Special Report: How AI and Election Misinformation go Hand in Hand

“(AI) vastly increases the capacity to create any type of new media … both in speed and volume.”

Sign up to uncover the latest in emerging technology.

As the US presidential election season ramps up, fake political news has once again begun to rear its ugly head.

Political misinformation and disinformation has been an issue practically since the dawn of the printing press. Though fake news has become a hot-button topic in the last decade, the advent of generative AI, partnered with supercharged social media algorithms, may only serve to amplify the issue.

“(AI) vastly increases the capacity to create any type of new media … both in speed and volume,” said Dr. Daniel Trielli, assistant professor of media and democracy at the University of Maryland.

Patent applications reveal ways in which tech companies may be attempting to stymie this issue using the very technology that can intensify it, whether it be deepfake detection, fact-checking tools or spam scrapers. But the result may come down to AI model versus AI model.

How the Deepfake Gets Made

If you’ve used the internet at all in the past year or so, you’ve probably seen or heard at least one piece of AI-generated deepfake content. It isn’t always malicious – sometimes it’s silly and nonsensical, like the viral AI-generated videos of President Joe Biden and Barack Obama duetting “Boy’s a Liar” by Ice Spice. In those cases, it’s much easier for the average consumer to determine real from fake and figure out that Biden doesn’t have that kind of flow.

Services to create this kind of content exist everywhere, ranging from startup services to offerings from bigger tech firms like OpenAI’s DALL-E or Meta’s speech generation model Voicebox. This proliferation has effectively lowered the barrier to entry, allowing anyone with an internet connection and a few spare minutes the capability to create AI-generated fake news.

“You or I or anyone else can go generate defects at almost no cost,” said Rahul Sood, chief product officer at deepfake detection company Pindrop. “There’s no shortage of tools to use (for this) if you want a tool.”

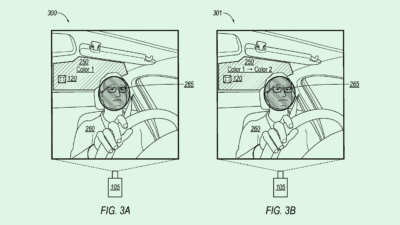

The outlandish uses of this technology still signal a dangerous possibility: It’s easy to make content that looks and sounds authentic when it isn’t. A study published last year from University College London found that participants were only able to identify deepfaked voices 73% of the time. Research also shows that, despite their confidence in doing so, people can’t reliably tell deep fake images and videos from authentic ones.

And the more data that’s publicly available from a particular figure, the more accurate the AI model can be – hence why this tech is dangerous in political contexts, said Sood. “There is enough content from politicians … that you can take any of it to generate any deep fake that you want.”

In just the past few months, a number of these situations have make headlines. In January, roughly 20,000 voters in New Hampshire received AI-generated robocalls impersonating President Biden, urging Democrats not to vote in the state’s primaries. Earlier this month, BBC reported that supporters of Donald Trump started circulating AI-created images of the former president in an attempt to garner support from Black voters. And in November, a deep fake video went viral of Florida Governor Ron Desantis saying he was dropping out of the presidential race.

“Voice is probably the most problematic of all of these,” said Zohaib Ahmed, CEO and co-founder of Resemble AI. “The reason why voice is so problematic is because we’re just not used to it. It’s going to take a while for us to educate people on that attack vector.”

Though it’s often difficult to separate the real from the fake based on the content alone, the best way to operate is to develop a healthy dose of skepticism, even for your own beliefs, so as not to simply confirm your own biases, said Trielli. “If you see an image that makes you have an instinct reaction of hate towards someone … (or) if you see something radically agree with, that’s when you should become suspicious.”

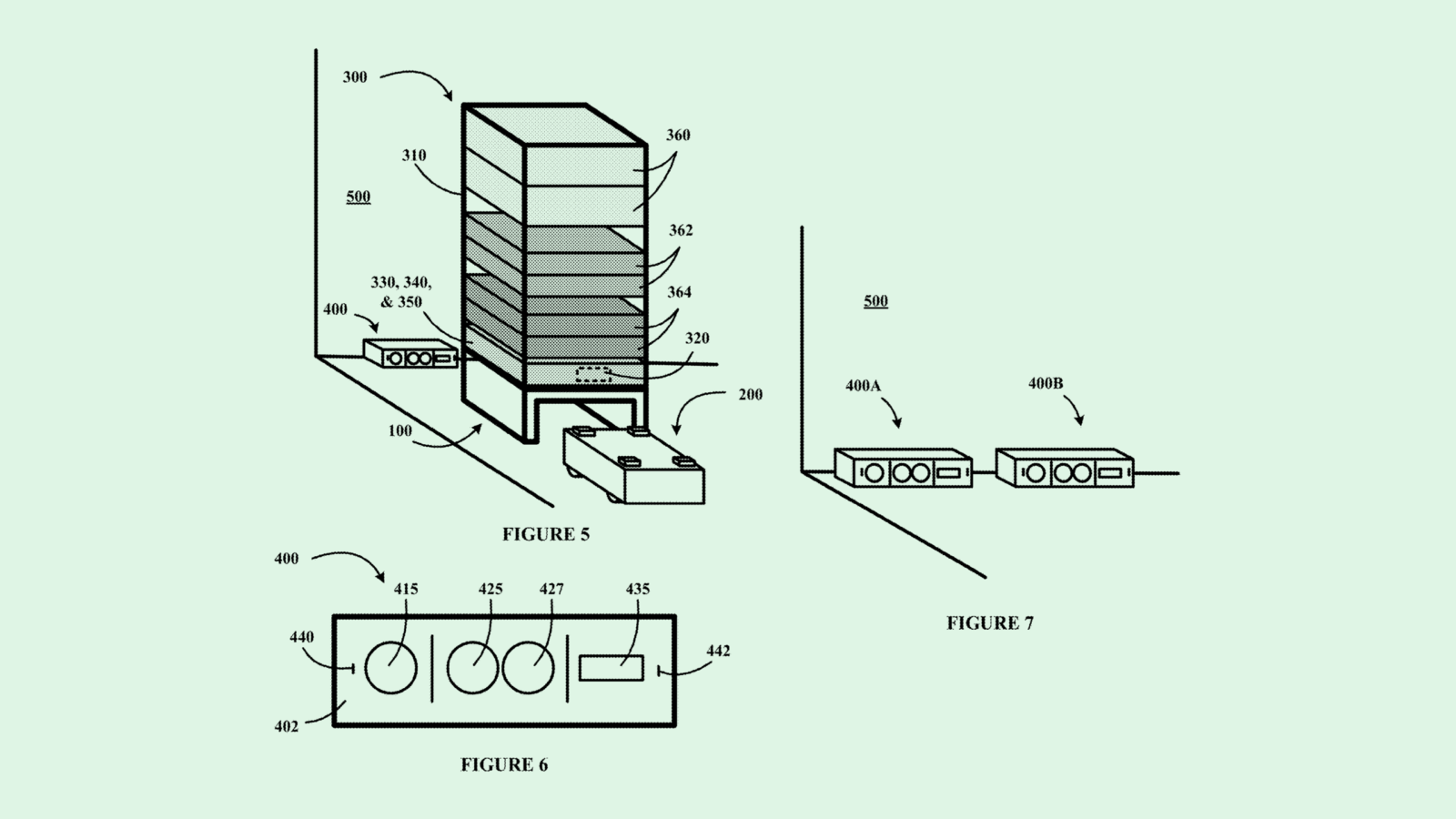

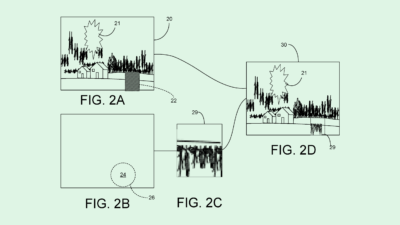

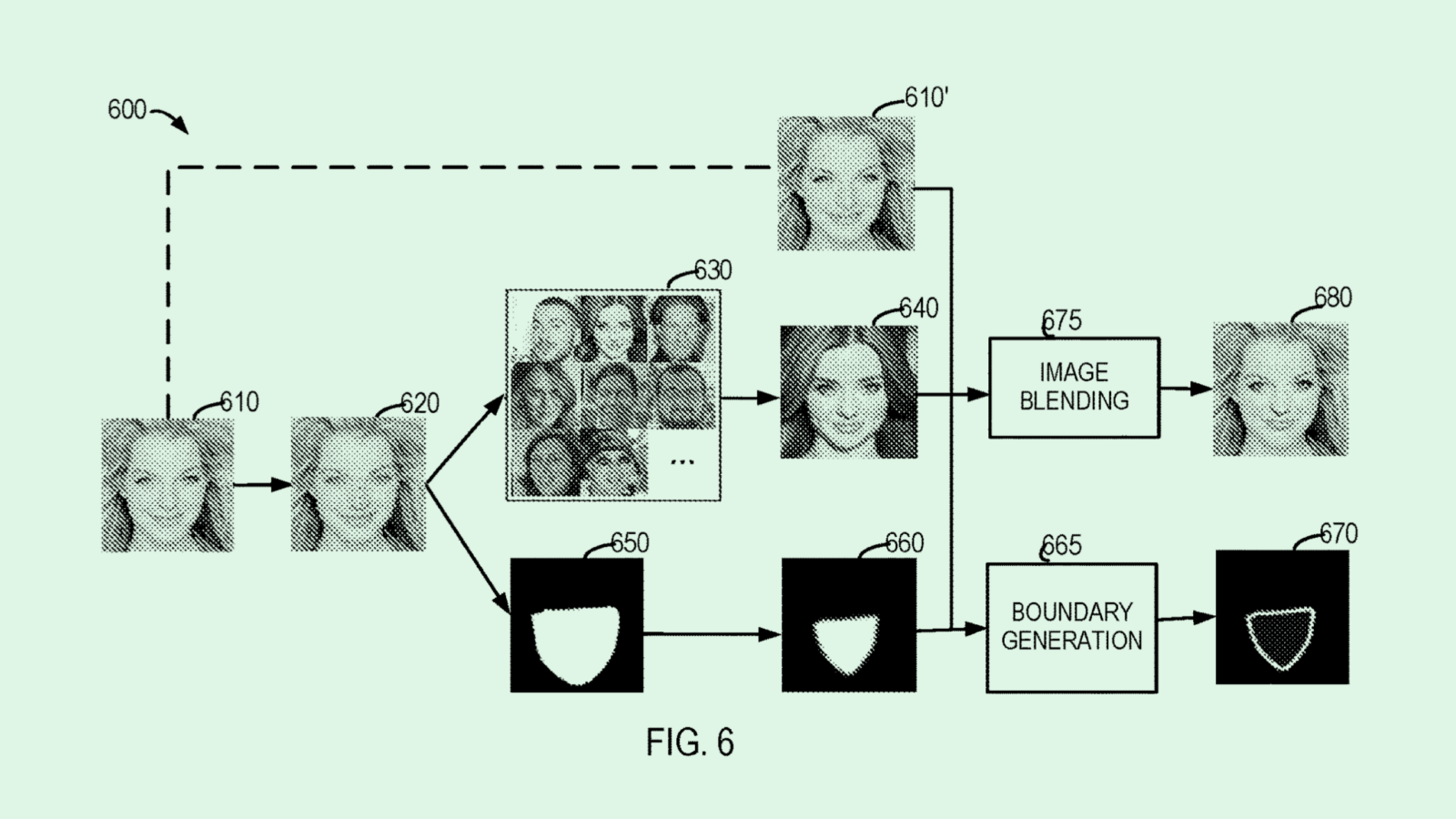

Where the human eye fails, technical solutions exist. Several tech firms have filed patent applications seeking to solve the problem of deepfake detection, many of which rely on AI themselves, including Sony’s filing to use blockchain to trace the origin of synthetic images and videos; Google’s patent for liveness detection of voice data and Microsoft’s application for forgery detection technology. Microsoft also sought to patent a solution that could keep people from creating deep fakes at all, with a generative image model that considers “content appropriateness.”

Startups are also attempting to solve this issue. Pindrop, for example, offers liveness detection as a core service. Meanwhile, Resemble AI started as a company creating AI-generated voice dupes, and has since expanded into watermarking and detecting deep fakes. “We (built) a deep fake detector because we started seeing how malicious this technology could be, even outside the scope of Resemble,” said Ahmed.

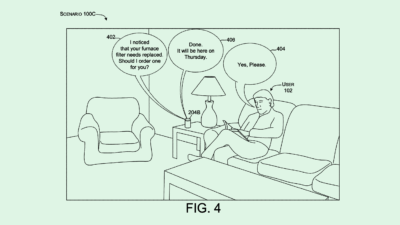

The problem of actually getting these defense mechanisms into people’s hands, however, still remains. While some forms of spam detection are already mass adopted, such as Apple’s spam call detection, a lot of these tools aren’t deployed in a seamless way for consumers yet.

Spreading the Word

Whether created for entertainment or as an actual disinformation campaign, once AI-generated content is out there, it’s not hard for it to spread like wildfire. Social media algorithms, often built on machine learning or AI themselves, reward engagement above all else. The more engaging – and often the more salacious – a piece of content is, the more viral it goes.

“Social media is designed to optimize for user engagement,” said Brian Green, director of technology ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. “If misinformation promotes user engagement, then it’s going to be promoted by the algorithms that promote user engagement.”

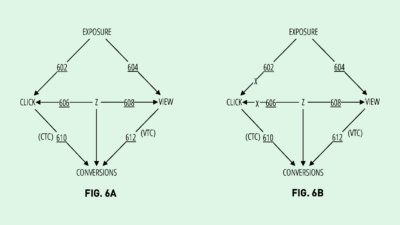

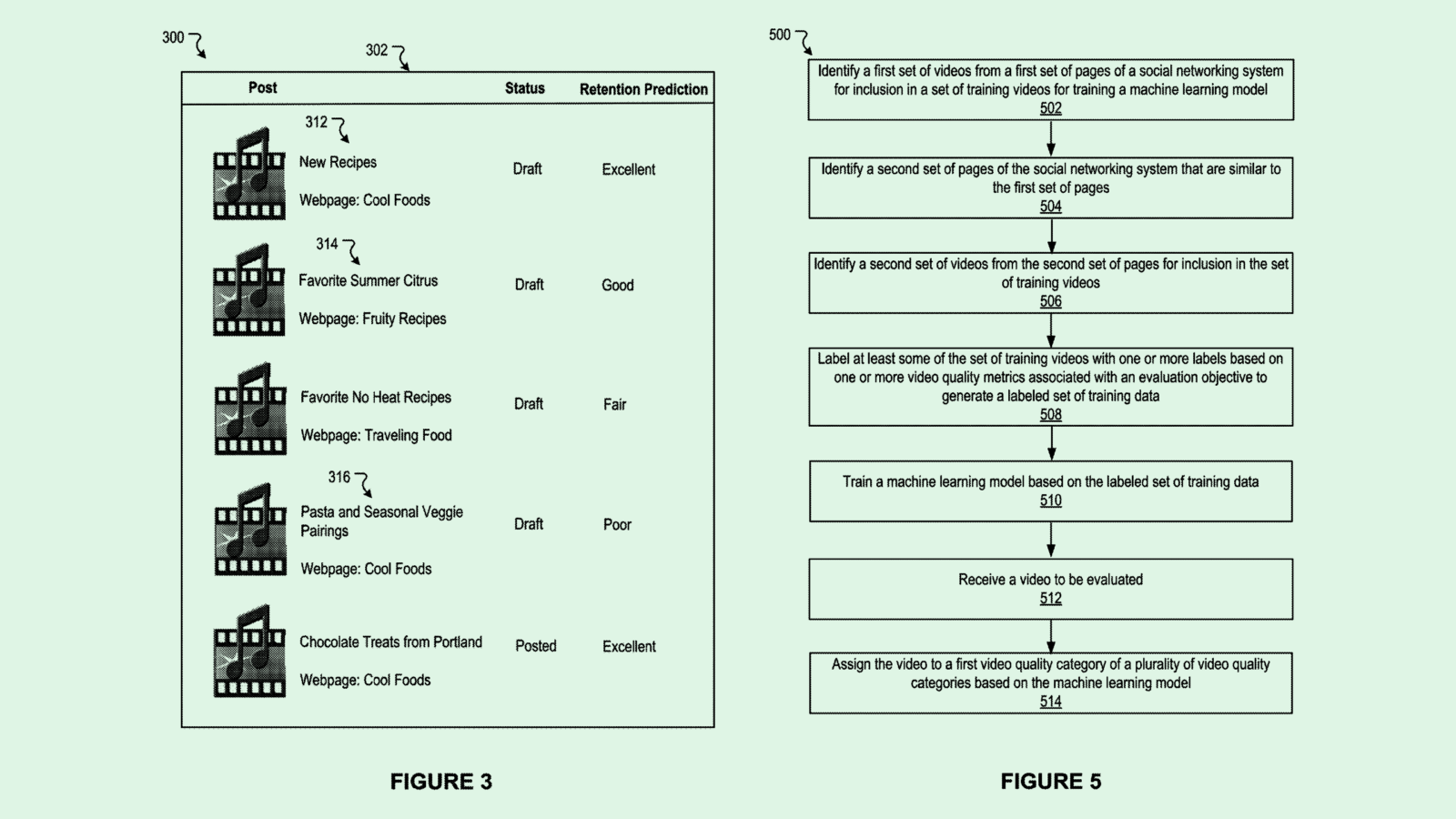

Tech firms have sought to patent several tools that aim to create and track viral content and engagement, such as Google’s tech for predicting the popularity of content; Meta’s patents for predicting video quality and ad placement based on user engagement signals; and even Microsoft’s patent for a system that can lead users down article rabbit holes based on their sentiment towards content (though this would be used in a browser, rather than a social media site).

And since more engagement leads to more advertising dollars, these firms have an obvious incentive to promote viral content, said Green. Though these companies don’t have a legal obligation to regulate misinformation, “(Social media firms) have a social obligation and cultural obligation,” Green said. “If we’re creating a future where we can’t tell what’s real and what’s fake, then we’re really endangering ourselves.”

Plus, in the US, AI-generated political misinformation doesn’t need to reach that many people to have a major effect on presidential elections, said Trielli. The way the Electoral College is set up makes it so that “tiny shifts in the electorate can decide presidential elections,” and just a few thousand voters in swing states change outcomes.

“I have a piece of disinformation that I aim to shift the election with, I don’t have to convince the majority of the people to believe that piece of misinformation,” said Trielli. “I just need a few thousand to believe it.” With AI, the volume of this kind of content and the speed at which it can spread makes that factor all the more dangerous, he noted.

To their credit, several tech firms have misinformation and AI content policies in place: X, formerly Twitter, created a policy last April that prohibits the sharing of “synthetic, manipulated, or out-of-context media that may deceive or confuse people,” and TikTok added labels in September disclosing when content is AI-generated. Meta added a similar feature to its platforms in early February in which users could disclose when video or audio is AI-generated.

Tech firms have filed several patents tackling this issue as well – many of which use AI to limit the spread. Google filed to patent tech that could detect “information operations campaigns” on social media using neural networks, as well as an application for a system to “protect against exposure” to content that violates a content policy.

Pinterest has sought to patent spam scraping technology that tracks down malicious and “undesirable content.” And while Adobe doesn’t run its own social media firm, the company sought to patent for “fact correction of natural language sentences,” which it could license out to platforms or use in its own PDF technology.

Despite these efforts, getting the problem of AI-generated misinformation under control is a matter of speed, said Green. At the end of the day, it comes down to whether the AI that’s fighting to catch fake news is faster and stronger than the algorithms promoting it and the tools creating it.

“It’s going to be an arms race,” said Green. “It’s not at all clear which side is going to come out on top.”