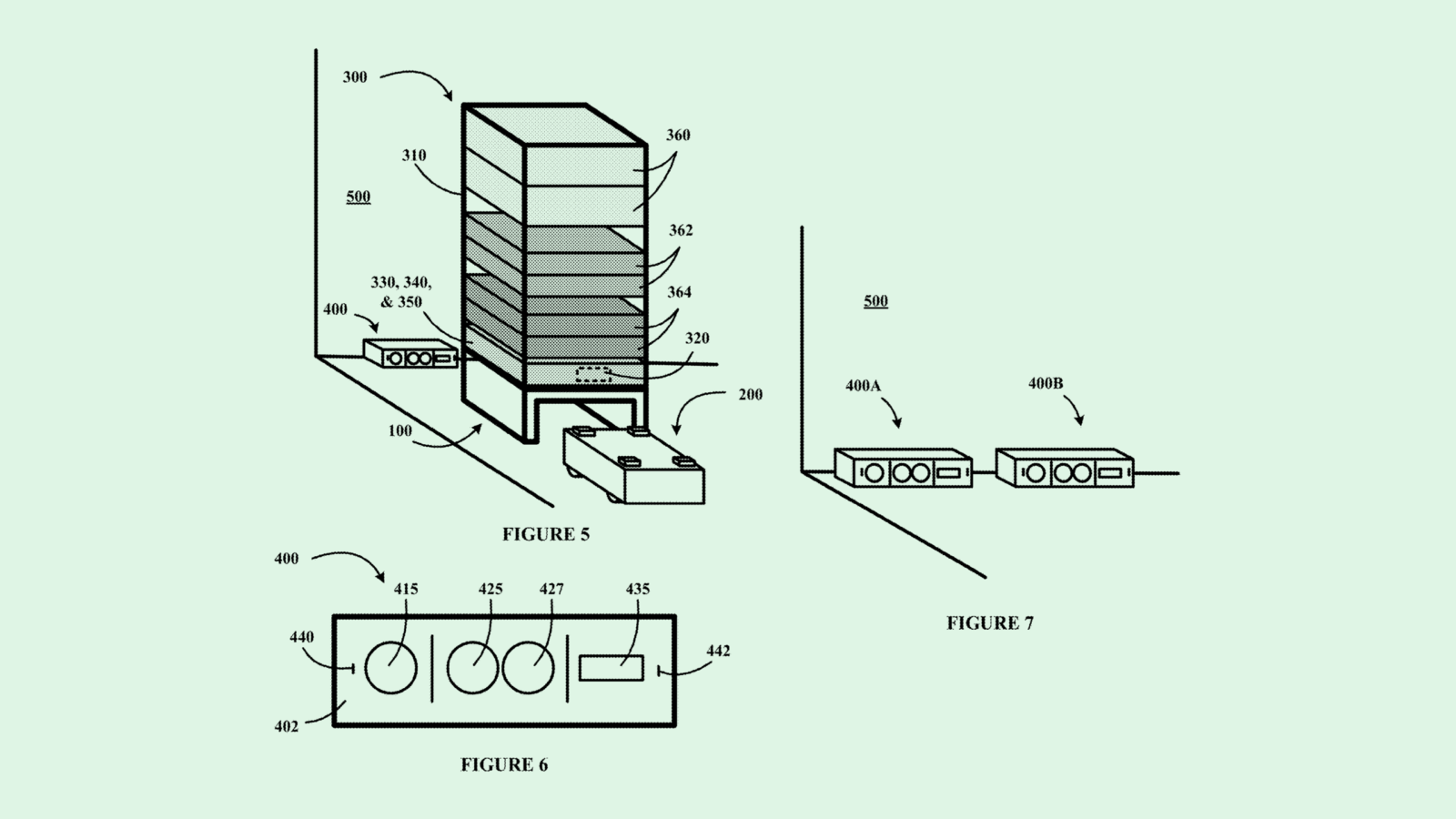

Microsoft went after a number of climate tech patents in recent months, but by far, the most offbeat of these were its cryogenic energy patents. The company sought to patent a cryogenic carbon removal patent, which essentially would use extremely low temperatures to freeze carbon solid. The patent followed another filing from the company for a carbon removal system that works in tandem with data centers.

Months later, Microsoft sought to patent “grid-interactive cryogenic energy storage” systems, which aims to store and use cryogens as an energy source to power data centers.

Microsoft has ambitious goals to go carbon-negative by 2030, but as cloud adoption grows, so does reliance on these data centers. Taken together, the company’s patent history proves its looking for a solution to data centers’ carbon footprint – and cryogenics may be part of it.

Squashing AI bias

The rapid adoption of AI has made way for a major problem: biases that emerge from improper training.

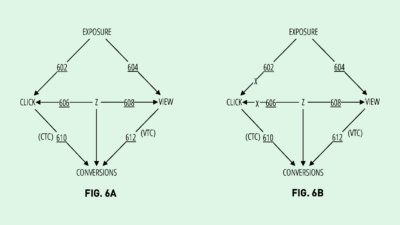

A patent from Intel aimed to combat this by recognizing “social biases” in sets of image training data. The system tackles visual biases in training data by simulating “human visual perception and implicit judgments.” Essentially, it figures out what draws a person’s eye first in an image to determine the most biased aspect of a given image or scene, then assigns that a bias score of low, medium or high.

Because a model is only as good as the data it’s trained on, having training data that doesn’t reflect human biases – whether implicit or explicit – is vital. Otherwise, those biases are replicated into predictions and recommendations, and can grow exponentially with use. And AI adoption continues, tech firms continue to look at ways to fight bias (without sacrificing speed).

Watching the electric bill

Bias isn’t the only problem with AI that the tech community wants to solve. Training AI models can be a huge power drain.

Nvidia’s patent for “task-specific machine learning operations” could help solve this problem by limiting how much training an AI model needs to get the job done. This essentially fine-tunes generic AI models for a specific task to rapidly develop “lighter, less computational intensive models.” (Both Google and Intel are working on something similar, with “parameter efficient prompt tuning” for large-scale models and “accelerated tuning of hyperparameters,” respectively.)

Meanwhile, DeepMind’s patent for a system to allocate computing resources “between model size and training data” aims to help developers only use exactly the amount of power need. This tech is basically a cost-benefit simulator for AI models, calculating the minimum amount of computation needed to get a model to work properly.

While these patents provide a few solutions to limiting power usage, they’re still merely stop-gap solutions that don’t solve the source of the problem: AI development is reliant on GPUs that suck up a lot of energy compared to CPUs.

Tech hits the road

Cars are no longer just a mode of transport – at least if Big Tech firms have anything to say about it.

Tesla, of course, is constantly looking at new ways to pack its vehicles with features. The company sought to patent a vehicle “personalization system” based on passenger location and “body portions.” This tracks user biometrics to adjust in-vehicle systems like audio output or climate control in real-time. The goal? To offer a “humanized in-vehicle experience,” Tesla noted.

Apple, meanwhile, filed a bunch of patents for its rumored Apple Car. One notable one was for a “user tracking” seat headrest, which would offer occupants personalized audio and utilize the spatial audio tech that’s built into AirPods.

Taken together, patents like these signal that the future of vehicle tech may involve a lot more in-car entertainment. But, as Tesla already has, these companies may face pushback from regulators for distracting drivers.